In this issue we highlight the research of Fellows from the class of 2021–22 who are exploring the ways that religious thinking and practice have been interwoven in the fabric of our societies.

Barbara Kowalzig

New York University

Timothy L. Stinson

North Carolina State University

Barbara Kowalzig

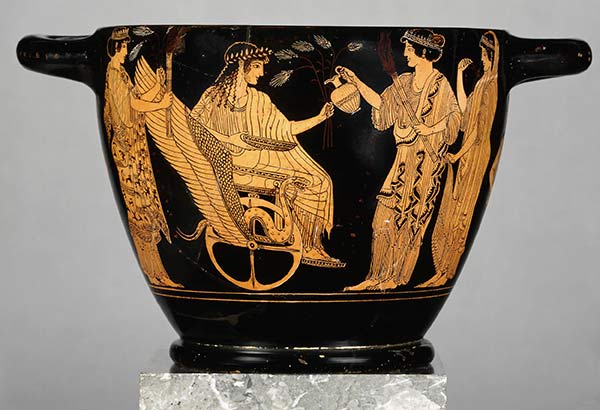

Project: Gods around the Pond: Religion, Society and the Sea in the Early Mediterranean Economy

Barbara Kowalzig is associate professor of classics and history at New York University. A historian of ancient Greek religion in its broader Mediterranean context, she has a particular interest in the role of religion in the social and economic transformation of the ancient world. Her work engages with long-term Mediterranean history and anthropology, and comparative and cross-disciplinary approaches to the study of premodern societies. She has published widely on the social efficacy of ritual, music, and performance and is the author of Singing for the Gods: Performances of Myth and Ritual in Archaic and Classical Greece (Oxford University Press, 2007). Her project at the NHC is entitled Gods around the Pond: Religion, Society and the Sea in the Early Mediterranean Economy. Drawing from a range of social sciences, it explores the interaction of religious practices and economic patterns in the Mediterranean from the Late Bronze Age to the early Hellenistic period (ca. 1250–ca. 200 BCE). It seeks to understand ancient Greek religion as emerging from the broad, transcultural context of maritime economic mobility. In particular, the book traces how religious and economic transformation went hand in hand, suggesting that ancient polytheism was inextricably intertwined with economic growth and decline. Within this framework, the book explores topics such as the generation of a maritime belief system; the role of religion and cross-cultural trade; the association of divinity with commodities in civic economies; cultic pluralism and economic growth in cosmopolitan port-cities.

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions that you are considering?

During my previous work on song-culture, ritual performance, and social change, I noticed that myth, ritual, and cult tended to map out not just social and political identities in interconnected landscapes, but also geographies of economic collaboration and complementarity across maritime spaces, island worlds, and coastal communities. That got me thinking more broadly about the role of the connectivity of ancient polytheism—that is to say the social networks that interlinked myths, rituals, and cults produce—in shaping and being shaped by the economic connectivity of the ancient Mediterranean at large. I soon realized that Greek polytheism formed part of a broader, ‘transcultural’ polytheism linking up the sea and offsetting its geographical and ecological fragmentation; it was hence a factor in economic integration.

In the course of your research have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

I wouldn’t necessarily call these ‘surprises’, but at the beginning of this project, I read a lot of current economic theory; and while on the whole we don’t have the evidence to do such modelling, I continue to be struck by how concepts and principles highly theorized today—such as risk, rationality, regulation—in the ancient world are processed in terms of myth, ritual, and cult, and are always understood within an ethical, community-oriented framework. Relatedly, I am intrigued by how self-regulatory a religious system based on oral tradition and collective cult practice can be, or purports to be. So for example, in the Hellenistic period, when public cult is in a sort of funding crisis and elites start to have an outsized role in religious life, that’s just when new gods emerge emphasizing their support for all, regardless of political or social status, the poor, the sick, women, slaves. Polytheism is a bit of a wayward system and cannot easily be controlled by anyone except by collective dynamics; in individual localities, it can be a barometer of communal well-being.

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

Approaches and methods for studying the intertwining of ancient religions with society and politics are well established, but no-one to my knowledge has attempted to look at religious transformation in early Mediterranean history through an economic lens, or vice versa; nor are there many modern paradigms. While no single person can deal with this subject comprehensively, I hope to open up the debate and introduce approaches and models that will inspire future researchers to take this prolific field further. Moreover, religious and economic historians tend to work in opposing intellectual traditions, of social anthropology on the one hand, economic and political theory on the other. I hope that my work can contribute to breaking down some of the boundaries between qualitative and quantitative approaches in history and the social sciences.

Timothy L. Stinson

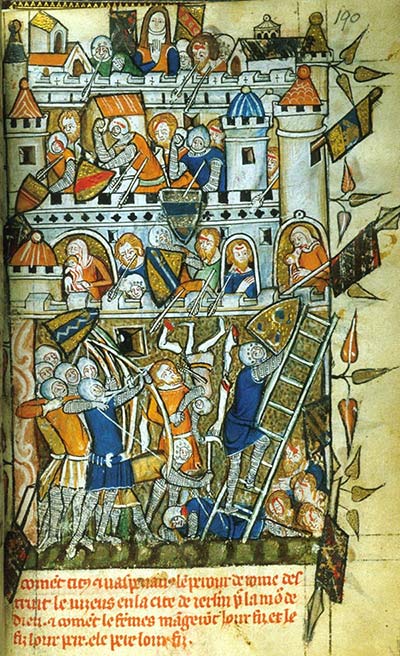

Project: Avenging Christ: Vengeance, Devotion, and Violence in Late Medieval England

Timothy L. Stinson is associate professor of English and a University Faculty Scholar at North Carolina State University. He received his PhD in English language and literature in 2006 from the University of Virginia and was a postdoctoral fellow at Johns Hopkins University for two years prior to joining the North Carolina State University faculty in 2008. He has published in leading journals in the field of medieval studies and book history, including Speculum: A Journal of Medieval Studies, The Yearbook of Langland Studies, Manuscript Studies, and The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America. His research interests include Middle English poetry, codicology, history of the book, and digital humanities. Stinson is a leader in the application of digital technologies to medieval studies. He is cofounder and codirector of the Medieval Electronic Scholarly Alliance, director of the Society for Early English and Norse Electronic Texts (SEENET), codirector of the Piers Plowman Electronic Archive, associate director of the Advanced Research Consortium (ARC), and editor of the Siege of Jerusalem Electronic Archive. Stinson has also collaborated with colleagues in the biological sciences to analyze the DNA found in medieval parchment manuscripts. This work has garnered international press coverage in outlets such as the BBC’s The World Today, National Geographic, Science, and The Chronicle of Higher Education.

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions that you are considering?

My book addresses medieval accounts of the Roman destruction of Jerusalem in 70 AD, which ahistorically claim that the Romans sought to avenge the Crucifixion. I first encountered this story when editing a fourteenth-century poem, The Siege of Jerusalem. At the time I was focused on editorial problems, but the strangeness and apparent popularity of the story stuck with me. So I set out to answer several questions: What about the story made it perennially interesting during a span of almost two millennia? What made it almost endlessly malleable, able to be adapted and revised continually? And what cultural work was the story doing in late medieval England, when few people in England had likely met a living Jew after the Edict of Expulsion in 1290?

In the course of your research have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

By far the most surprising thing has been the scope of this narrative across both time and space. One finds it everywhere—in medieval literature, in bestiaries, in wildly popular plays that took up to four days to perform, in visual arts, sermons, and even on coins. And its popularity never seems to wane from late antiquity through the early modern period. There is broad recognition today that the historical event was important, but relatively few people seem to realize just how important this story was to a wide range of people before, throughout, and beyond the medieval era.

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

I hope to show how medieval concepts of Jerusalem broadly, and of its destruction more specifically, informed what it meant to be Christian and English, and that indeed ideas about Jerusalem versus Rome were bound up with national identity from the outset as the nation of England took shape. In looking at this phenomenon, we not only understand medieval England better, but also the ways that narratives about people and places long ago provide much of the DNA of stories about ourselves and others in the present moment. Unfortunately there is often a downside and darkness to such stories, as violence and ostracization tend to accompany them. But we must confront and understand such things, even when they are deeply uncomfortable.