In this issue we highlight the research of Fellows from the class of 2021–22 who are exploring how forms of personal and public expression have been used to create touchpoints that allow us to situate ourselves within the context of the world around us.

Juan G. Ramos

College of the Holy Cross

Brenna M. Munro

University of Miami

Julia L. Shear

American School of Classical Studies at Athens

Juan G. Ramos

Project: Andean Modernismos: Affective Forms in Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru

Juan G. Ramos is an associate professor in the Spanish Department and former director of the Latin American, Latinx, and Caribbean Studies Program at the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts. He works in the fields of nineteenth-, twentieth-, and twenty-first-century Latin American literature. One of his lines of research has focused on literary and cultural production from Latin America and how it intersects with aesthetics, politics, and decolonial theories. Another line of research focuses more specifically on the Andes and zooms in on the late decades of the nineteenth century and the early decades of the twentieth century to explore questions related to modernismo and the historical avant-gardes.

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions that you are considering?

My first book project Sensing Decolonial Aesthetics in Latin American Arts (2018) examined poetry, music, and film from the long decade of the 1960s in Latin America. As I worked on that project, my attention also turned to literary production in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in the Andean region. I became interested in understanding why scholarship on literary modernism has overlooked writers from Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia. In my current book project, the Andes becomes both a geographical and a cultural concept that enables me to argue that modernism in the Andes and across Latin America was not just about socially or politically disengaged poetry or literature as dominant accounts still maintain.

In the course of your research have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

In studying writers such as Manuel González Prada, Alcides Arguedas, Guillermo Valencia, Gonzalo Zaldumbide, and Aurora Cáceres, among others, it has become quite clear that there was a lot of echoes and shared concerns among authors writing from and about the Andes from the 1880s through the 1930s. Some of these writers were grappling with the role of indigenous populations and women’s rights, while others were shaping public opinion about forming a shared sense of national pride and identity in the aftermath of territorial disputes and wars with neighboring countries. Contrary to long standing views, my argument is that modernist writers employed various literary genres—fiction, poetry, essays, literary criticism, and translation—to intervene in social and political concerns at both the national and regional levels.

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

While my book project is in direct dialogue with Latin American literary studies, my intervention is also informed by Andean studies, theoretical concepts coming from Affect studies, and methodological ideas coming from New Modernist studies. My hope is that this book project will bring renewed attention to a host of authors and archives that are understudied both in English and Spanish. It also seeks to place Latin American literary and New Modernist Studies in English in conversation with each other with the aim that they might mutually enrich and expand the types of questions being asked, as well as the objects of study. Ultimately, by focusing on a region (the Andes), this study draws attention to the critical possibilities that emerge when pursuing a comparative study, rather than using the nation-state as a unit of humanistic inquiry.

Brenna M. Munro

Project: Queer Writing in Digital Times: The Mobile Nigerian Present

Brenna M. Munro is associate professor of English at the University of Miami. Her work operates at the intersection of queer studies and African literature. Her research and teaching explore global queer literature and film, refugee writing and politics, and how digitality shapes and is shaped by the postcolonial literary imagination. While at the National Humanities Center, Munro is working on her second book, Queer Writing in Digital Times: The Mobile Nigerian Present. This book charts the recent literary boom in representations of same-sex loving and gender non-conforming Nigerians across global Nigerian writing, analyzing this turn in relation to two other simultaneous shifts: mass migration and the rise of digital media. The project suggests that in this globally scattered, aesthetically varied archive, to be Nigerian is to be part of a mobile modernity, for which queerness is a key and deeply contested sign.

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions that you are considering?

My starting point was Chris Abani’s astonishing 2004 novel Graceland, which grapples with what it is to be an Igbo boy with a fluid masculinity and sexuality, in a time of globalization. There is now an extraordinary range of Anglophone texts by Nigerians that bring queer people into imaginative life, partly in response to homophobic currents in Nigerian culture and politics, and in lively intertextual conversation with one another. This queer turn has been enabled by a new global Nigerian online literary sphere; so how have digitality, migration, and the writing of queerness shaped one another? What critical language helps us understand texts that are written by domestic, diasporic, and transnational authors—that are mobile, culturally porous, and yet persistently attached to the nation?

In the course of your research have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

I was surprised to find the mobile phone as a resonant presence in these texts, which made me consider this ubiquitous object anew—especially reading Olumide Popoola’s When We Speak of Nothing, a novel about a trans teenager which incorporates text messaging as dialect and epistolary form. The cell phone is a writing and reading machine that has created new forms of language and intimacy: it’s a symbol of modernity, connectedness with other places, social mobility and consumerism; and it also summons up the constant breakdown of these things in precarious everyday life. It’s also a lifeline for migrants. In Nigeria, most people who access the internet do so through phones, not computers; so what does that postcolonial digitality look like?

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

I’d like to see queer literary studies do more comparative work on African literature, not just diasporan literature; and for Africa to be truly part of work on digitality at large. For example, while we are, rightly, in a period of critical dystopianism about digitality, this formation offers a galvanizing counterpoint. While these writers chart the dangers of the internet for queer people in particular, they have made pragmatic, creative use of its affordances—the ability to produce, circulate, curate, and discuss texts without a lot of capital, to create new publics and new forms, and to engage in political struggles like the #EndSARS movement against police violence. These inventive, nuanced negotiations of tech-textuality have a lot to teach us.

Julia L. Shear

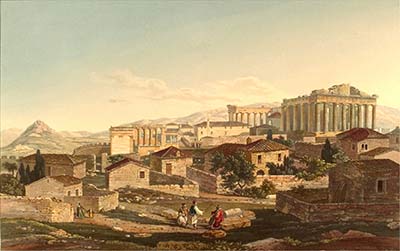

Project: Creating Collective Memories in Ancient Athens

Julia L. Shear is CHS Fellow in Hellenic Studies, Center for Hellenic Studies, Harvard University and Senior Associate Member, American School of Classical Studies at Athens. She works on ancient Athenian social and culture history. She uses both historical evidence and evidence from material culture and epigraphy to provide a holistic picture of ancient Athens and she also applies theories and approaches developed in the social sciences to the ancient Greek material. Another strand of her research focuses on ancient Greek religion, on which she has written a number of articles, as well as her book, Serving Athena: The Festival of the Panathenaia and the Construction of Athenian Identities (Cambridge, 2021). She has also taught at the University of Glasgow and at Boğaziçi University in Istanbul. She has been a frequent member of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, both as a student and as a senior member, and she has held three fellowships there.

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions that you are considering?

After finishing my first book (on how the Athenians remembered and forgot the oligarchic revolutions in the late fifth century BC), I still had lots of ideas about memory buzzing around my head. Eventually, I realised it was enough for another book and, since few people on the classical side were then working on memory, it seemed like a good opportunity. I am asking how the ancient Athenians created collective remembering. So I want to know the processes by which they remembered together, both in the short term and in the longer term. Some of the examples which I am using show collective remembering going on for a long period of time, i.e., several centuries.

In the course of your research have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

Several things about the scholarship have really surprised me this year. When I was working on memory before (i.e., 2007, 2008, and before), there wasn’t that much focused specifically on collective remembering; that really started to change around 2008! So I’ve been surprised at how much the field of memory studies has changed since 2008.

On the classical side, the ‘turn to memory’ suddenly happened for ancient Greece in 2019 and 2020, which I wasn’t expecting. I’ve also been surprised at how undertheorised much of this work is: most of these scholars would really benefit from the kinds of cross fertilisation which takes place regularly at the NHC, although I have to admit that I’m not at all sure that they would take advantage of it, if they were here nor that the NHC would want to support their projects!

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

For the classics side, I want to put collective remembering on a better theoretical footing because that will improve the research being done on remembering in the ancient Greek world. Although collective memory gets invoked quite a bit in the scholarship, no one explains how it works because, I think, they don’t really want to know. I want to show how it worked in our best attested ancient Greek city. It should make comparative work between different cities possible.

For memory studies, despite all the recent work, I still think there is a need to focus on how normal collective remembering worked rather than distoration and problematic cases (inspired by former fellow Barry Schwartz’s observation in the Routledge International Handbook of Memory Studies, pp. 9–10), so I hope my case study will show how it does. Since there’s so little evidence, I really have to think hard about what exactly is going on, while scholars working on other periods and places with much more evidence often don’t do that enough.