This month we highlight the research of Fellows from the class of 2022–23 whose seemingly disparate projects both examine the vital role that texts and creative works play in establishing authority and shaping systems of belief.

David Brakke

The Ohio State University

Kiu-wai Chu

Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

David Brakke

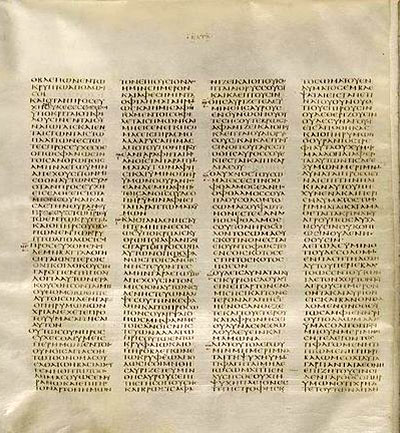

Project: A Religion of the Books: The New Testament and Other Early Christian Scriptural Practices

David Brakke is Joe R. Engle Chair in the History of Christianity and professor of history at The Ohio State University. He is the author, coeditor, or cotranslator of more than a dozen books on monasticism, Gnosticism, biblical interpretation, and Egyptian Christianity in late antiquity, most recently The Gospel of Judas: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary (Anchor Yale Bible, Yale University Press 2022) and, with David Gwynn, The Festal Letters of Athanasius of Alexandria, with the Festal Index and the Historia Acephala (Translated Texts for Historians, Liverpool University Press 2022). He has served as editor of the Journal of Early Christian Studies and president of the International Association for Coptic Studies.

Brakke’s current project, A Religion of the Books: The New Testament and Other Early Christian Scriptural Practices, contextualizes the formation of the New Testament within the diverse ways early Christians created and used authoritative writings. He is also working on a new translation and study of the Secret Book (Apocryphon) of James.

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions that you are considering?

Some years ago I was examining the Easter letter that Bishop Athanasius of Alexandria wrote in 367 CE. It’s famous because it’s the earliest known Christian document to list precisely the 27 books that make up the New Testament canon. I knew that only a few paragraphs of the original Greek survived, but I did not know that most of the letter survives in a Coptic translation, that the Coptic text provides evidence for why Bishop Athanasius established a closed canon, and that very few scholars had studied the text. It led me to ask, Was a closed canon the only option available to bishops in the fourth century? Were there Christians who used scriptures differently? What circumstances motivated bishops like Athanasius to establish the canon?

In the course of your research have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

The listing of a closed canon of the New Testament in the fourth century appears to have had effects on Christian literary culture that I did not anticipate. It inspired Christian intellectuals to create other lists, for example of important Christian writers and of their books. They began to produce new works about New Testament characters or purportedly written by them that were self-consciously non-canonical or apocryphal. Christians used New Testament texts orally and/or written on pieces of paper or clay in ways that would alarm bishops like Athanasius (“magic”). Closing the New Testament didn’t close Christian scriptural creativity.

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

I hope that my research will inspire other scholars to explore specific early Christian scriptural practices in ways that do not ignore the formation of the New Testament, but also that don’t see it as inevitable or as only limiting of Christian literary activity.

Kiu-wai Chu

Project: Chinese Eco-Images in The Planetary Age: The Multispecies World of Humans, Animals, and Plants

Kiu-wai Chu is assistant professor in environmental humanities and Chinese studies at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. He is an Executive Councillor of the Association for the Study of Literature and Environment (ASLE-US), and Living Lexicon editor of the open-access journal Environmental Humanities (Duke University Press). His research focuses on environmental humanities, ecocriticism, and contemporary cinema and visual art in Asia. His work has appeared in Transnational Ecocinema; Oxford Bibliographies; Journal of Chinese Cinemas; Asian Cinema; Chinese Environmental Humanities; photographies; Screen; and elsewhere.

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions that you are considering?

I believe it was the ubiquitous urban ruins, abandoned demolition and construction sites, and garbage dumps in cities of China I saw in film, photography, and art works at the turn of the century, that started my concern about how the country’s processes of urbanization and commercialization are drastically transforming and shaping the environment, as well as those inhabiting it. And in attempt to understand the country’s growing emphasis on building a “green modernity” and an “ecological civilization,” my project aims to put in perspective the tensions and conflicts between the aesthetic-philosophical ideals in the official environmental narrative; and the everyday socio-political realities, to examine the role film, art, and visual media play in addressing and revealing these ecological contradictions and ambiguities.

In the course of your research have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

Generally, what has surprised and amused me in the course of conducting my research is the finding of oddest linkages and connections among seemingly unrelated things, people, and concepts, and how they all turn out to be closely related, connected, and intermingled. There appears to have little in common among what Daoist sage Zhuangzi or Confucian political thinker Kang Youwei have said about nature and the animal world; with the theoretical propositions by scholars in environmental humanities; or creative works by contemporary filmmakers and artists. But despite the contrasting cultural practices and ideological beliefs in their respective times of existence, one would be surprised to find that their envisioning of the forms of ecological utopia and challenges encountered in the process, could fundamentally be very similar.

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

My approach to address the above-mentioned questions is through examining the roles cinema, visual art, and culture (the “eco-images”) play in shaping our perceptions and relationships with the more-than-human world (animals, plants, and the environment) in a world of interconnectedness. The project aims to expand the scope of environmental humanities beyond western theoretical approaches, by highlighting the relevance and currency of classical and modern Chinese aesthetic and philosophical concepts, particularly those of Shan Shui, Feng Shui, and Da Tong (a Confucian utopian vision of Great Unity) in environmental aesthetics, ethics, philosophy, and Anthropocene studies; and in turn, to promote comparative and relational approaches in environmental humanities that take us beyond conventional understanding of progress and sustainability.