In this issue we highlight the research of Fellows from the class of 2021–22 who are exploring the ways that we “hear” the world around us—bodily in our daily lives, in a concert hall, or through expressive movement—simultaneously constructing a sense of ourselves and the community in which we belong.

Jacob M. Baum

Associate Professor of History, Texas Tech University

Mark Evan Bonds

Cary C. Boshamer Distinguished Professor of Music, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Ana Paula Höfling

Associate Professor of Dance, University of North Carolina at Greensboro

Jacob M. Baum

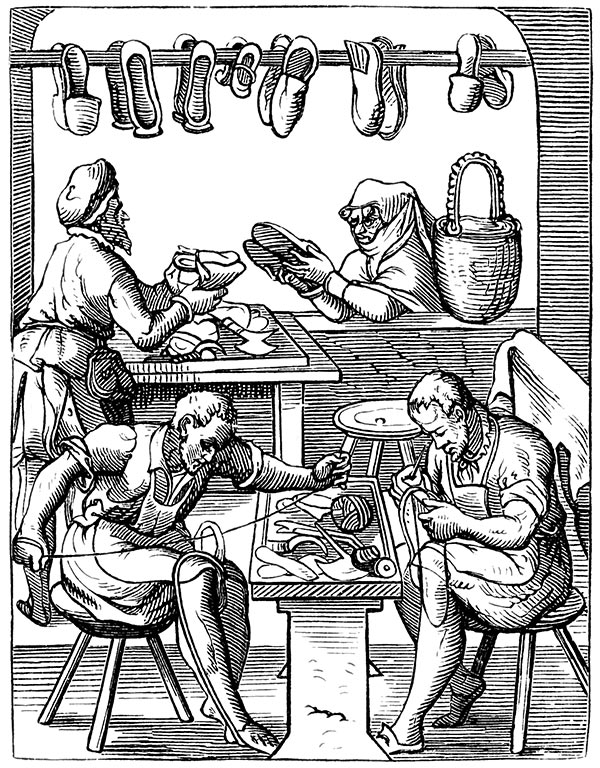

Project: The Deaf Shoemaker: Ability, Disability, and Daily Life in the Sixteenth Century

Jacob M. Baum is associate professor of history at Texas Tech University. He researches late medieval and early modern European history, with particular focus on the German-speaking world. He is especially interested in how religious and scientific ideas, typically considered the preserve of elite intellectual spheres, intersected with and exerted force in daily life and popular culture. Baum’s current research focuses on histories of physical impairment and disability in the early modern era, with particular emphasis on how religious, scientific, and social forces shaped the experience of deafness and blindness in Europe between 1400 and 1750.

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions that you are considering?

I initially came to Sebastian Fischer’s notebook when I was in the final stages of drafting my previous monograph, Reformation of the Senses. At the time, I noted that he was adventitiously deaf, though couldn’t really address this within the framework of that study. Fischer nonetheless prompted me to reflect on how little the field of sensory studies has dealt with sensory impairment, despite this being suggested in some of the earliest, foundational documents in the field. From there, I pivoted into disability and deaf studies and realized how little work has been done for the period before the eighteenth century. I realized that Sebastian Fischer’s notebook, therefore, represented a unique opportunity to consider how disability was understood and experienced before the modern age.

In the course of your research have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

When I first looked at the original manuscript of Fischer’s notebook, I was quite surprised, and then fascinated, by the quantity and quality of illustrations the shoemaker added to his text. They cover a wide range of subjects, from well-known buildings to a collection of sketches of subjects who lived with embodied differences of their own. This collection, in particular, caught my attention: it included conjoined twins and other subjects who would have at the time been identified as ‘monstrous births.’ Complementing these sketches were Fischer’s reflections on the lives of the subjects. In contrast to the sensationalism one often finds accompanying these types of subjects at the time, the shoemaker was extraordinarily sensitive to how these subjects lived their lives, and how family members and communities responded to their embodied differences.

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

Early modern disability history is beginning to take off now, but much of the field remains uncharted. In the first instance, I hope this study contributes to the conversations in that field. There has recently been some debate about how autobiographical sources should be used, but because they are relatively rare, much of this discussion is often somewhat abstract. I would hope to offer some concrete examples of how an autobiographical text like Sebastian Fischer’s notebook could be deployed in productive ways, while also being critical and clear-eyed about its limitations and silences. Beyond that, my goal is ultimately for this work to be useful in an undergraduate classroom, so I’m hoping that it will invite more students into the study of disabled and other marginalized subjects in the premodern past.

Mark Evan Bonds

Project: Music’s Fourth Wall and the Rise of Modern Listening

Mark Evan Bonds is the Cary C. Boshamer Distinguished Professor of Music at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where he has taught since 1992. He holds degrees from Duke University (BA), Universität Kiel (MA), and Harvard University (PhD). A former editor-in-chief of Beethoven Forum, he has written widely on the music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven and is particularly interested in the intersections of philosophy and music since the Enlightenment.

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions that you are considering?

I regularly teach a course in music appreciation and have even authored a reasonably successful undergraduate textbook that teaches students how to listen to music of all kinds, regardless of time or place. But when, I wondered, did listening come to be regarded as a skill? If we’re lucky enough to be able to hear, isn’t that enough? For most people, it is: we resonate with the music we’re hearing and become part of it. But over the course of the nineteenth century, particularly in the concert hall, a different kind of listening emerged, one that was reflexive, listening in effect from the composer’s perspective and trying to grasp what the composer was “saying” in any given work.

In the course of your research have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

Reflexive listening is clearly the gold standard in the concert hall of today: it’s why we have program notes, pre-concert lectures, composer biographies, and how-to-listen books. Paradoxically, however, resonant listening is in its own way a higher goal, for when music possesses us the experience can be transcendental: we are elevated and transported to a different state, we “lose” ourselves in the music. How, then, might we “un-learn” what we have been taught about listening? How can we transcend our own knowledge?

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

Emotions are central to the musical experience, but scholars tend to avoid talking about them. By looking at the conflict between resonant and reflexive listening as a historical phenomenon and by putting it in the broader perspective of aesthetics in general, I hope to lessen this resistance. I also hope that this historical perspective will help us rethink—or even better, replace—the prevailing conceptual dichotomy between “classical” and “popular” music by shifting the focus away from musical styles and toward modes of listening.

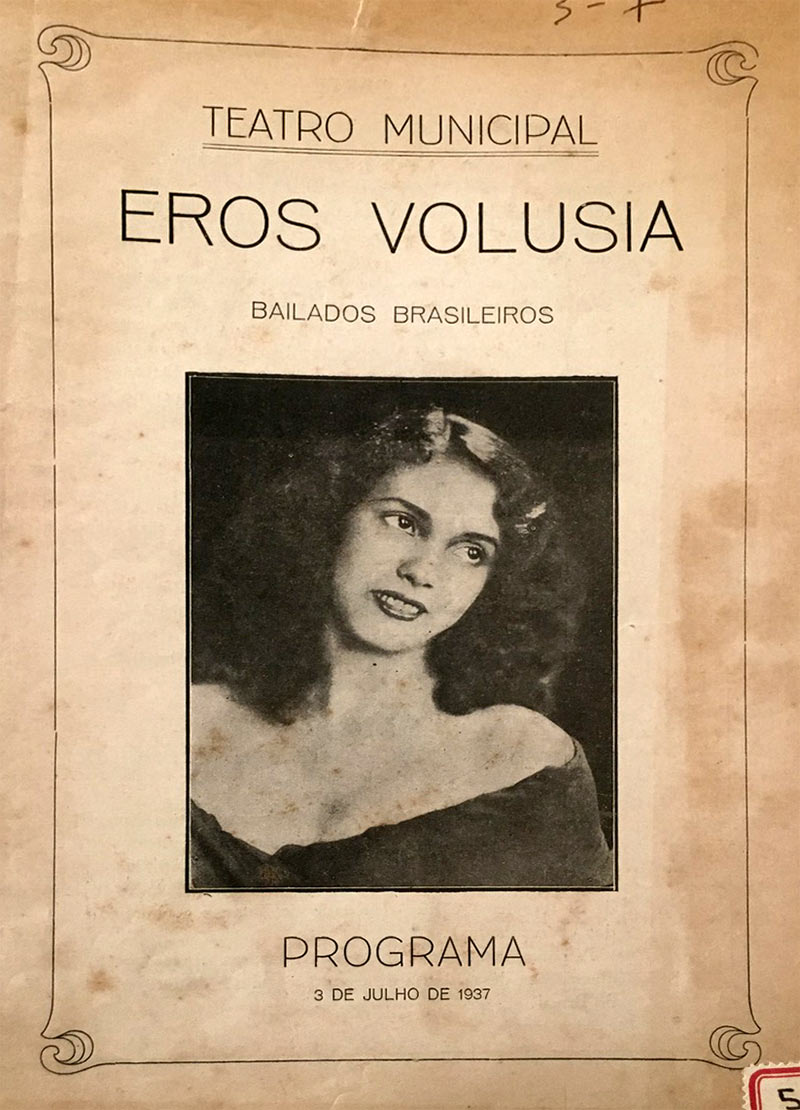

Ana Paula Höfling

Project: Dancing Brazil’s Other: Choreographies of Race, Class, and Nation

Ana Paula Höfling is associate professor and director of graduate studies in the School of Dance at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. She is also an Honors College Faculty Fellow and cross-appointed faculty in the Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality program. She holds a PhD in Culture and Performance from the University of California, Los Angeles and she was an Andrew Mellon postdoctoral fellow at the Center for the Americas at Wesleyan University. Höfling is an RAD-trained ballet dancer and a capoeirista, having studied with Mestre Acordeon, Mestre João Grande, and with Mestre Jogo de Dentro and the Grupo Semente do Jogo de Angola. She is the author of Staging Brazil: Choreographies of Capoeira (Wesleyan University Press, 2019), a history of the process of staging capoeira as both national sport and Brazilian folklore between 1928 and 1974, focusing on issues of race, class, and authorship.

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions that you are considering?

When I came across the work of Brazilian dancer and choreographer Eros Volúsia and realized how famous she had been during her lifetime, I wondered how it was possible that I had never heard of her. I then came across two other choreographers who were contemporaries of Volúsia, Felicitas Barreto and Mercedes Baptista, and saw commonalities (but also crucial differences) between their choreographic projects, which involved using ballet training to explore “folkloric” themes in their choreography. I am looking at representations of the “folk” (a group of people that is always “other” to the group defining these “others” as “folk”) in relationship to emerging notions of Brazil as a racially harmonious nation in the early twentieth century.

In the course of your research have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

I am fascinated by the boldness of these three women, who dared to be in positions of power as directors of their own dance companies in Brazil in the 1940s and ’50s. Not content with reproducing old ballet tropes (but also falling back on these same tropes from time to time), they each conducted ethnographic research and expanded definitions of concert dance in Brazil. Felicitas Barreto, a blonde, German-born Brazilian, shocked Brazil by living for many years among Indigenous communities in Brazil at a time when women traveling anywhere alone, let alone to Indigenous tribes in the Amazon, was a bold undertaking.

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

This research project seeks not only to rectify the erasure of these women from Brazilian dance history but also to ask why a student of dance in Brazil, even today, is more likely to know who Isadora Duncan or Martha Graham were than to know anything about these three Brazilian “pioneers.”