This month we highlight the research of Fellows from the class of 2023–24 whose projects look at the immediate and extended social effects of incarceration, resistance in the midst of captivity, and efforts to confront persistent legacies of injustice that resonate to the present day.

Justin T. Clark

Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

Katherine Davies

The University of Texas at Dallas

Devin Fergus

University of Missouri

Lisa A. Lindsay

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Justin T. Clark

Project: The Clockwork Republic: Sociolegal Culture, Time, and Struggle in the United States, 1787–1860

Justin T. Clark is a social and cultural historian of the United States in the long nineteenth century. He is the author of City of Second Sight: Nineteenth-Century Boston and the Making of American Visual Culture (University of North Carolina Press, 2018) and The Zero Season (Penguin Random House, 2022). He has received fellowships from the Huntington Library, the American Antiquarian Society, the Winterthur Library, the New England Regional Fellowship Consortium, the Singapore Ministry of Education, and the Australian National University Humanities Research Centre, among others.

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions that you are considering?

After writing City of Second Sight, I became interested in temporality. I felt that while time consciousness had received significant attention from historians, temporal justice had not. I began to become interested in the connection between temporal justice in “everyday” life and in history; that is, how our understanding of promises in the mundane sense of contracts relates to the promises inherent in American exceptionalism.

In the course of your research have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

In writing an article related to my current book project, I was surprised to discover that 18th-century New England jails were far more dedicated to punishment than historians have generally supposed, in the sense that they tended to hold prisoners at the behest of their putative victims, rather than simply detaining them for trial and other forms of punishment. I’ve also found that debt imprisonment was a much more central part of the development of carceral punishment than historians have generally supposed.

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

I hope it will help us recognize the importance of temporal culture to American history, and in particular, that the problem of time extends well beyond timekeepers, and structures our law and politics. I hope it can also help us understand our present political moment better, by examining how ideas about debts to both past generations and to posterity developed in American consciousness.

Katherine Davies

Project: Care as Custody: A Critical Feminist Phenomenology of the US Foster Care System

Katherine Davies is assistant professor of philosophy at the University of Texas at Dallas, specializing in continental philosophy, feminist and queer theory, and the history of philosophy. She is the author of the forthcoming monograph Heidegger’s Conversations: Toward a Poetic Pedagogy (State University of New York Press). Her articles have appeared in Research in Phenomenology, Arendt Studies, and Epoché: A Journal for the History of Philosophy, among other scholarly venues. Her current research draws upon the recent critical turn in phenomenology as well as feminist and queer studies to interrogate the US foster care system from a philosophical perspective.

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions that you are considering?

Humanities scholars have been studying the foster care system for decades. Yet despite recent advances in ethical and sociopolitical analysis such as mass incarceration studies, critical prison studies, intersectional feminisms, trauma studies, and queer kinship theory, no philosopher has yet brought these resources to a sustained examination of the foster care system. As I have been working, I’ve wondered whether foster care is a welfare system or an arm of mass incarceration, directed primarily against women and children of color. I’ve also considered whether liberal conceptions of subjectivity are sufficient to account for the harms survivors of the system experience or whether feminist relational accounts of the self better illuminate these. Finally, I’ve wondered how survival informs possibilities of queering notions of family and community.

In the course of your research have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

Dorothy Roberts’ work on foster care—which she convincingly shows is better termed the “family policing system”—upended my initial sense of the functionality of foster care. The fact that Black children are removed at four times the rate of white children is both surprising and cannot be ignored. I was reading her book while the Trump administration’s policy of separating families at the southern border was in full effect. The primary tool of this policy is foster care, which has lost hundreds of separated children. When I began working on this topic, I believed I would harness feminist care ethics to argue for trauma-informed practices of caring for vulnerable children. Increasingly, I have come to realize how histories of state violence have shaped foster care.

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

In the extant scholarship on the topic, historical or literary illustration of foster care is often punctuated by quantitative, statistical research or by individual anecdotes of those impacted by the foster care system in some way. A feminist, critical phenomenological philosophical analysis will go beyond these approaches by describing the inherent relationality of the subject with her world as well as the shared features of lived experience that the foster care system molds and shapes. The project aims to both diagnose foster care’s failures in re-traumatizing vulnerable families and communities while also elucidating the particular form of consciousness that results from surviving the system, especially the insight such lived experience can offer for imagining more equitable and just futures.

Devin Fergus

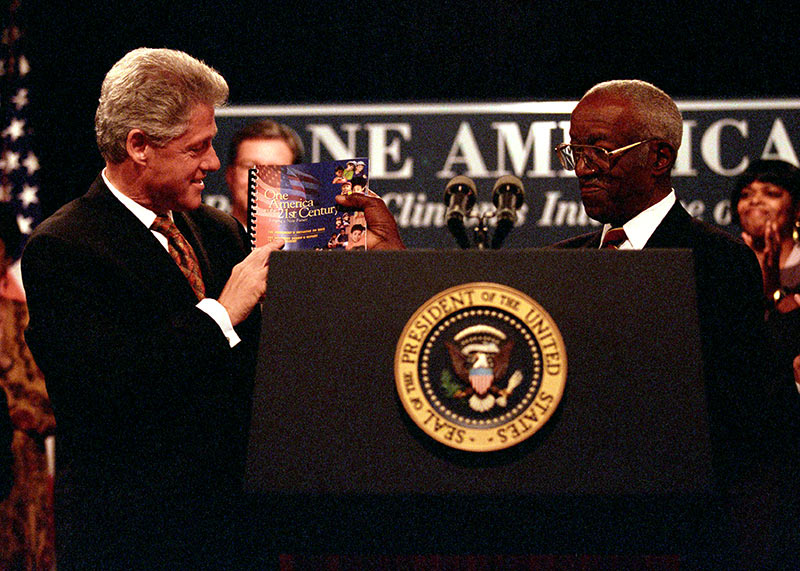

Project: The Making and Unmaking of One America: President Clinton’s Initiative on Race

Devin Fergus is the Arvarh E. Strickland Distinguished Professor of History and Black Studies at the University of Missouri where he teaches in the departments of History and Black Studies, the Truman School of Government and Public Affairs, and the Trulaske College of Business. His writing has appeared in the New York Times, Washington Post, The Guardian, and Slate, among other outlets. He is the author of Land of the Fee (Oxford University Press, 2018), which The Nation designated one of the five most important books by a scholar for understanding capitalism. His first book, Liberalism, Black Power, and the Making of American Politics (University of Georgia Press, 2009), was named a Choice Outstanding Academic Book. At the National Humanities Center, Professor Fergus will complete an in-depth exploration of Clinton’s One America (1997–98): A Presidential Initiative on Race (PIR), which was the last major federal initiative to address racial reconciliation and racial equity.

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions that you are considering?

The origin story of this project dates to the last national effort to systematically grapple with race in America—Clinton’s Presidential Initiative on Race (PIR). With the post-Cold War as backdrop, the initiative was intended to provide the nation with a racial roadmap for the 21st century in order “to become the world’s first truly multiracial, multiethnic democracy.” Yet, as we approach the quarter century mark since the PIR’s 1998 report, the US has seemingly veered far off the path hoped for and envisioned by Initiative architects. What might the making and unmaking of One America tell us about race and American democracy in the 21st century?

In the course of your research, have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

I am fortunate to be coauthoring this project with Dr. Nishani Frazier, associate professor of American studies and history at the University of Kansas. Dr. Frazier is a consummate researcher and scholar. In the personal papers of Dr. John Hope Franklin, Dr. Frazier located a letter that I wrote when I was a graduate student and shortly after Dr. Franklin finished his term as PIR chair. The letter shows the profound influence that he had on my approach to history then and now. I was genuinely surprised by Dr. Frazier unearthing my letter. It was a time capsule into my much earlier thinking as a fledgling professional historian that Dr. Franklin’s work on the PIR was crucially important to race relations in America.

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

The events of this summer, most notably the Supreme Court’s opinions considering race in higher education admissions, has returned us to a familiar inquiry: whether race and diversity remain compelling state interests. The color-blind agenda of the court today echoes the political environment that drowned out the most important of PIR’s findings. For all its flaws and shortcomings, PIR interpreted race and diversity as not simply part of the nation’s past but necessarily constitutive to America’s future—that is, a public good that would advance the national interest now and into the 21st century, within and beyond the US borders.

Lisa A. Lindsay

Project: “Unity”: African Women and Resistance in the Atlantic Slave Trade

Lisa A. Lindsay is professor and recent former chair of the Department of History at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. A specialist in the history of Nigeria, the slave trade, and the Atlantic world, she is the author of Atlantic Bonds: A Nineteenth Century Odyssey from America to Africa, which won the African Studies Association’s prize for the best book in any field of African studies published in 2017, as well as additional books and coedited volumes on African and diaspora social history. She has won fellowships from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the American Council of Learned Societies, the National Humanities Center, and the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation; and her outstanding teaching has been recognized with a UNC distinguished term professorship.

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions that you are considering?

How did the Atlantic slave trade transform the lives of West African women? I was already interested in this question when I encountered the captain’s log of the slave ship Unity, which sailed from Ouidah (in modern Benin) to Jamaica in 1770. The ship contained a large number of enslaved women, who repeatedly resisted their captivity. My goal is to narrate and contextualize this voyage to help illuminate how overseas slaving transformed relations between men and women in African societies, how African women became enslaved, what they experienced as captives, and how they resisted. To probe these topics is to better understand gender and human trafficking in the Atlantic world and perhaps to inspire solutions to what seem like intractable problems today.

In the course of your research have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

Several elements of the voyage of the Unity are surprising. Compared to other slave ships, it included a large proportion of female captives. Its prisoners rose in revolt, not once, not just in sight of land, but on multiple occasions. The resistance seems correlated with deaths from smallpox, which was understood in Dahomey as a weapon of Sakpata, the deity of smallpox and political opposition. Finally, at the same time that the Unity sailed, other ships from the Bight of Benin carried large numbers of enslaved women, who also rebelled. The cluster of disproportionately female, disproportionately defiant slave ships from this time and place points to specific forces leading to the enslavement of women, their familiarity with violence, and their determination to fight.

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

Scholars have described African responses to European demand for enslaved labor and the experiences of enslaved women in the Americas, but we have much to learn about the slave trade’s profoundly gendered effects on African societies. How did Atlantic slaving affect women in Africa? How were women enslaved? How did female captives confront and endure the Middle Passage? How did women shape insurrections? By investigating enslaved African women’s experiences and actions, we can more fully envision resistance to slavery, beginning in West Africa and flowing across the Atlantic. In our own time, Unity serves as a reminder of women’s centrality to world-shaping processes, their resilience, and their power to challenge seemingly insurmountable forces in pursuit of a more secure future.