This month we highlight the research of Fellows from the class of 2023–24 whose projects consider the ways that lived experience is colored, configured, and interpreted. Through a variety of approaches, each of these scholars is exploring the ways that thought, feeling, and custom produce subjective lenses through which we encounter the world and extract meaning.

Sequoia Maner

Spelman College

Richard J. Powell

Duke University

Jonathan Sachs

Concordia University

Elanor Taylor

Johns Hopkins University

Sequoia Maner

Project: A Critical History of Black Elegy in the United States

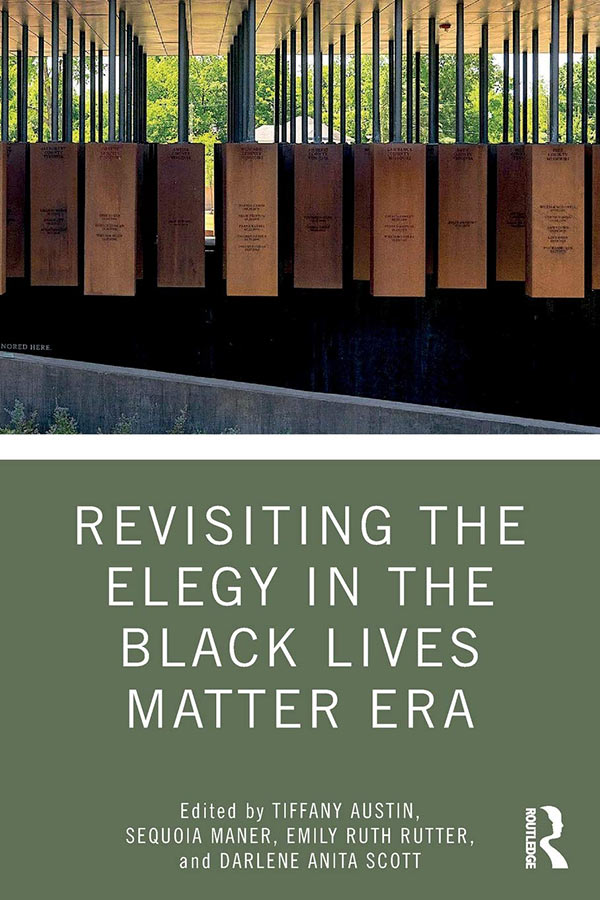

Sequoia Maner is assistant professor of English at Spelman College where she teaches classes related to African American literature and culture. She serves as secretary on the Board of Directors of TORCH Literary Arts, a nonprofit organization for Black women writers, and is a mentor with PEN America’s Incarcerated Writers Bureau (IWB). She is a poetry fellow of The Watering Hole and the Hurston/Wright Foundation. Maner is author of Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly (33 1/3 series, Bloomsbury Academic Press, 2022) and the prize-winning chapbook Little Girl Blue: Poems (Host Publications, 2021). She is coauthor of the book Revisiting the Elegy in the Black Lives Matter Era (Routledge, 2020). Her poems, essays, and reviews can be found in venues such as Meridians, Obsidian, The Langston Hughes Review, The Feminist Wire, Auburn Avenue, and elsewhere.

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions that you are considering?

Rather than a spark, this book has unfurled like a slow-smoldering fire. As a reader and writer of poetry living during a time shaped by death and loss, I found myself engaged by the project of the elegy, by the work of mourning and memorializing. I’ve been thinking through the many textures of the elegiac mode for some time now, and in doing so, have turned to masters of the African American poetic tradition as lodestars: Wheatley-Peters, Hughes, Brooks, Cortez, Clifton, and so many others. Black poets know a thing or two about writing in the wake of death, especially those deaths that are public, tragic, unnatural, and thought to be unspeakable.

In the course of your research have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

I am inspired by the boundless ways poets have transmitted simple messages like: “I loved you, even if I didn’t know you;” “I will continue to think of you;” “You didn’t deserve a death like this;” “You are gone too soon;” “I was not ready to mourn your loss;” “I speak your name.” And while it is not surprising that Black poets illuminate absolutely elemental aspects of human emotion, I remain astounded by the range of innovation regarding expressions of grief in the wake of death.

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

I think my approach to elegy opens up interesting conversations about historicization and timeliness. For example, consider how in elegizing Frederick Douglass, poets such as Cordelia Ray, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Robert Hayden, and Evie Shockley, among many others, emerge as a cadre of living and historical poets who animate, pay homage to, complicate, and contextualize the great abolitionist. This model of achronological clustering that moves fluidly across centuries allows for expansive thinking and reframing of literary genealogies which are too often, temporally bounded.

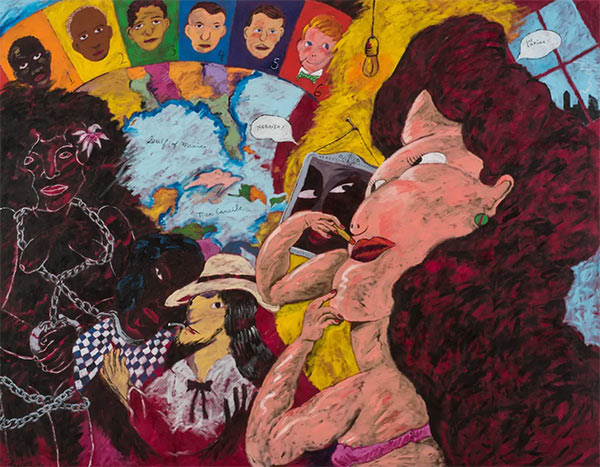

Richard J. Powell

Project: Colorstruck! Painting, Pigment, Affect

Richard J. Powell is the John Spencer Bassett Distinguished Professor of Art and Art History at Duke University, where he has taught since 1989. Along with teaching courses in American art, the arts of the African Diaspora, and contemporary visual studies, he has written on a range of topics, including such titles as Homecoming: The Art and Life of William H. Johnson (1991), Cutting a Figure: Fashioning Black Portraiture (2008), Going There: Black Visual Satire (2020), and Black Art: A Cultural History (1997, 2002, and 2021). An authority on African American art and culture, he has also organized numerous art exhibitions, most notably The Blues Aesthetic: Black Culture and Modernism (1989); Rhapsodies in Black: Art of the Harlem Renaissance (1997); To Conserve A Legacy: American Art at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (1999); Back to Black: Art, Cinema, and the Racial Imaginary (2005); and Archibald Motley: Jazz Age Modernist (2014).

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions that you are considering?

Seeing the 2015 Museum of Modern Art exhibition One-Way Ticket: Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series and Other Visions of the Great Movement North prompted me to reconsider Lawrence’s work in the context of color, and this led to considering the chromatic dynamics operative in other artists’ paintings.

In the course of your research have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

I was surprised by the problematic position the color brown has in color theory, and the attendant debates surrounding its study. Although brown is not present in the conventional color wheel, many color theorist nevertheless consider it an elemental color, along with red, blue, green, etc.

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

Further art historical research on the interconnections between a work of art’s formal aspects and its cultural context.

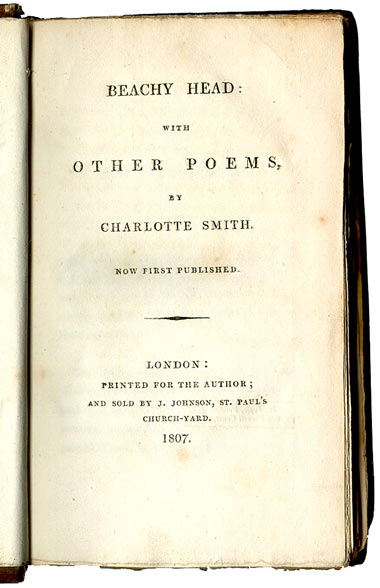

Jonathan Sachs

Project: Slow Time

Jonathan Sachs is professor of English at Concordia University in Montréal. His work focuses on British literature from 1750 to 1850, exploring the role of literature in constructing historical and temporal experience, including the uses of antiquity, the anticipation of the future, and practices of reading. Sachs is the author of The Poetics of Decline in British Romanticism (Cambridge University Press, 2018), Romantic Antiquity: Rome in the British Imagination, 1789–1832 (Oxford University Press, 2010), and the coauthor, with The Multigraph Collective, of Interacting with Print: Elements of Reading in an Era of Print Saturation (University of Chicago Press, 2018). He has recently finished, with Andrew Stauffer, a new one-volume edition, Lord Byron: Selected Writings for the Oxford University Press series 21st-Century Oxford Authors. Sachs has served as the Principal Investigator of the Interacting with Print Research Group (2014–2020), as the Romanticism Section editor of Blackwell’s Literature Compass (2015–2020) and as a member of the MLA’s Executive Committee for Later Eighteenth-Century Literature (2015–2020).

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions that you are considering?

From the “Slow Movement” to Jenny Odell, so much recent thinking encourages us to slow down and step back from the speed of digital media and contemporary life. Reading this work I was struck by how much this polemical emphasis on slowness resonated with the Romantic poetry that I study. How do we understand the value placed on slow time in this work: is it merely reactive to the acceleration of contemporary life or does it reveal an undercurrent of potentially slower experiences that are also fundamental to the modern sense of time? And how might thinking about the proliferation of print at an earlier historical moment help us to think more broadly about how societies adjust to the speed of new media?

In the course of your research, have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

Every new project produces surprises! One that jumps out about this project is how badly I had previously gotten Wordsworth’s poetry wrong. I had read Wordsworth as an apostate conservative whose poetry was often banal. But, guided by the work of Geoffrey Hartman, David Simpson and others, I have now come to see that so little happens in so much of Wordsworth’s poetry by design. He is trying to teach us how to pay attention differently. Thinking about Wordsworth as a poet of bewilderment in the face of novelty and change—and his poetry as a vehicle for articulating what it means not to know or understand something—opened up for me the importance of his work.

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

My project argues that one of Romanticism’s overlooked but defining features is a sense of uneven time that responds to a sense of slowness overlapping with the acceleration of contemporary life. In this way, I hope that this book contributes to the renewed attention to time and what some are calling the “temporal turn” in Romantic studies. More broadly, I want to suggest that attending to the representation of acceleration and slowness in Romantic poetry has much to teach us as we try to understand the hurry of our modern life and as we think about the risks and opportunities for contemporary life brought by emergent technologies, big data, and new media.

Elanor Taylor

Project: The Foundations of Social Metaphysics

Elanor Taylor is associate professor of philosophy at Johns Hopkins University (JHU). She received her PhD in philosophy from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 2012, and was an assistant professor of philosophy at Iowa State University before moving to JHU in 2017. Taylor works mostly in metaphysics, particularly metaphysics of science and social metaphysics, and is especially interested in questions about connections between explanation and metaphysics. While in residence at the National Humanities Center, Taylor will be working on a book project titled The Foundations of Social Metaphysics. This project concerns the nature and possibility of social metaphysics, and connects these issues to broader philosophical questions about what it is to be a realist, and about connections between realism and inquiry.

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions that you are considering?

Metaphysics is the study of the nature and structure of reality. Social metaphysics applies the tools of metaphysics to social entities such as classes, institutions, genders, and ethnicities. Recently some have argued that traditional metaphysical frameworks are not appropriate for social metaphysics, given that they were not developed for social subject-matter. While reflecting on these issues I realized that the apparent challenges for social metaphysics instantiate a common pattern that appears across many different areas of philosophy, in attempts to connect realism, mind-independence, and the legitimacy of inquiry. Accordingly this project engages with big-picture questions about what it is for something to be real, what it is to be a realist, and how realism is connected to the legitimacy or otherwise of inquiry.

In the course of your research have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

I have found myself surprised by the amount of research in the humanities relevant to core issues in general analytic metaphysics, such as questions about existence, reality, and different ways in which things can depend on other things, that is not typically taken up in that literature. This includes research from history of science on the nature of objectivity, from anthropology on the development of the notion of reality, and from feminist theory on social structure. Most analytic metaphysicians acknowledge that their work must be responsive to and informed by the natural sciences—I recommend extending this commitment to include the humanities, the arts, and the social sciences.

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

I have three main goals for this project. The first is to articulate and defend a metaphysical framework that accommodates social metaphysics and resolves some long-standing issues for other areas of metaphysics. In doing so I hope to offer solid foundations for social metaphysics and to vindicate its standing as metaphysics. The second is to offer diagnostic tools that illustrate connections between a range of different problems across different areas of philosophy. The third is to model a more expansive conception of the bodies of work to which analytic metaphysics should be responsive and relevant, moving away from merely basic research in the natural sciences and towards encompassing research in the arts, humanities, and social sciences.