This month we highlight the research of 2023–24 Fellows whose projects explore the human experience through the lens of settled spaces. By examining the interconnected lives of villagers and city-dwellers in Asia and the Americas and analyzing built spaces that define cultures and identities, these scholars are revealing new insights about the importance of place in understanding the human experience.

Xiaolin Duan

North Carolina State University

Frederico Freitas

North Carolina State University

Tom Johnson

University of York

Stella Nair

University of California, Los Angeles

Xiaolin Duan

Project: Three Cities of the Early Modern Pacific: Connections and Conflicts between the Ming Dynasty and the Spanish Empire

Xiaolin Duan is associate professor of history at North Carolina State University. Duan studies medieval to early modern China, particularly environmental history and visual/material culture. She has published two books: The Rise of West Lake: A Cultural Landmark in the Song Dynasty (University of Washington Press, 2020) and An Object of Seduction: Chinese Silk in the Early Modern Trans-Pacific Trade (Lexington Books, 2022). She is currently working on a project considering the impact of trans-Pacific trade on urban infrastructure. She is also interested in place-product co-branding in Middle period China.

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions that you are considering?

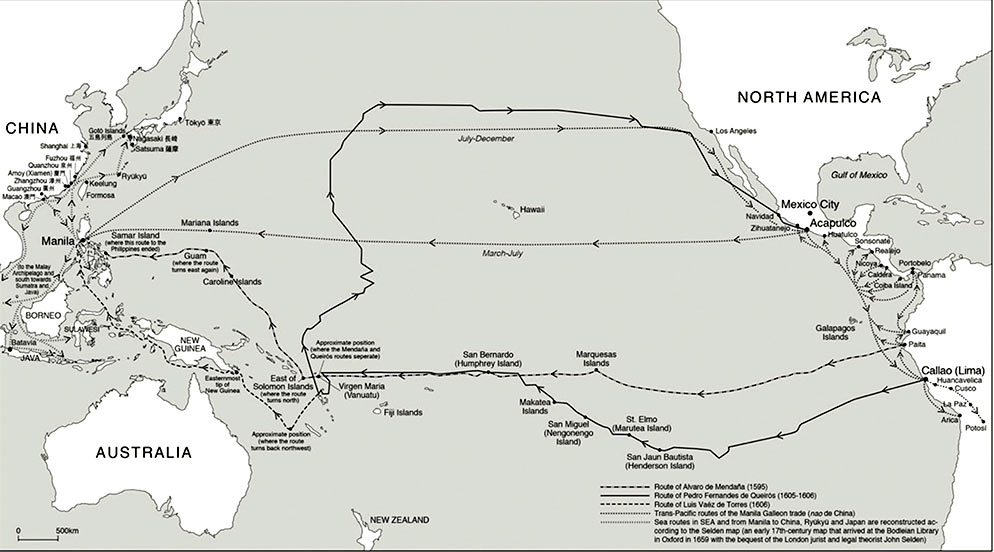

The history of the early modern global network has come to the fore in recent years, yet the impact of the trans-Pacific connection between Asia and America remains largely uncharted. During the 16th and 17th centuries, the Pacific silk trade forged a link between Ming China and colonial Mexico. I propose to investigate the influence of this trade on urban spaces and city life in key ports: Zhangzhou, Manila, and Acapulco. My argument posits that this unprecedented form of globalization generated intimate connections at the everyday life level while simultaneously giving rise to conflicts at the state and empire levels.

In the course of your research, have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

It’s fascinating to observe how different port cities responded to the burgeoning foreign trade in seemingly conflicting yet intriguing ways. Haicheng County in Zhangzhou and Acapulco in New Spain both grappled with the inherent instability of overseas trade by constructing numerous defense structures. Paradoxically, these very port cities also witnessed the emergence of innovative commercial markets tailored to foreign goods. What adds to this narrative is the intricate pattern of migration, particularly the experiences of Fujian locals who sojourned in Southeast Asia while maintaining a strong connection to their hometowns through requests to reconstruct their ancestral shrines. Furthermore, the dominance of Chinese barbers in the Mexican business is another captivating aspect that underscores the early modern migration.

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

I aim to enrich the scholarly discourse on early modern trade from a Pacific perspective. This research introduces the concept of “connected history” into the examination of urban development, shedding light on early modern globalization as a multifaceted phenomenon that encompasses diverse interpretations, intersecting with various urban experiences. My primary focus is the exploration of Ming dynasty foreign policy through an in-depth analysis of the local history of Zhangzhou and its interactions with the wider world. I anticipate that this study will make a valuable contribution to the fields of global history, urban history, and the history of everyday life.

Frederico Freitas

Project: Concrete Tropics: An Environmental History of Brazil’s Modernist Capital

Frederico Freitas is associate professor of Latin American and digital history at North Carolina State University, where he is a core member of the Visual Narrative Initiative. While at the National Humanities Center, he is working on his book-in-progress, Concrete Tropics: An Environmental History of Brazil’s Modernist Capital.

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions that you are considering?

As a planned city built according to modernist principles, Brasília is often cited as the ultimate example of the artificiality of mid-twentieth-century planned urban life. The city’s monumental architecture, car-centric grid system, and functional master plan have set the boundaries for most of the scholarship produced about Brazil’s new capital. A modernist city designed upon utopian ideals, Brasília was to provide a novel urban environment to foster the birth of a modern society. And yet, the city had to contend with the reality of the nature supporting its existence. My project shows how Brasília and the society it created are the products of not only the successes and failures of modernist planning but also the environmental processes that shaped the city’s construction and founding.

In the course of your research have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

One of the most surprising things about Brasília is how little it has been studied by historians of Brazil, particularly in the Anglophone academy. Architectural and urbanism scholars have thoroughly examined the city for its role as a site of experimentation of modernist architecture. Social scientists have also studied Brasília as the prime example of the problems of modernist utopian thinking in the mid-twentieth century. Yet, historians of Brazil have paid little attention to the city. In this way, the city has been used to illustrate global processes of adopting and implementing modernist ideas. Still, few attempts have been made to fit the construction of Brasília in the larger history of Brazilian mid-century territorial and industrial development.

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

With this project, I plan to steer the debate on Brasília’s high modernism towards a story of how its builders and residents produced the city as a living space. I will focus on the tangled relationship between the built and natural environments in the city, its surrounding areas, and the broader Brazilian central savannah. Until the 1960s, the region where Brasília was established constituted a vast expanse of high-altitude tropical savannah known as Cerrado. Brasília was the first sizable urban center established in such an environment and, as the national capital, a bridgehead for the occupation of this hinterland. Today, the Cerrado is at the center of Brazilian agribusiness. The establishment of Brasília was crucial to transforming the Cerrado into a landscape of production.

Tom Johnson

Project: The Reckoners: Economic Life in a Fifteenth Century Fishing Village

Tom Johnson is a senior lecturer in late medieval history at the University of York. Before joining the History Department at York in 2016, Tom did his doctoral work at Birkbeck, University of London and held a research fellowship at the University of Cambridge. In 2018–19, he was a Fellow at the Davis Center for Historical Studies at Princeton University. Tom’s research explores the lives of ordinary people during the Middle Ages, with a focus on how institutions shaped social relations. His first book, Law in Common: Legal Cultures in Late-Medieval England (2020) explores the way that legal ideas were used in everyday life in fifteenth-century England.

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions that you are considering?

I first came across the archive from Walberswick over a decade ago, drawn in by its closeness to home—it is kept in Ipswich, where I grew up and where my parents still live—and by the extraordinary array of material that had survived to document the everyday life of a medieval fishing village. I knew from the beginning that it would make a great “microhistory,” and much of the documentation, moreover, consisted of financial accounts, so it was a natural fit for questions I was beginning to consider, about how economic value was conceived of, and how this changed during the later Middle Ages. The fifteenth century has long been understood as a time of major economic transformation, and my hope is that a microhistory can illuminate what that meant for the people who lived through it.

In the course of your research have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

Confronted with a body of financial evidence, my instinct was to insert it into a spreadsheet. I compiled a massive database from one book, recording the numbers of herring and sprats caught by the fishermen of Walberswick between 1450 and 1500, and employed a research assistant to help me process the data. So I know, now, that they caught over 10 million fish in those fifty years!

But more importantly, seeing the disparities between the accounts and the spreadsheet, and the lacunae the transcription created also made me realize the limits of quantification—or more specifically, that the churchwardens making these accounts thought about quantification in different ways to me: not only as a dry process of calculation, but also a social, and in some ways aesthetic process of meaning-making.

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

I hope the book will do a few things. First, that it will illuminate everyday economic life in the later Middle Ages. We know a lot about economic institutions—markets, high-level trade, money, and so on—but rather less about what day-to-day exchange looked like. Second, I want to bring to life how this worked in a rural coastal location in particular; fishing villages are generally under-represented in medieval social history, and I hope the book will help to remedy that. Third and most broadly, I hope that it will contribute to, and build on recent work in the history of medieval economic cultures; specifically, I want to draw more attention to the role of accounting, calculation, and numeracy as everyday practices that allowed ordinary people to make sense of their lives.

Stella Nair

Project: Inca Architecture: Chapters in the History of a (Gendered) Profession

Stella Nair is associate professor of art history at the University of California, Los Angeles and core faculty in the American Indian Studies Interdepartmental Program and the Archaeology Interdepartmental Program. She is also a Senior Fellow of Pre-Columbian Studies at Dumbarton Oaks (Harvard University). Trained as an architect and architectural historian, Nair’s scholarship focuses on the built environment of indigenous communities in the Americas and is shaped by her interests in gender, spatial theory, construction technology, landscape transformations, and hemispheric networks. She has conducted fieldwork in Bolivia, Mexico, Peru, and the United States, with ongoing projects in the South Central Andes. Her current book project, Inca Architecture: Chapters in the History of a (Gendered) Profession, offers new perspectives on the Inca built environment by highlighting the profound ways in which women designed, constructed, used, and gave meaning to Inca spaces and places.

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions that you are considering?

I have spent over two decades working on Andean built environments, including that of the Inca. In recent years, it has become clear to me that Inca architectural studies is based on the assumption that Inca architecture was almost entirely a male enterprise. When most people think about Inca architecture, they think of male patrons, designers, builders, and users. But this goes against Andean traditions, where most activities are undertaken in gendered pairs. Hence, I am asking what roles did women have in the making of the Inca built environment? And, why have we denied the critical role these women played in making and using one of the most magnificent architectural traditions in the world?

In the course of your research have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

I have been surprised by, not the absence, but the presence of ample evidence regarding the diverse roles that women played in shaping the Inca built environment. Even more surprising is that this evidence has not been explored before. I think this says a lot, not only about problems with how we have looked at Inca and other indigenous architectural traditions, but also about the assumption we make about the history of architecture in general. Women have played key roles throughout history in making the built environment, but their roles have often been marginalized when histories are written. I have been surprised to learn how often this has happened.

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

My hope is that 1) we see Inca architecture in a far more nuanced and complex way, and 2) appreciate the critical and varied ways that women contributed to this incredible built environment. The Inca created one of the most sophisticated architectural traditions in the world, yet we have only begun to appreciate its diverse and dynamic history, as well as the key role females played in its making and meaning. I also hope that by highlighting the prominent and pervasive ways in which women shaped Inca places, that future scholars “see” Inca women in the archaeological record (i.e. not just when finding them doing what is currently assumed to be “women’s things” like cooking and weaving).