This month we highlight the research of 2024–25 Fellows whose projects examine social groups with shared experiences of the world, based on racial identity or personal ideology, and their capacities to imagine alternative realities.

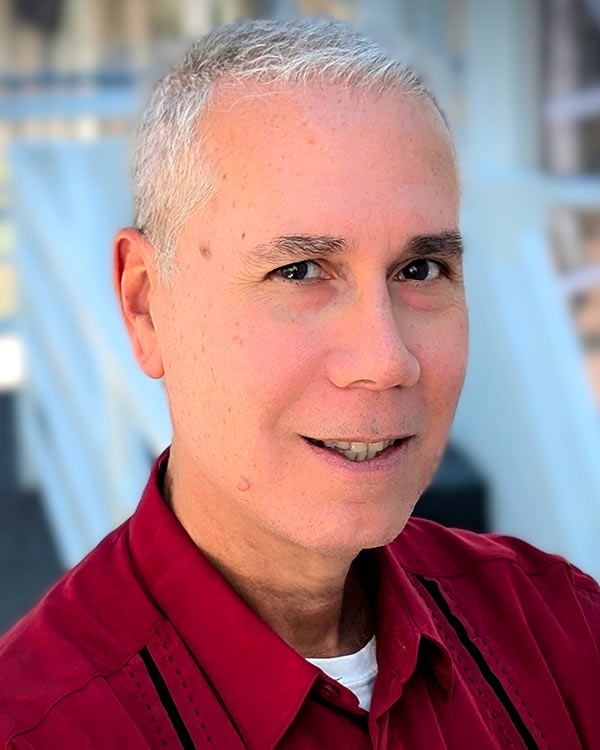

Joseph M. H. Clark

University of Kentucky

Deborah Mauskopf Deliyannis

Indiana University Bloomington

Sarah Scott

Manhattan College

David J. Vázquez

American University

Joseph M. H. Clark

Project: Witchcraft and Contraband in the Early Modern Caribbean

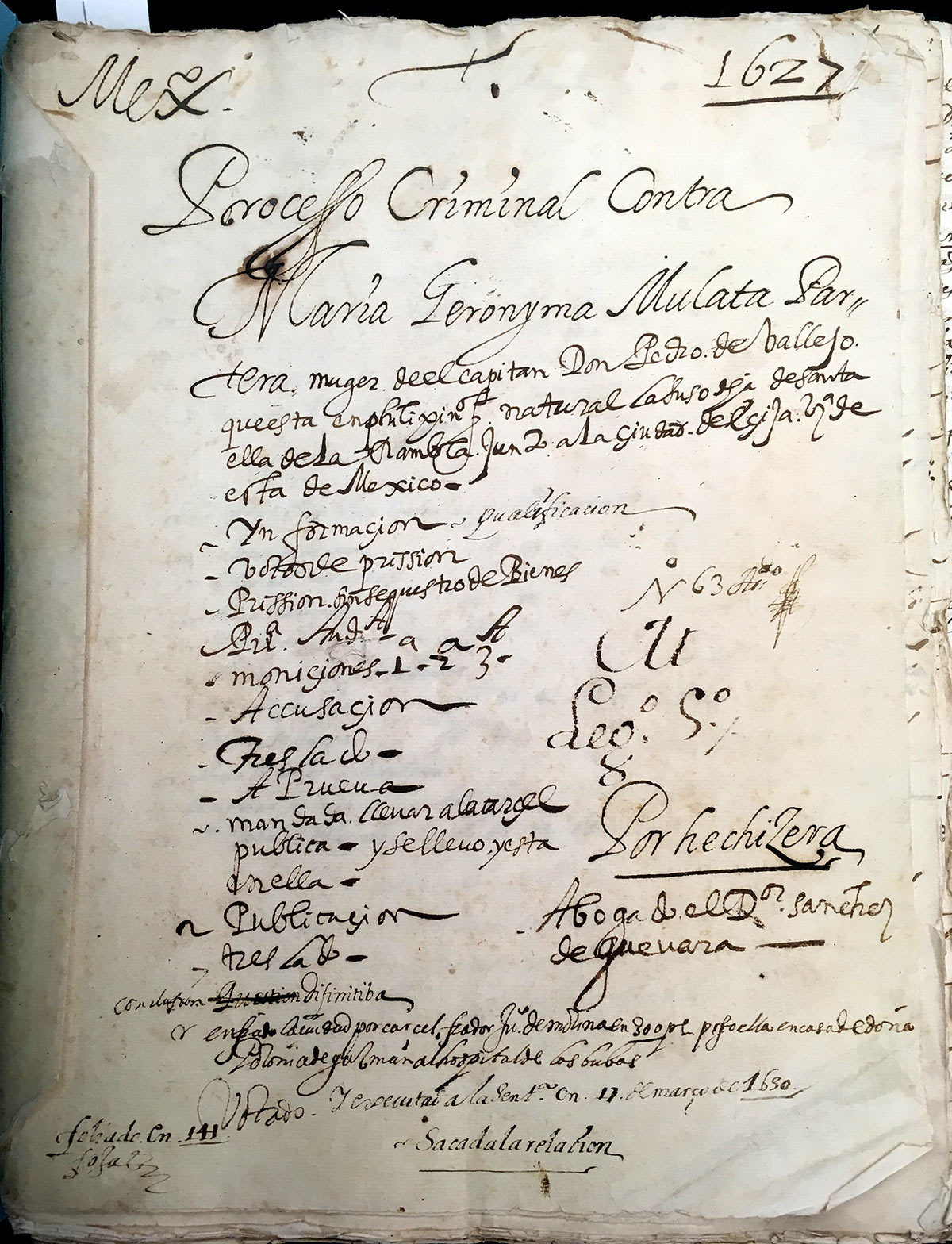

Joseph M. H. Clark is associate professor of history at the University of Kentucky, where he teaches courses on Latin American, Caribbean, and Atlantic History, as well as thematic and global courses on the histories of race, environment, and disaster. A social and cultural historian of the Early Modern Atlantic World, his work is situated at the intersections of commerce, climate, and African diaspora. His first book, Veracruz and the Caribbean in the Seventeenth Century (Cambridge University Press, 2023), examined the Mexican port city of Veracruz, elaborating its material relationships with the Caribbean Islands and the impact of those relationships on the city’s Afro-descended population. His current book project is Witchcraft and Contraband in the Early Modern Caribbean. It examines the relationships between folk healing, spiritual practice, and informal trade in the Caribbean (ca. 1600–1640). The book is especially interested in how Caribbean people adapted the natural world into their spiritual and economic practices in the Early Modern period.

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions that you are considering?

I’ve long been interested in how regular people in the Caribbean built communities outside terms favored by the colonial state. In my first book, I used Inquisition records—especially those concerning free, Afro-descended women accused of witchcraft—to build out otherwise opaque social networks. But I never really considered the links between women accused of witchcraft and contraband trade until later, when I was writing up a “left over” case and it suddenly dawned on me that these cases centered on commerce without naming it explicitly. Not only were inquisitors as concerned with women’s economic independence as they were with superstition, the acts of witchcraft they were accused of usually had to do with controlling or manipulating men who were involved with overseas trade—sailors, merchants, and port officials.

In the course of your research, have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

Everything surprises me! The thing I find most compelling about studying people who lived hundreds of years ago is that, while aspects of their lives are unmistakably similar to those of people today, the world they lived in was entirely different. I’m most surprised when I find stories of regular people doing things—folk rituals, superstitious practices, festival performances—that people still do today (often down to the details). When people did those things 400 years ago, they did not have the same meaning as the same actions have today—but those people 400 years ago were contributing to a creation of meaning that continues to have purchase. As an historian, I focus on what things meant to people at the time, emphasizing discontinuity, but I am continually surprised at how much the (relatively) distant past continues to reverberate.

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

My biggest hope is that my colleagues and I, as a field, will continue to unthink the power dynamics embedded in the archive. Whatever our individual topics, historians of the early modern world face the common problem that the people who wrote things down several centuries ago tended to be people with power and the things they wrote tended to be instruments of that power. We get forced into a false choice of dividing the past into stories of either resistance or victimization, which ultimately limits us to centering the perspective of the powerful. My hope for Witchcraft and Contraband is that by showing the links between informal commercial and spiritual practices, we can begin to think about other ways of looking past the world described by Spanish officials to the communities built and maintained by regular women and men.

Deborah Mauskopf Deliyannis

Project: “To Rival the Temple of Solomon”: Splendid Churches and Bishops in Early Christianity

Deborah Deliyannis is the Donald A. Rogers Professor of History at Indiana University Bloomington. She specializes in the history and material culture of early medieval Europe and the Mediterranean. She earned an undergraduate degree in archaeology and a doctorate in the history of art, but much of her research focuses on the way history was written in the Early Middle Ages, and she has primarily taught in history departments. She has published extensively on the city of Ravenna, Italy, from the fifth to the ninth centuries, including a Latin edition and English translation of the ninth-century author Agnellus’ Liber pontificalis ecclesiae Ravennatis (Book of Pontiffs of the Church of Ravenna), and a general history of the city and its monuments, Ravenna in Late Antiquity (2010). Her most recent book, Fifty Early Medieval Things (2019), is a handbook of early medieval material culture, co-written with Paolo Squatriti and Hendrik Dey.

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions that you are considering?

Since my doctoral dissertation, I’ve been studying a genre of texts known as gesta episcoporum (“deeds of bishops”). These serial biographies of all the bishops of an individual see include extensive descriptions of the splendid churches that the bishops built in their cities. In 1997, I published an article that argued that the model for this genre was the Old Testament descriptions of the Temple of Solomon in the Books of Kings. In the years since, I have wondered why Christians would take this as a model. The big question is, how should rich Christians spend their money? Quite a lot has been written recently about the socio-political implications of giving money to the poor, and almost nothing has been written about the idea that donating money to build a fancy church also became a virtuous act.

In the course of your research, have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

I started with gesta episcoporum, but I was surprised at how widespread the ideology about Solomon’s temple as a model for churches is. Once I started looking, I found it in poems, biographies, saints’ lives, inscriptions, legal documents—literally everywhere. There are also some really interesting cases in which one theologian wrote something about church-building that is quoted by later authors. Clearly the arguments in favor of fancy churches, and the arguments opposed to them, were in dialogue for all the centuries that I am studying (4th–9th), and the most interesting thing about this research is that the question of how Christians should donate their money is still very relevant today.

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

This is actually the first research project I have done that has implications beyond my field! Examining the socio-political-religious circumstances that first led Christians to want to construct elaborate churches, and the theological justifications that were created to accommodate this practice, should lead to consideration of the same issues in other times and places. My discussion of how churches are described in a whole variety of texts, and in particular the fact that the language reflects the aims of the authors and not necessarily what was “actually seen” should lead to a reevaluation of many other textual descriptions of individual churches, and a richer appreciation of the meaning that church building had in the spiritual, social, and cultural life of Christian communities.

Sarah Scott

Project: The Moral Philosophy of Frances Power Cobbe: Forgotten British Philosopher and Women’s Rights and Animal Welfare Activist

Sarah Scott is professor of philosophy at Manhattan College. Her areas of specialization are ethics, the history of philosophy, religious philosophy, and feminist philosophy. She is especially interested in historically marginalized figures and figures that defy current notions of philosophic genre. Scott is the editor of Martin Buber: Creaturely Life and Social Form and is the author of several articles and chapters on Martin Buber. Her current research focuses on women in the history of philosophy. While in residence at the National Humanities Center, she will be working on a book on the moral philosophy of forgotten nineteenth-century philosopher Frances Power Cobbe, exploring her account of women’s rights and animal welfare. This project incorporates material from recent fellowships Scott held working in the Cobbe collection at The Huntington Library and the animal rights and animal welfare collections at the North Carolina State University Libraries.

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions that you are considering?

While progress has been made on the study of early modern and twentieth-century women philosophers, little work has been done on nineteenth-century women. I realized that I would have to write my own article to have something to assign in a class. Upon uncovering the wealth of Cobbe’s work, I realized that this was instead a book project. My research on Cobbe explores questions such as: How do moral concepts get created and taken up in society (e.g., the creation of the concept of an animal right or the evolution of the concept of torture)? How do reason and sympathy inform moral knowledge? What is the best strategy to call attention to moral harms? What do women’s rights and animal welfare have to do with each other? How do people who are unable to access formal education practice philosophy? How and why do prominent philosophers get erased from history?

In the course of your research, have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

Usually doing retrieval work you have to make the case that the marginalized figure was actually important or that they were really a philosopher. In Cobbe’s case the surprise is that she was widely respected as a philosopher, used established philosophical methods and rhetoric, and had a broader readership and impact than most academic philosophers. The question then becomes, why was she erased from history? The origins of the animal welfare movement in theistic Kantian ethics and work by women philosophers have largely been erased from contemporary accounts of practical ethics. This retrieval of Cobbe shakes up the history of philosophy and challenges the standard narrative that women’s rights and animal welfare were the sole purview of utilitarians. However, a sad surprise is how much the moral problems she grappled with still face us today.

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

Periodical writings, pamphlets, and conduct books have been little studied as modes of philosophic writing. They are examples of how subcultures, either blocked from academia, such as women, or opposing establishment practices, such as anti-vivisectionists, can produce rigorous, alternative moral theories that still remain to be explored by current moral philosophers. Cobbe explored why women and animals are seen as “beatable” and as existing outside of moral law. She had to figure out what counts as evidence for moral arguments when patterns of sympathy lead most readers to dismiss the evidence of the suffering of women and animals. All of these problems are ongoing and we can learn as much from Cobbe’s rhetorical tactics as we can from her moral theories.

David J. Vázquez

Project: Days of Futures Past: Latinx Science Fiction and Speculative Futurity

David J. Vázquez is associate professor of critical race, gender, and culture studies and program director of Latina/o/x studies at American University in Washington, DC. His work focuses on the intersections between decolonial environmentalisms, Latinx Studies, and literary and cultural studies. His new work explores the historical resonances of science fiction, including the genre’s explorations of environmental harm, decoloniality, and utopianism. Vázquez is co-editor of the award-winning volume Latinx Environmentalisms: Place, Justice, and the Decolonial (Temple, 2019) and the author of Triangulations: Narrative Strategies for Navigating Latino Identity (Minnesota, 2011). In addition to his current affiliations, he is a former director of the Center for Latina/o and Latin American Studies at the University of Oregon and a past fellow at the Institute for Humanities Research at Arizona State University and at the Oregon Humanities Center at the University of Oregon. His new book, titled Decolonial Environmentalisms: Race, Genre, and Latinx Culture is in production with the University of Texas Press.

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions that you are considering?

I wrote a chapter on science fiction in my current book project, Decolonial Environmentalisms: Climate Justice and Speculative Futures in Latinx Cultural Production. That chapter focused on Alex Rivera’s film Sleep Dealer and Sabrina Vourvoulias’s novel Ink. But as I wrapped up the writing for that chapter, I realized that I had a lot more to say about science fiction and futurity. I realized that part of what excites me about sci-fi is the fact that, to gloss novelist Frank Herbert, sci-fi is never about the future. It’s about the present and often about the past. This got me thinking about how much Latinx sci-fi engages in projects designed to make visible occluded pasts and/or help readers/viewers to pay attention to the trajectories our present realities determine, or what I’m calling sedimented histories within Latinx sci-fi.

In the course of your research, have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

I’m surprised by the consistency of sedimented histories in Latinx sci-fi and how science fiction in general engages in “recovery projects.” I realized that if I really wanted to write about science fiction, I would have to go back and read some of the classic texts. What I found is that texts like Wells’s “The Time Machine” or Huxley’s Brave New World often engage in projects of historical reckoning. What makes Latinx sci-fi interesting, though, are the specific histories the creators I consider seek to excavate. They’re not just interested in thinking about the relationship between past, present, and future, but also about reclaiming and making visible occluded (and oftentimes actively subverted) histories: the histories of colonialism in the New World or the projects of racism and anti-immigrant sentiment that we deny as a society.

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

What was once a field dominated by realistic texts and ideas is now one where sci-fi is one of the (if not the) dominant strains of cultural creation. Yet critical engagement with these texts, works of visual art, and films has lagged behind other forms of cultural analysis. My study aims to take on this burgeoning canon of Latinx sci-fi as works of science fiction. In doing so, my work strives to provide a critical lens that allows readers and viewers to consider how Latinx sci-fi engages with occluded and denied histories of colonialism, racism, and anti-immigrant sentiment. This project also foregrounds the utopian strains in Latinx sci-fi in order to make visible the hopeful ways these authors and artists imagine the future. It is simply the case that these creators have a vested interest in imagining a more hopeful future.