This month we highlight the research of Fellows from the class of 2023–24 whose projects explore how computing has reshaped thinking around everything from political power to literary study and how the promises and perils of technological advances are best measured through a humanistic lens.

Michael S. Gorham

University of Florida

Yohei Igarashi

University of Connecticut

Miriam Posner

University of California, Los Angeles

Su-Ling Yeh

National Taiwan University

Michael S. Gorham

Project: Networking Putinism: The Rhetoric of Power in the Digital Age

Michael S. Gorham is professor of Russian studies at the University of Florida. He served for 12 years as associate editor, in charge of literature and culture, at Russian Review, one of the field’s top three peer-reviewed journals internationally. Gorham is the author of two award-winning books on language, culture, and politics: After Newspeak: Language Culture and Politics in Russia from Gorbachev to Putin (Cornell University Press, 2014) and Speaking in Soviet Tongues: Language Culture and the Politics of Voice in Revolutionary Russia (Northern Illinois University Press, 2003). He has recently published articles devoted to the political and rhetorical impact of trolls, hackers, blogging bureaucrats, tweeting presidents, dictators on Instagram, Alexey Navalny on YouTube, and the rhetorical strategies of Putin propagandists in Russia’s war on Ukraine. Gorham has given numerous invited public lectures on the politics of the Russian internet and social media, served as a regular contributor to the Oxford Analytica Daily Brief on matters relating to Russian internet policy, and has given several interviews to public radio about Russian politics in general.

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions that you are considering?

Since my first book, Speaking in Soviet Tongues: Language Culture and the Politics of Voice in Revolutionary Russia, I’ve been fascinated by the way emerging political regimes, particularly during times of radical change, turn to language as a powerful tool, both communicative and symbolic, for establishing identity and authority. The closing chapters of my second book, After Newspeak: Language Culture and Politics from Gorbachev to Putin, brought my study of language and authority in Russia squarely into the age of digitally networked communication systems.

In a curious stroke of coincidence, Vladimir Putin’s now decades-long presidency has paralleled the emergence and growth of the internet and social media as key alternative modes of public communication. As loathe as Putin has been to acknowledge these new media as legitimate (dismissing them as “50% pornography” and “a project of the CIA”), he and his more web-savvy advisors have assiduously sought not only to temper their potential impact as a political disrupter, but harness them for the regime’s own communicative needs.

And so, my big questions: In a political culture such as Russia’s, which has traditionally been adversely disposed to democratic discussion and public debate (those with authority don’t speak—they act), how and to what extent has digitally mediated communication changed the public landscape of political language and given rise to an alternative “networked public sphere” (Benkler 2006)? How, at various stages of the Putin era, have the Kremlin and its online apostles sought to contain the threat of web-based political and rhetorical threats, and exploit new media to articulate, legitimate, and advance their own views and agendas? To what extent have the political language and culture of Putin and Putinism themselves influenced the discursive landscape of the Russian-language internet?

In the course of your research, have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

Although the speech registers and styles of political language in digitally networked political communication are obviously as wide-ranging as those of more traditional media, I’ve been surprised to see the emergence of a persistent style of what might be called “mediated Putinese” [need a better term!]—a markedly masculine, aggressive, and often vulgar speech register that has its origins in both informal Russian speech culture, as well as the speaking style of Vladimir Putin himself. I’ve likewise been surprised by the degree to which not only more liberal-minded political voices have lived and died by the internet in Russia, but how some of the stauncher advocates of extremely conservative, “turbo-patriotic” views have relied on digital media and developed an outsized impact on public, political discourse in Russia. (See Yevgeny Prigozhin and Evgeny Lebedev.)

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

As with my previous work, this book should underscore for scholars the integral role that language and language culture play in shaping and legitimating political authority, and encourage the pursuit of linguistically sensitive analysis of political actors, events, and systems both in and beyond Russia. I also hope my work advances our understanding of the interrelationship between new media technologies and the legitimation of political power, particularly in authoritarian regimes. Finally, my examination of oppositional politician Alexey Navalny’s reliance on, and mastery of, social media to establish his position as a potent critic and alternative to Putinism, should provide a foundation for further investigation of his remarkable and tragic political career.

Yohei Igarashi

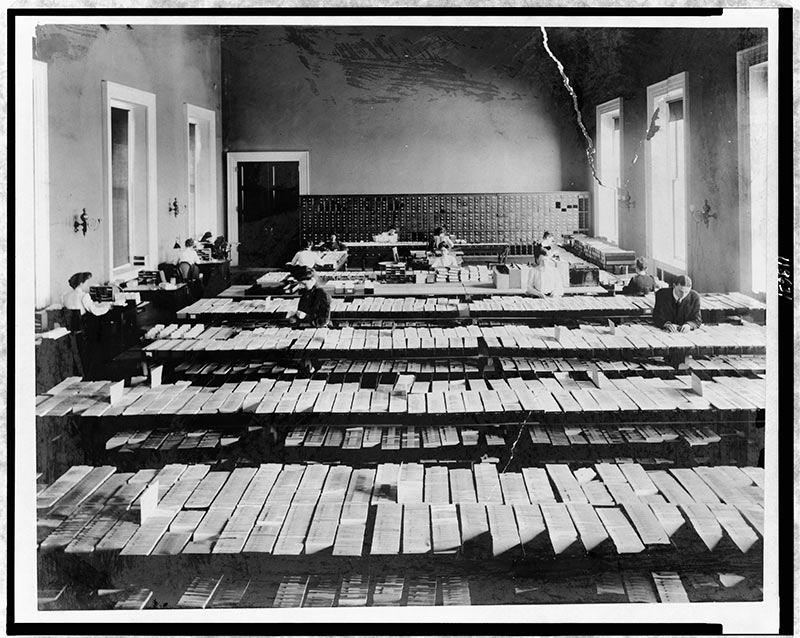

Project: Word Count: Literary Study and Data Analysis, 1875–1965

Yohei Igarashi is associate professor of English at the University of Connecticut. His research focuses on two fields: British romantic literature and computational literary studies, past and present. His work on British Romantic literature draws on media studies, the history of communication, and sociology, and includes The Connected Condition: British Romanticism and the Dream of Communication (Stanford University Press, 2020), an essay in Studies in Romanticism which won the Keats-Shelley Association of America essay prize, and other publications. In the field of computational literary studies, he has published collaborative articles and papers on topics ranging from poetic form to plain writing, as well as a recent magazine piece in Aeon on computer-generated writing. Igarashi is currently working on the history of the relationship between academic literary study in the US and computing, a part of which has been published in New Literary History. His wider interests include the histories of reading, writing, rhetoric, and literary criticism.

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions that you are considering?

I was initially interested, about ten years ago, when there were more intense discussions in literary studies about distant reading’s challenge to close reading, in the history of the relationship between those two practices. So I wrote an article, “Statistical Analysis at the Birth of Close Reading” (2015), and, as I worked on and finished a book on Romantic poetry and the problem of communication, I continued to think about the relationship between literary study and computing.

In the course of your research have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

There are little surprises all the time in doing research, and one of them has been how at different points from the late 19th century and through the 20th century, literary scholars called for empirical, quantitative, and supposedly more objective ways of studying literature—of analyzing literature scientifically. They’re each differently inflected by their different historical moments, but some of them are also surprisingly repetitive, similar to one another in rhetoric and rationale. And these proposals are largely ignored or rejected each time. So this, along with what this history might mean for today’s computational literary studies, are things I’m trying to account for.

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

One of the questions my project takes up, and which I think would be an interesting avenue of inquiry in general, is what it means to treat artworks, textual or other, as data. It’s a complicated question that has to have many considerations—the philosophy of art, aesthetics, the specificities of the medium in question, theories of datafication, and more—and while I think I can make a contribution, providing one way of thinking about the datafication of verbal art, it’s a larger issue that I would like to see answered by others too.

Miriam Posner

Project: Seeing Like a Supply Chain: The Hidden Life of Logistics

Miriam Posner is assistant professor at the University of California, Los Angeles Department of Information Studies. She is also a digital humanities scholar with interests in labor, race, feminism, and the history and philosophy of data. Her PhD, in film studies and American studies, is from Yale University. She has published widely on technology, data, and the humanities, including pieces in Logic, The Guardian, and The New Yorker. At the National Humanities Center, Miriam is at work on a book about the technology of global supply chains, under contract with Yale University Press.

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions that you are considering?

Some years ago, brainstorming assignments for an undergrad course on digital labor, I thought of asking students to trace the supply chain of an electronic device. Luckily, I had the sense to attempt the assignment myself, and I quickly learned that it’s a nearly impossible task. Not only do companies keep their supply chains secret, but often, they don’t actually understand their own supply chains. That’s because these global networks are massively improvisational and fast-moving. If one node of the supply chain drops out, no one, except its nearest neighbors, is necessarily aware of a substitution. This insight—that companies can time the arrival of a product down to the hour but remain ignorant of the conditions of its production—was the spark that initiated this project.

In the course of your research have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

At one industry meeting, a supply-chain management veteran leaned into the mic: “The dirty secret of supply-chain management,” he intoned, “is that no one ever knows where the hell anything is.” I’ve been shocked at the extent to which this is true—not always, and not for everyone, but in general, it’s very hard to know where products or components are at any given point in time. No matter how seamless an online purchase experience, the product’s procurement is likely a cacophonous tangle of subcontractors, freight forwarders, drayage companies, and trucking brokers. There’s no eye in the sky coordinating it all—just countless person-to-person connections, everyone scrambling to get your shower curtain or printer cartridge to your door on the right day.

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

I’ve found it really eye-opening to know the ins and outs of the profession of supply-chain management. I had the idea that the industry is much more closely coordinated and centralized than the chaotic tangle it actually is. And supply-chain management, of course, is a huge part of global capitalism, so anyone who wants to understand what actually comprises the “global economy” will be interested in the logistical mechanics. I think people will be interested, too, in where power lies in the network of supply-chain relationships. I thought that the companies commissioning products would be calling the shots. In fact, though, companies called freight forwarders, which book spaces on cargo ships, hold a lot of the cards, since they’re the ones with data about which products are where.

Su-Ling Yeh

Project: Enhancing Well-Being in the Age of AI: How Psychology Can Help

Su-Ling Yeh holds the Fu Ssu-nien Memorial Chair at National Taiwan University and the distinguished position of lifetime professor in the Department of Psychology. With a rich background in interdisciplinary research, she also serves as the associate director at the Center for Artificial Intelligence and Advanced Robotics. Her extensive research interests encompass a wide range of fields in psychology, including consciousness, perception, attention, multisensory integration, aging, and applied psychological research. She has been honored with the Academic Award from the Ministry of Education and the Distinguished Research Award from the National Science and Technology Council of Taiwan. Her ongoing research is dedicated to investigating how psychology can contribute to enhancing human well-being in the era of AI, with a strong emphasis on aligning with human needs and emphasizing the uniqueness of human beings.

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions that you are considering?

The initial spark that ignited my interest in this project arose during my fellowship at Stanford University’s Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences. As I delved into the origins and development of AI, along with the history of psychology, intriguing parallels emerged. These parallels prompted profound questions: What distinguishes human nature from AI? How can psychology, with its pursuit of well-being, fulfill human needs in this context? This project aims to unravel these questions by exploring the unique dimensions of human experience and leveraging psychological insights to enhance well-being in the age of AI. By integrating historical foundations, interdisciplinary collaborations, and an understanding of human beings, this research endeavors to shed light on aspects of humanity beyond replication by artificial systems. Ultimately, the goal is to navigate the complexities of the AI era and cultivate a future where human well-being remains paramount.

In the course of your research have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

During my research, I found the striking similarities between Turing’s exploration of machine thinking and behaviorism in psychology, as well as the convergence of explainable AI and the cognitive revolution, underscore the interconnectedness of these fields. Additionally, the impressive capabilities exhibited by ChatGPT and GPT4, such as zero-shot learning and a theory of mind, highlight the potential for AI systems to generalize, infer, and comprehend others’ thoughts. These revelations underscore the need for ongoing exploration and collaboration between AI and psychology, fostering intriguing inquiries into the convergence of cognitive science and the ethical implications of AI systems with human-like cognitive abilities. They act as catalysts for further investigation into the captivating possibilities that emerge at the intersection of AI and psychology.

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

In the context of the aging population, this project explores the convergence of AI and psychology, uncovering new avenues of inquiry. Understanding the development trends and implications of AI, psychology provides insights into its capabilities, limitations, and potential for addressing the needs of older adults. This research investigates ethical considerations, AI-driven interventions for well-being, and the impact of AI on decision-making in eldercare. Fostering AI for well-being, the project facilitates collaborations and develops AI technologies aligned with the unique needs of older adults. Ultimately, it leverages AI advancements in psychology to enhance their well-being and advance psychological research and practice in an aging society.