This month we highlight the research of 2025–26 Fellows whose projects examine the ways communities (created through proximity or shared experience) are formed and transformed in response to crisis.

Asa Eger

University of North Carolina at Greensboro

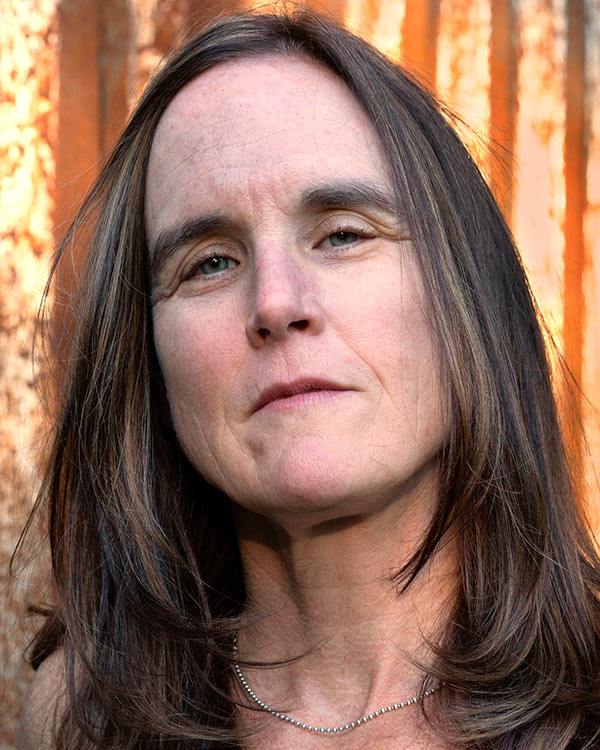

Grace Elizabeth Hale

University of Virginia

Patrick McKelvey

University of Notre Dame

Asa Eger

Project: Erased Archaeology: The 19th/20th Century Settlement of Bosnians at Caesarea, Israel

Asa Eger is a professor of the Islamic world in the Department of History and the Program in Archaeology at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Since 1996 he has been conducting surveys and excavations in Anatolia and Syria-Palestine (the Levant) from the Byzantine period through the Late Islamic period. He focuses on frontiers, landscape archaeology, and environmental history, as well as urbanism and the relationship between cities and their hinterlands. He also specializes in ceramic material culture. He has conducted surveys and excavations in Turkey, Greece, and Cyprus and currently is codirector of the Caesarea Coastal Archaeological Project in Israel since 2022. His project’s main research objective is to investigate the transformation of Caesarea from the classical city to the later medieval (seventh–thirteenth centuries, early and middle Islamic/Crusader periods) and modern town (1880–present).

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions that you are considering?

As I was assembling early images of the site of Caesarea in Israel, I came across a 1917 German aerial photograph which showed its Crusader walls, and within houses set within land plots. Growing up near the site, I had always been told that it was abandoned after the Crusader period, save for a refugee camp of relocated Bosnians squatting in the ruins. Looking at the photograph, however, revealed a small organized town. The town lasted 70 years, from 1880 to 1948. This led to several questions: What is the archaeology of nineteenth- and twentieth-century Palestine and why has it been ignored in modern-day Israel? What different methods can we use to tell the story of this settlement beyond excavation, such as oral histories, photographs, registers, and public history? Can this be a model for addressing deep conflicts through education and public outreach?

In the course of your research, have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

The Bosnian settlement has been described sporadically and only as a refugee camp of squatters living amidst ruins, but this is a false narrative. Excavation of one house has shown a multi-story well-built stone structure with a basement filled with imported luxury porcelains and other pottery from England, France, Germany, the Aegean, Constantinople, China and Japan, as well as liquor bottles from New York, roof tiles from Marseille, and British electric switches. And this is just one house and what was left behind when a family was forced to leave and the house was bulldozed. The material culture of this settlement, when given attention, easily shows a well-established and well-built town, not poor but with some means, and connected globally.

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

It is past time for the archaeology of the modern period to be considered part of Islamic archaeology. This is particularly the case in countries like Israel, where the various recent pasts, whether under Turkish Ottoman control or British colonial control, are viewed with incredible difficulty, and an urge to rewrite and establish a new narrative in step with national ideologies becomes part of the agenda of the nation-state. Archaeology, as a study of an assemblage of a physical past based on material culture, has the ability to address these difficult pasts by overriding constructed national narratives and create conversations between groups and educate. This is particularly the case now in Israel and Palestine as we witness so much misinformation and violent claims to land that are seemingly irreconcilable.

Grace Elizabeth Hale

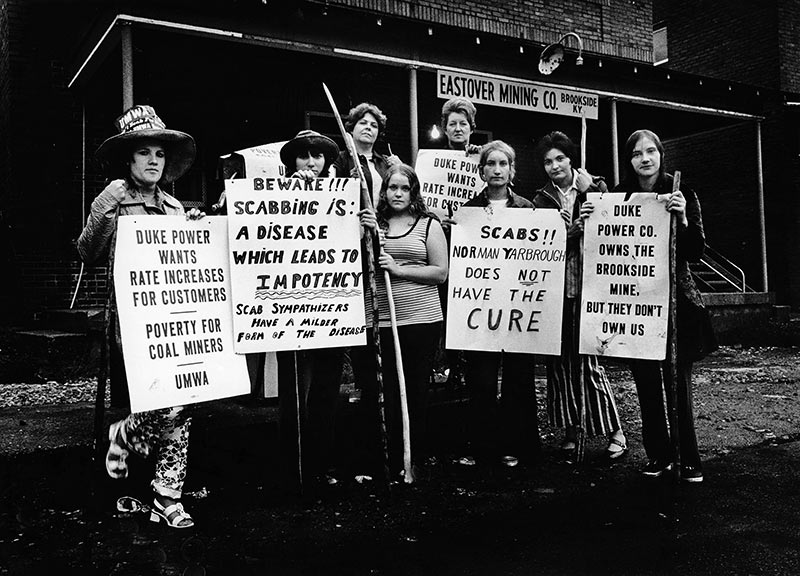

Project: They Don’t Own Us: Harlan County, Kentucky and the Fight for the Future of the American Working Class

Grace Elizabeth Hale is the Commonwealth Professor of American Studies and History at the University of Virginia. She writes about the history of twentieth-century America and the regional culture of the South for both academic and general audiences. Her most recent research has focused on uncovering untold and forgotten stories of the rural and small-town South. Her current project, They Don’t Own Us: Harlan County, Kentucky and the Past and Future of Working Class America, tells the dramatic story of the first strike in US history to successfully adopt the tactics of the 1960s social movements and what it reveals about the forgotten history of labor’s fight to save the American Dream in the 1970s.

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions that you are considering?

Earlier in my career, I researched how scholars and artists used film, audio recordings, and photography to document changes in the South during the 1960s and 1970s. That work led me to Barbara Kopple’s Harlan County USA, a brilliant and confusing film about a 1973–74 coal strike. My book, They Don’t Own Us: Harlan County, Kentucky and the Past and Future of Working Class America, tells the full story of this victorious strike for the first time: how locals mobilized an entire Appalachian community, and a newly democratized United Mine Workers of America invented a new kind of labor organizing to make the strike a national issue. I reveal what the fight against the economic and political changes we now call neoliberalism looked like from the perspective of working-class Americans who did not know our world would be their future.

In the course of your research, have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

I learned that union records can read like a screenplay. When the Miners for Democracy (MFD) reform movement took over the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) at the end of 1972, a group of idealistic young MFD staffers went to work for the union. The strike memos they wrote are full of compelling big-picture narrative arcs, complete scenes, and visual and even gossipy details. One former staffer, a retired labor lawyer, told me those records were a major problem because the union was constantly sued by coal operators. After his work for the UMWA, he never let any other union he worked for keep those kind of detailed records again.

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

I hope my book reminds both general readers and humanities scholars of one of the most forgotten aspects of recent American history: the labor militancy of the late 1960s and 1970s. In that period, union members and New Left and civil rights activists worked with some success to create a nationwide, class-based political alliance that they hoped would serve as the foundation for a progressive majority. Globalization became the rallying cry of their opponents, an attack on the political and economic power of American workers disguised as a way of helping consumers. Today, as the neoliberal order constructed out of this labor coalition’s ultimate defeat unravels, it is worth asking what we could have had instead and still might achieve.

Patrick McKelvey

Project: Supporting Actors: A Disability History of Theatrical Welfare

Patrick McKelvey is an associate professor of film, television, and theatre at the University of Notre Dame. He researches the cultural, social, and theatrical history of disability in the twentieth-century United States. His first book, Disability Works: Performance After Rehabilitation (New York University Press, 2024) received the Working-Class Studies Association’s CLR James Award and was a finalist for the Association of American Publishers’ PROSE Award (Music and the Performing Arts Category). His other writings appear in Theatre Journal, Theatre Survey, and Journal of Dramatic Theory and Criticism. With the support of a 2025–26 National Humanities Center fellowship, McKelvey is writing a second book, Supporting Actors: A Disability History of Theatrical Welfare.

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions that you are considering?

A key figure in my first book, Ron Whyte, frequently availed himself of emergency relief funding from organizations like the Actors Fund of America, a voluntary organization founded to alleviate poverty in the industry. Reading Whyte’s requests for relief alerted me to a disability history of American theatre hiding in plain sight. Whyte identified as disabled and engaged in disability artistry and activism, but this is not what made him eligible for aid: his economic disenfranchisement related to his impairment did. Organizations like the Actors Fund and the services they provide offer the opportunity to tell a new kind of story about the role of disability in American theatre history. How might exploring these organizations make it possible to tell a history that doesn’t assume disability is only ever at the profession’s margins?

In the course of your research, have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

Right now I’m focusing on writing three chapters about social services for theatre workers with HIV/AIDS. As you can imagine, the research for each of these chapters has had its surprises. In writing the introduction, I’ve been surprised about how closely conversations in theatre and performance studies about “events” versus “infrastructures” resemble conversations in AIDS historiography about “activism” versus “service provision.” In researching the first of the two body chapters on the Actors Fund’s AIDS Initiative, I have been struck by how consistently and how thoroughly the Fund institutionalized norms, practices, and services as they were first offered at Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC). I’ve also been stunned about how HIV/AIDS shaped the history of the Fund. (I’ll leave it there for now—no spoilers!).

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

At the same time that I’m interested in telling a story that hasn’t been told before, I’m interested in the book being methodologically useful for theatre and performance scholars of all stripes. My hope is that it not only makes the case for why we need to think about infrastructures that sustain performance, but that it might model how to do so. This requires disability being part of the picture. I’m part of a larger cohort of scholars asking questions about arts, institutions, and support–and my hope is that Supporting Actors can demonstrate why arts research on infrastructure needs disability history, theory, politics, and activism to be part of the conversation. I’ll have done my job if Supporting Actors helps bring disability closer to the center of theatre and performance research.