This month we highlight the research of 2025–26 Fellows whose projects raise questions about how we categorize and interpret constructed objects—ships, buildings, and works of art. Further, they ask what can be gained by viewing these creations (and their creators) through a different lens.

Christy Anderson

University of Toronto

Alison L. Beringer

Montclair State University

Jiren Fing

University of Hawaiʻi at Hilo

Christy Anderson

Project: Castles of the Sea

Christy Anderson is a historian of architecture whose work bridges early modern Europe, global maritime history, and contemporary design. A professor in the Department of Art History and member of the Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape, and Design at the University of Toronto, she is particularly interested in how architectural knowledge moves across cultures, materials, and environments. Her current book project explores the ship as an architectural type—examining how mobile spaces at sea have shaped cities, labor, and natural landscapes across the Atlantic world. Anderson is the former editor-in-chief of The Art Bulletin, where she championed scholarship that expanded the field’s boundaries in time, geography, and method. Her broader commitment to public-facing humanities includes collaborative digital platforms, podcasts, and curatorial projects that engage diverse audiences in the interpretation of architectural and material histories.

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions you are considering?

The project began with a realization that my history of Renaissance architecture [OUP 2013] described buildings that stood still, though the world they belonged to was in motion. I wanted to ask how architecture might be reimagined through movement—through ships, ports, and ropewalks that joined land and sea. The spark was also personal: I grew up around boats and recognized their textures, sounds, and rituals as forms of knowledge. This project asks how ships can be understood as architecture—structures that organized labor and embodied technology—and how histories of motion might expand architectural history itself.

In the course of your research, have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

What surprised me most was how consistently boats were understood to embody people, virtues, and nations. In early modern sources, ships were not just tools of navigation but extensions of the self and the state—figures of character, faith, and ambition. Captains described their vessels as living bodies; monuments and epitaphs praised men as if they had “made themselves ships.” This conflation of person and vessel revealed how maritime architecture carried moral and political meaning, turning the ship into both an instrument of empire and a portrait of identity.

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

I hope this work will encourage scholars to think about ships as buildings—mobile, often fragile structures that nonetheless share the materials, techniques, and spatial logics of architecture on land. Seeing ships as architecture opens new ways to connect maritime and terrestrial histories: to trace how forests, fields, and ports were linked through craft, labor, and design. More broadly, it invites an expanded architectural history that includes motion, instability, and maintenance as central conditions of the built world.

Alison L. Beringer

Project: Virgil as Sculptor: Premodern Literary Perceptions of the Art of Sculpting

Alison L. Beringer is an associate professor of classics and humanities at Montclair State University. Trained as a German medievalist (PhD, Princeton University), and with an undergraduate degree in classics and comparative literature, Beringer pursues research in the Nachleben of antiquity in medieval and early modern Germany. She is particularly interested in the interactions between the visual and the verbal—ranging from relationships between illuminations and texts in medieval manuscripts to literary narratives about visual artifacts, both aspects that underlie her book The Sight of Semiramis: Late Medieval and Early Modern Narratives of the Babylonian Queen (Arizona Centre for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2016). Beringer also regularly teaches about issues of gender and representation in medieval culture, and was coeditor of the collection Gender Bonds, Gender Binds: Men, Women, and Family in Middle High German Literature (2021).

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions you are considering?

I am interested in the adaptation of ancient material. While working on my first book, which explored the medieval and early modern Nachleben of the Babylonian Queen Semiramis, I came across a sixteenth-century German Meisterlied (song) that adapted a story about a statue of her. Singing about a statue fascinated me: both media memorialize but in different ways. Investigating the vast corpus of Meisterlieder, I found other songs treating statues or sculptors, including one about the poet Virgil as a sculpting magician. Questions of why stories about statues held such appeal, of how statues signify, of what it might mean for real sculptors that the magician Virgil is practicing their art, and of distinctions between religious and secular statues, all against the backdrop of contemporary theoretical debates about images, inform my project.

In the course of your research, have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

Early modern depictions of the Roman artist Marcia show her as both sculptor and painter, a combination virtually without precedent in the German literary tradition. A subsequent foray into the iconography of Marcia has led to critical insights for my work.

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

The thousands of Meisterlieder on a wide range of topics offer an avenue into the non-elite production of literature. For my purposes in this project, these songs offer snapshots of late medieval and early modern reception of antiquity as well as responses to contemporary events and beliefs and serve as fertile starting points for research and for discussion material in the classroom.

Jiren Feng

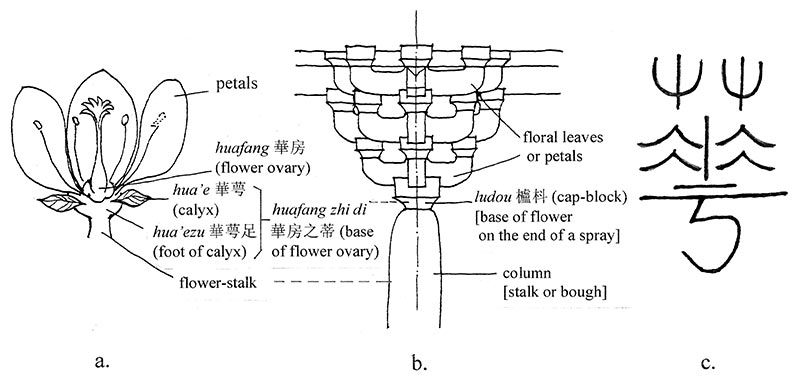

Project: The Imperial Song (960–1279) Architectural Culture: Ritual Order, Political Demand, and Religious Concerns

Jiren Feng is a professor of Chinese studies at University of Hawai’i at Hilo. As a scholar of Chinese art and architectural history, he received academic training both in China and in the West. His recent research interests are focused on the interplay between architecture, literature, language, and society, as well as cultural studies of classical texts on architecture. He is the author of Chinese Architecture and Metaphor: Song Culture in the Yingzao Fashi Building Manual (University of Hawaii Press and Hong Kong University Press, 2012), which received the “International Book Prize Reading Committee Publishers Accolade for Outstanding Production Values–Humanities” at the International Convention of Asian Scholars Biennial Book Prize 2013 Competition in Macau. His other publications in Chinese and English have addressed the subjects of Buddhist architectural art at Mt. Wutai, restoration studies of Dunhuang Grottoes architecture based on Dunhuang documents, Northern Song imperial mausoleums and geomancy (fengshui), archaeological dating of Chinese wood-framed structures, as well as Song-dynasty architectural terminology and conceptualization.

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions you are considering?

The initial spark would be my dissertation proposal at Brown University about twenty-five years ago. I planned to do a comprehensive study of imperial Song architecture, using a synthesized approach that would exploit relevant archaeological, pictorial, and textual evidence. As soon as I began writing the first chapter, which was on the imperial building standards Yingzao Fashi, I found myself having so much to say about the fascinating cultural factors discovered from this text. As it turned out, my research on it became my final dissertation and later my first book, Chinese Architecture and Metaphor. In the meantime, I have been continuing what I initially planned: the first comprehensive study of imperial architectural culture in Song China, questioning how the ritual order, political demands, and religious concerns impacted upon it.

In the course of your research, have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

Yes. For instance, my research on imperial Song mausoleums has included a reconstruction of some important buildings based on my in-depth reading of contemporary texts, such as the two side halls at the end of the stone statues and the Sacrificial Hall in front of the tumulus. Local archaeologists had followed my research and successfully identified the remains of the two side halls, but were unable to find the remains of the Sacrificial Hall in their first archaeological excavation. I was surprised, but I never doubted its actual existence. Happily, years later, the director of the provincial archaeological team reassured me that they did a second-round excavation using smaller square units of exploration than before, and they had found the remains of Sacrificial Hall exactly in front of the tumulus of an empress’ mausoleum!

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

My previous research on the imperial Song architectural treatise Yingzao Fashi (Building Standards) has demonstrated that a new approach would be needed in the study of this text, which suggests reading it as a special literary work and paying attention to the socio-cultural factors behind the lines of technical content. Extending my study from this text to all aspects of imperial architecture, including palaces, imperial gardens, mausoleums, ritual architecture, and religious architecture under imperial patronages, my research project at NHC will continue to interrogate relevant literary records, physical evidence, and pictorial materials. I hope it will prompt new avenues of inquiry by linking the architecture to its historical and intellectual settings, as well as individuals related to the production of it.