This month we highlight the research of Fellows from the class of 2022–23 whose projects examine the ways that gender and sexuality have been understood across time and in different settings around the world.

Emmanuel David

University of Colorado Boulder

Mariska Leunissen

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Brian Lewis

McGill University

Patricia A. Matthew

Montclair State University

Shailaja Paik

University of Cincinnati

Emmanuel David

Project: Trans-American Orientalism: The Asia-Pacific Encounters of Transgender Pioneer Christine Jorgensen, 1961–1969

Emmanuel David is associate professor of women and gender studies at the University of Colorado Boulder, where he also codirects the certificate program in LGBTQ studies. He is the author of Women of the Storm: Civic Activism after Hurricane Katrina (University of Illinois Press, 2017) and coeditor of the anthology The Women of Katrina: How Gender, Race, and Class Matter in an American Disaster (Vanderbilt University Press, 2012). His recent research on gender and sexuality in the Philippines has focused on a wide range of topics, including global call centers, the politics of beauty pageants, sex work and militarism, and contemporary art and performance. David’s current project explores transgender pioneer Christine Jorgensen’s little-known performance tour across Asia and the Pacific, especially her extended stay in the Philippines.

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions that you are considering?

For the past decade, I’ve studied gender and sexuality in the Philippines. At some point, I came across Susan Stryker’s wonderful article on Christine Jorgensen’s trip to the Philippines. I sought to learn more and read everything I could about Jorgensen’s life. When I realized that there wasn’t much about this chapter of Jorgensen’s life, I set out to see what else I could find. I travelled to Jorgensen’s archive in Copenhagen to sift through her papers and also to the Philippines, where I retraced her steps to better understand her time there. Overall, my project aims to gain insights into how Jorgensen understood Asia and how those in Asia understood her. I’m hoping this work fills a gap in Jorgensen’s otherwise well-documented life and provides new knowledge about how trans people were understood across transnational contexts.

In the course of your research have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

Even though Jorgensen’s trip to the Philippines was over 60 years ago, I was surprised by the ways that history came “alive” for me when I retraced her travels to places like Manila. Being on the ground, I could stand in the places where she stood and imagine her encounters with different types of Filipinos, whether the stars and luminaries of the day or everyday Filipinos. And while most of my research brought me to library and museum archives, I also scoured the antique shops and used bookstores for old newspapers and magazines. On an afternoon outing, I found a stack of dusty newspapers, one of which included an advertisement from Jorgensen’s Philippine engagements. So I was surprised that, with a just little digging, these pieces of history could still be located out in the world.

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

I hope this research prompts additional explorations into the intersectional and global aspects of queer and trans lives. My project has been made possible by numerous scholars—including Aren Aizura, Howard Chiang, Kale Fajardo, and Susan Stryker, among many others—whose work laid out the theoretical and empirical foundation for a project like this, giving me important points of departure. And there is still much to be explored when it comes to the global dimensions of US LGBTQ history, as well as the role of whiteness and American empire in transnational encounters. So I hope that research like this can inspire new thinking about trans lives and other forms social difference as well as connections between the past and the present.

Mariska Leunissen

Project: Facts, Evidence, and Observation: Aristotle’s Natural Scientific Study of Women and Motherhood

Mariska Leunissen is professor of philosophy at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Her main research interests are in Aristotelian natural philosophy and philosophy of science, and more recently in Aristotle’s natural scientific study of women and motherhood and its intersection with representations of conception, pregnancy, and motherhood in ancient medicine and Greek tragedy. She is the author of two monographs on Aristotle, Explanation and Teleology in Aristotle’s Science of Nature (CUP 2010) and From Natural Character to Moral Virtue in Aristotle (OUP 2017). She is also the editor of Aristotle’s Physics: A Critical Guide (CUP 2015) and coeditor of Interpreting Aristotle’s Posterior Analytics in Late Antiquity and Beyond (Brill 2011). She currently serves on the board of directors for the Journal of the History of Philosophy and on the editorial board of Apeiron.

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions that you are considering?

The immediate spark was an invitation to contribute to a handbook about women and/in ancient philosophy: I loved the project and wanted to contribute, but didn’t want to write again about how Aristotle thinks women are inferior to men. There was also a lingering frustration: Aristotle is such a brilliant empirical scientist, and yet he made stupid mistakes about women. My project is about trying to understand how Aristotle studied women, and specifically, whether he thought women and their bodies were not just objects of study, but also sources of knowledge about their own bodies and experiences. So I’m interested in finding out what Aristotle thought about topics like female pleasure during sex, women’s knowledge of conception, and the experience of childbirth, and especially in his methods and sources for gathering this information.

In the course of your research have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

I knew Aristotle’s views were influenced by the ancient medical tradition, but I was surprised by how often he paraphrases (plagiarizes?) from their texts in discussing “female facts” without mentioning his source or indicating his engagement with medical views. I was also surprised by Aristotle’s reliance on Greek tragedy as a source of information for women’s inner feelings. I was also positively surprised by some of the things that Aristotle did seem to know about women (e.g. he seemed to have known about back labor and its association with more difficult births, he refers to the clitoris—a part not discussed by the ancient medical writers or anyone else that I know of in his time, the increased risk of maternal mortality in young girls, and his recommendation that girls should not marry and start having children until they are 18).

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

I hope that this project will provide a way to engage with Aristotle and his views on women in a way that isn’t entirely negative and that opens up his texts as a not yet fully explored resource for the reconstruction of the voices of the women of classical Athens themselves, so that we learn more about them. In previous work, I argued for the need to read Aristotle systematically in the context of his entire corpus, but this project is showing how much Aristotle is also drawing from and is influenced by other contemporary philosophers, physicians, and poets and that we can benefit from reading Aristotle contextually. I’m neither the first nor the only one arguing for this, but I hope that this project adds strength to the chorus.

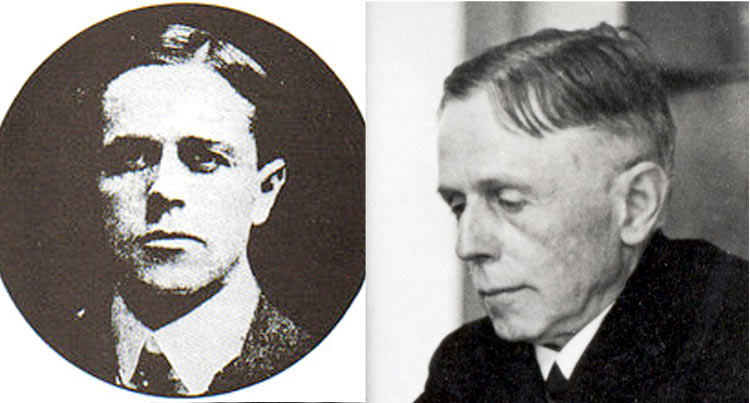

Brian Lewis

Project: Greek to the Soul: George Ives and Homosexuality from Wilde to Wolfenden

Brian Lewis is professor of history at McGill University and a historian of modern Britain. His first substantial book, The Middlemost and the Milltowns, analyzes the leading members of the middle classes of Lancashire cotton towns between 1789 and 1851, assessing their economic, cultural, and political contributions to the creation of social stability. His second book, So Clean, is a study of William Hesketh Lever, 1st Viscount Leverhulme (1851–1925), the founder of the Lever Brothers’ Sunlight soap empire. His third monograph, Wolfenden’s Witnesses, is an annotated selection of the papers of the Wolfenden Committee, which was set up in 1954 to investigate the state of the law regarding homosexuality and prostitution. Lewis’s current project, Greek to the Soul: George Ives and Homosexuality in Britain from Wilde to Wolfenden, is an investigation of (homo)sexuality and criminality in Britain between the 1880s and the 1950s using Ives, pioneer “gay rights” campaigner and penal reformer, as its focus.

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions that you are considering?

I first came across George Ives in the writings of British queer historians Jeffrey Weeks and Matt Cook. What intrigued me most about him was not so much his (substantial) contribution to queer rights activism as his writing of a massive diary between 1886 and 1949, which had found a home at the Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin. Scholars had dipped into this, but no one—so far as I could tell—had read through all of it. It seemed to me that the Ives archive had the potential—and this turned out to be accurate—to bring the granular detail of individual lived experience to one of the staples of queer history: How and why, in the few decades either side of 1900, did the Western world rethink basic understandings of human sexuality?

In the course of your research have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

Ives’s complicated understanding and fashioning of his sexuality and gender identity surprised me the most. It seems to me to amply support the contentions of those queer historians, influenced above all by Eve Sedgwick, who have emphasized not so much Michel Foucault’s famous sexual invert as a new “species” (with a distinct identity, psychology, and pathology), created by sexologists in the late nineteenth century, but rather overlapping and colliding discursive formations and social types—multiple ways for men-loving men and women-loving women to understand themselves and be understood.

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

With my emphasis on nuance and complexity, I hope that my study will make a strong contribution towards the “sexual turn” in social, cultural, and urban history. Ives, a footsoldier in and a chronicler of a sexual revolution, always believed that his biography would be written one day and that his diary—with all its vivid details of sexual and gender nonconformity and queer domesticity and sociability—would be discovered as “a mine for the making of history.” His time has come.

Patricia A. Matthew

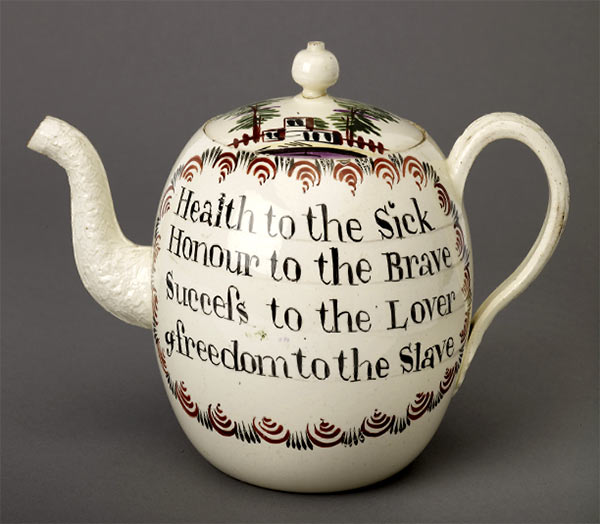

Project: Gender, Sugar, and the Afterlives of Abolition

Patricia A. Matthew is associate professor of English at Montclair State University and a specialist in the history of the novel, Romantic-era fiction, and British abolitionist culture. She has edited special issues of the journals Romantic Pedagogy Commons, European Romantic Review, and Studies in Romanticism and published articles and reviews in Women’s Writing, the Keats-Shelley Journal, and Texas Studies in Literature and Language. Her essays on race and the Regency have been published in The Atlantic, Lapham’s Quarterly, and the Times Literary Supplement. She is coeditor of Oxford University Press’s series Race in Nineteenth-Century Literature and Culture and will edit Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park for W.W. Norton. Her first book, Written/Unwritten: Diversity and the Hidden Truths of Tenure (University of North Carolina Press, 2016), was an edited volume about the experiences of faculty of color in higher education. Her current book project is a study of gender politics in Britain’s abolitionist culture and contemporary Black art.

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions that you are considering?

While preparing a lecture for a British abolitionist literature course, I found a website that illustrated its overview of the 1790s anti-sugar boycott with a ceramic teapot. It was decorated with palm trees and a short poem that ends: “Success to the Lover/And Freedom to the Slave.” Domestic objects like this teapot were designed for white women to broadcast their anti-slavery sentiments. My book project recontextualizes them to answer a set of interlocking questions: How is political economy feminized between 1790 and 1830 with the anti-sugar boycott? How do generic differences, between poetry and fiction and paintings and ceramics reflect representations of Black and mixed-race figures? What is the connection between notions of amelioration and the emergence of Blackness as a philanthropic in the abolitionist project?

In the course of your research have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

This summer in England I met with curators and private collectors to learn more about the objects I focus on in the book. At the Victoria and Albert Museum and at the home of a private collector, I had the opportunity to hold objects I have been looking at online and in museum displays for the last six years. I was awestruck by the experience. I held teapots, sugar bowls, tea canisters, bowls, and egg cups. Some of them felt much heavier than they looked while others were more delicate. My book is critical about why and where these objects circulate; handling them so intimately, seeing the depictions of Black figures on them up close deepened my understanding of their impact on Regency domestic culture.

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

My book reads Regency-era abolitionist culture through the work of contemporary Black artists. In doing so, it will teach multiple sets of readers how to recognize unexamined connections between nineteenth and twenty-first century racial politics. Specialists who focus on the history of the novel, Romantic poetry, and regency-era literature and reading audiences who still love Jane Austen and her world usually imagine her nineteenth-century England worlds away from its reliance on the slave trade. It also offers a methodology that shows how to center the experience of Black women, even when they seem to be missing from the archives.

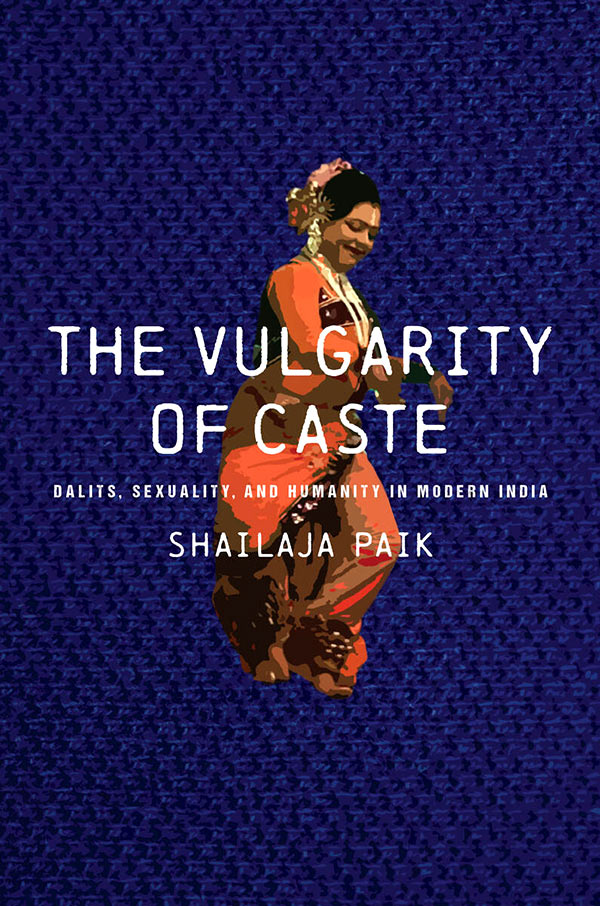

Shailaja Paik

Project: Becoming “Vulgar”: Caste Domination and Normative Sexuality in Modern India

Shailaja Paik is Taft Distinguished Professor of history and an affiliate in women, gender, and sexuality studies at the University of Cincinnati. Her first book, Dalit Women’s Education in Modern India: Double Discrimination (Routledge, 2014), examines the nexus between caste, class, gender, and state pedagogical practices among Dalit (“Untouchable”) women in urban India. Her second book, The Vulgarity of Caste: Dalits, Sexuality, and Humanity (Stanford University Press, forthcoming), focuses on the politics of caste, class, gender, sexuality, and popular culture in modern Maharashtra. She is currently working on her third monograph, Becoming ‘Vulgar’: Caste Domination and Normative Sexuality in Modern India, and coediting a book on Dr. B.R. Ambedkar (Cambridge University Press, forthcoming).

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions that you are considering?

I grew up watching Tamasha along with other popular art forms during the summers I spent in my village. While playing with friends and family, we children also sang songs and enacted the song and dance. There is no systematic historical analysis of the violence, stigmatization, and oppression of these artists. It was only after I embarked on my field research with Tamasha women, starting in 2003, that I turned my attention to the systemic sexual-caste violence that, despite some breaches, served to keep the structure of agrarian-caste slavery intact. I ask, How and why did vulgarity and disgust become a primary framework to understand caste sociality and sexuality? How did Dalits come to be designated as vulgar, and how did some Dalits come to be designated more vulgar than others due to the politics of caste, gender, and sexuality?

In the course of your research have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

I have conducted field research over the last 25 years. For the current project, I was interviewing artists engaged in the public performance of Tamasha in Western India. Most artists are poor, oppressed, and at the same time work the system to make financial, social, and political gains. During my fieldwork in a village in 2016 I was surprised to learn that a lead-woman artist, Mangalatai Bansode owned an RV and 25 trucks and oversaw a troupe of 200–250 people. She was a thorough entrepreneur ordering people around, including family members. She offered me a ride to Pune, and I rode in an air-conditioned RV for the first time. I usually use local transportation—buses, trains, auto-rickshaws.

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

My work opens up new approaches for the transformative potential of Dalit politics and the global history of gender, sexuality, and the human. I illuminate how Dalit women bent patriarchal pressures both inside and outside the Dalit community and became foundational actors in conflicts over caste, class, culture, gender, and sexuality. Building on and departing from the Ambedkar-centered historiography and movement-focused approach of Dalit studies, I examine the ordinary and everydayness in Dalit lives, both illustrating how sexuality, vulgarity, and violence framed the political recognition and political constituency of the new Dalit community.