This month we highlight the research of 2025–26 Fellows whose projects examine how media technologies—printing, typography, and sonic archives—have been harnessed and adapted to reflect distinctive identities, preserve cultural elements or memories, and help foster community.

Alejandra Bronfman

University at Albany

CJ Jones

University of Notre Dame

Young Kyun Oh

Arizona State University

Alejandra Bronfman

Project Title: Afterlives of a Voice: History and Memory in Sonic Archives

Alejandra Bronfman is a professor of Caribbean studies at the University at Albany. She is a historian of media and the Caribbean with particular interests in networks of knowledge production, cultural practices, and imperial legacies. Her first book, Measures of Equality: Race, Citizenship and Social Science in Cuba, 1902–1940 (The University of North Carolina Press, 2004) examined the relationship between race, social science, and black activism in early twentieth-century Cuba. A regional and entangled understanding of the Caribbean framed two subsequent monographs, On the Move: The Caribbean Since 1989 (Zed Books, 2007), and Isles of Noise: Sonic Media in the Caribbean (The University of North Carolina Press, 2016). Her current interest in sound and media grew out of the recognition of their simultaneous centrality and invisibility in Caribbean historiography.

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions you are considering?

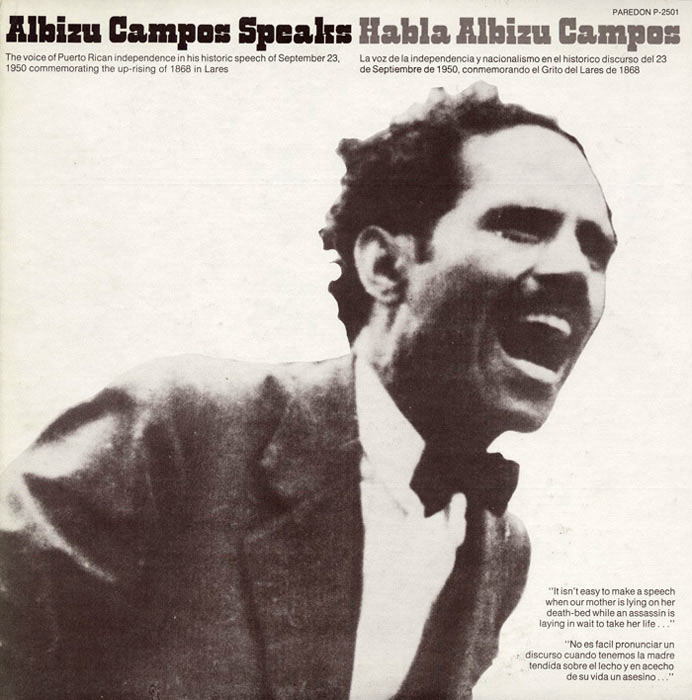

My project is on the ways recorded sound produces and reconfigures collective memories. I was struck by the contradictory ways Puerto Ricans remembered Pedro Albizu Campos, Nationalist Party president from the 1930s until his death in 1965. I had also been thinking about ghosts and sonic hauntings. After Albizu’s death his voice had a posthumous life in LPs that circulated in the US, Puerto Rico, and Cuba. I have a lot of smaller questions about technology, spies, and 1970s folk singers, but the big questions are: what was the role of speech and recorded sound in the criminalization of dissent in Puerto Rico? What are the contours of diverse “lefts” in the Cold War Caribbean, and what was their relationship to the recording and entertainment industries? How do Puerto Ricans today understand the Nationalists’ failed decolonizing project?

In the course of your research, have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

I was surprised by the blatant unconstitutionality of the “Gag Law” (Law 53) implemented in 1948, which banned expressions of anti-US sentiment. I was also surprised by the extensive surveillance system, involving both people and technology, in place in Puerto Rico in the 1930s and 40s. Finally, I was surprised by the absence of discussions of either of these things in US historiography. It is a forgotten episode that set the stage for the use of technology in future repressive strategies. It also allows for a better understanding of the US as a colonial power.

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

I hope this will encourage and prompt the further consideration of non-textual sources in the production of Caribbean histories. I also hope to unsettle narratives that presume a frictionless path towards liberal hegemonies in Cold War Puerto Rico.

CJ Jones

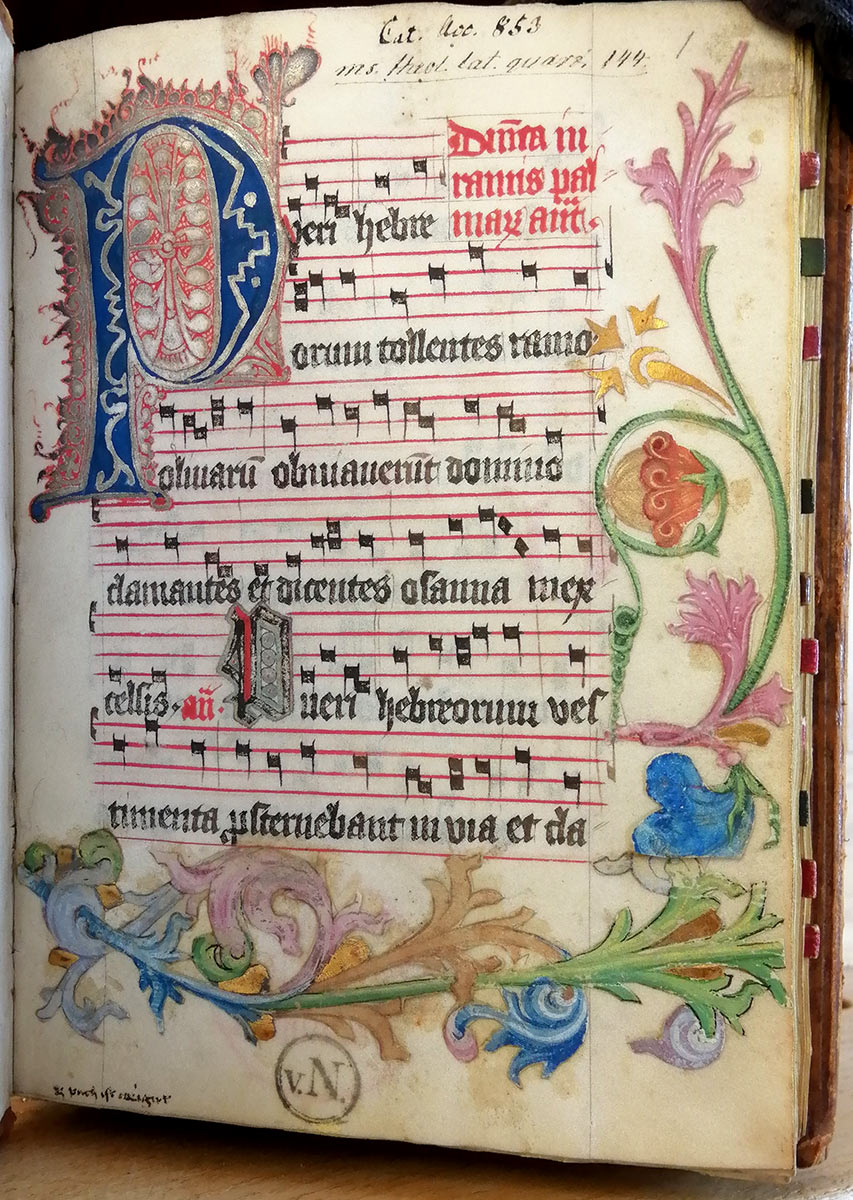

Project Title: Binding Ritual: Enclosed Women, Cultural Authority, and Liturgical Books in Late Medieval Germany

CJ Jones holds an appointment as a professor of German studies at the University of Notre Dame, where they will assume the role of the Robert M. Conway Director of the Medieval Institute after their fellowship at the National Humanities Center. Their interdisciplinary research draws together history, literature, music, liturgy, and manuscript studies to explore how medieval religious women negotiated gendered and religious structures of authority and how liturgical practice afforded flexible opportunities for creating and performing communal identity. Their recent book, Fixing the Liturgy: Friars, Sisters, and the Dominican Rite, 1256–1516 (The University of Pennsylvania Press, 2024), constructs a new history of the Dominican order’s liturgy in the Middle Ages, told from the perspective of women’s communities. Using previously unstudied manuscripts, Jones reconstructs how Dominican sisters orchestrated the sounds, sights, and smells of women’s liturgy on the eve of the Protestant Reformation. Their current research examines small-format manuscripts for worship to uncover how medieval nuns designed and individualized the books guiding their community prayer lives.

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions you are considering?

A couple of years ago a friend of mine put me in touch with a scholar at Northeastern University in Boston (Erika Boeckeler, Associate Professor of English), who was puzzling over the single medieval manuscript owned by her university. It turned out that the manuscript came from the Dominican convent of St. Katherine in Nuremberg, which I had studied a great deal for my first book. It is a miniature prayerbook and I could tell her what some of the prayers were, but it was a bit of a puzzle to me, as well. However, my second book dealt with manuals for liturgical worship that had been composed by medieval women, including the women of this community. Their manuals and diaries explain their practices of prayer and song in detail, so that the lived context of the prayers contained in Northeastern’s tiny book became vibrantly clear. Moreover, it became clear that the women had taken other models and combined them to design a new prayerbook that was optimized for use within their specific community and their specific practices. The “Dragon Prayer Book,” as Professor Boeckeler calls it, became the spark for me to consider the intellectual agency of medieval women in shaping their musical, textual, and material culture by altering their books and designing new book types.

I examine how books directed and governed women’s ritual action, and how women shaped and altered their books to construct a female cultural space through song. Analyzing how religious women tailored their books for liturgical music exposes the webs of opportunity and constraint in which medieval religious women exercised agency in their ritual lives.

In addition to uncovering how medieval nuns exercised cultural independence, creativity, and authority through community rituals and book-making, I explore what these women’s artefacts reveal about the competing principles that all medieval bookmakers had to consider. For example, in deciding how heavily to abbreviate a text, the scribe weighed efficiency in production (abbreviated texts consume less time and materials) against efficiency for the end-user (abbreviated texts may confuse, slow, or hinder the reader). Different bookmakers made different decisions in different contexts, and the design of these women’s books can tell us much about the manifold choices that were (and are!) possible under varying priorities and circumstances.

In the course of your research, have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

One two-volume music manuscript from the women’s community of Gernrode in Central Germany continues to surprise me. Now housed in the Berlin City Library (Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin), it has been known in scholarship for some time, because it contains a quasi-dramatic “Easter play” which has been edited and published, although the rest of the manuscript’s contents have not. I began to look at the manuscripts, because I was interested in the ways in which the Easter play coordinated a joint ritual performed by religious women and male clerics together. The first surprise was that whereas the edition presents the “stage instructions” and music as one holistic script, the manuscripts split these elements up. Most of the manuscripts consists of music without indications for use, and the ritual instructions are located in an appendix at the back of each manuscript. Moreover, the songs used in the Easter play are not organized in the music section in the order in which they are sung in the play. This design seems extremely inefficient for use during performance; were these manuscripts only used in preparation and not during the play itself?

I returned to Berlin in August 2025 to photograph the manuscripts and examine their physical structures so that I can work on them further during the fellowship year at the NHC. In my earlier examination, I had focused on the ritual instructions and had assumed that each manuscript contained the same music, because they contained the same “stage directions.” This is not so! Each manuscript contains a different set of songs, which means that I have not one but two puzzles on my hands. The question expands from “How were these manuscripts used to facilitate performance in a joint male and female community?” to “How did these two manuscripts work together or complement each other in coordinating the ritual lives of these men and women; and why did the person producing these manuscripts choose to create two volumes with different music but identical instructions?”

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

This project will bridge different disciplinary approaches to medieval manuscripts, both in order to enrich research by combining various methodologies and to bring scholars from different fields into conversation with each other. The manuscripts I have chosen for study have often fallen between the cracks in manuscript studies scholarship. Art historians and musicologists tend to examine enormous music books large enough for multiple people to sing from simultaneously. These books contain more information about melodies and are often richly decorated, but their size and weight constrained their possible use in ritual movement. It is difficult to reconstruct women’s dynamic use of space from these immoveable tomes. In contrast, literary historians focus on small books of private prayer, which were often updated and tailored to the tastes of the owners. Private prayer books reveal much about medieval women’s literacy, creativity, and agency in shaping their own expressions of piety, but these guides for individual devotion do not fully reflect the musical and ritual contexts of convent spirituality. My project draws on insights and methods from both areas of research to understand how women shaped and updated their small liturgical books to optimize their individual use during communal ritual, especially during rituals that entailed movement through sacred space.

Young Kyun Oh

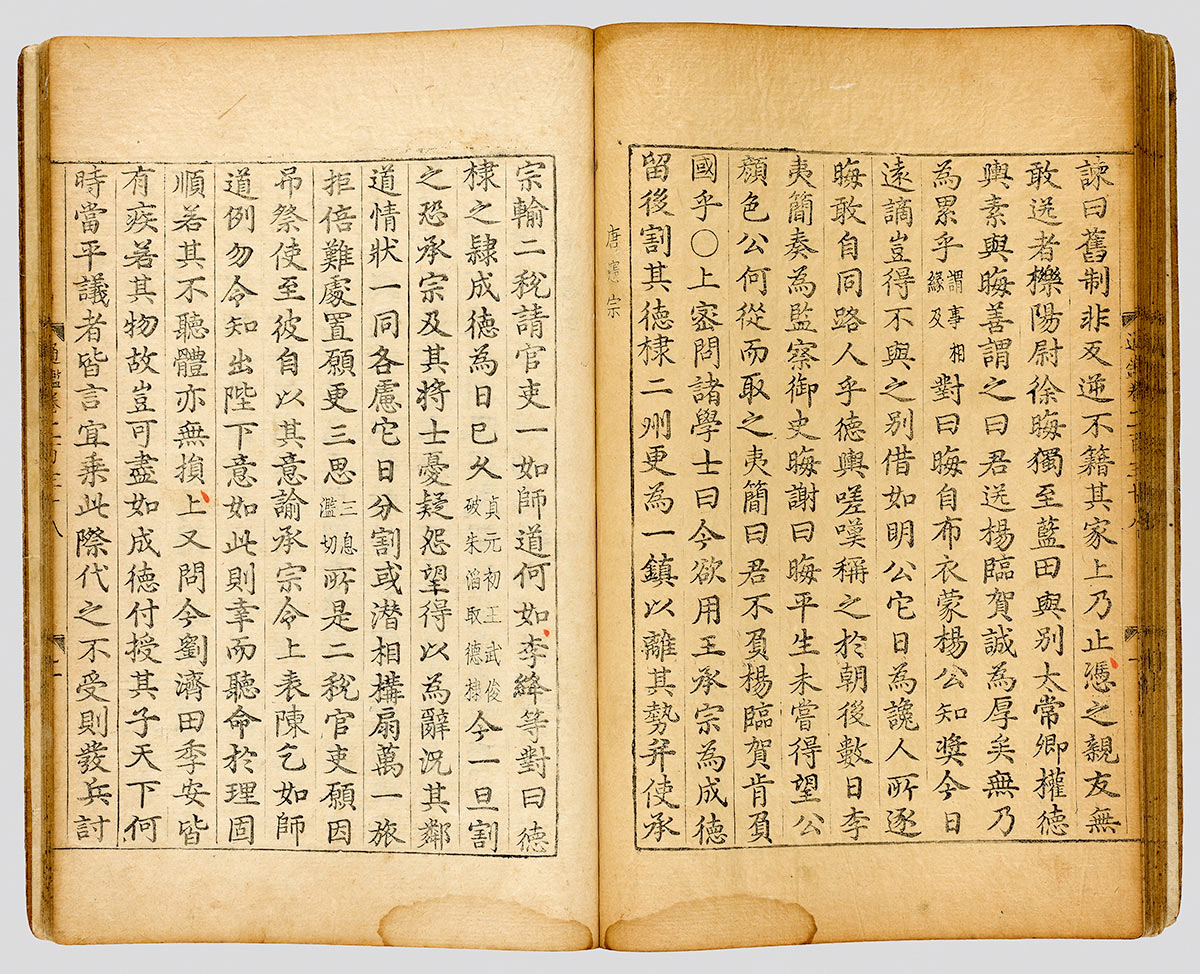

Project Title: The King’s Press: Typography and Printing in Chosǒn Korea (1392–1910)

Young Kyun Oh is an associate professor of Chinese and Sino-Korean at the School of International Letters and Cultures at Arizona State University. His research interests include the connected histories of East Asian languages and of Sinitic books. He was trained in East Asian philosophy, historical phonology of Chinese and Sino-Korean, and Literary Sinitic. He expanded his research to the history of East Asian books, exploring ways to place the premise and adaptation of Korean culture in the Sinophonic and Sinographic sphere. He is the author of Engraving Virtue: The Print History of the Premodern Korean Moral Primer (Brill, 2013), in which he delved into the cultural significance of woodblock printing in Sinitic societies, and articles on the book history, linguistic history, and literature of premodern Korea and East Asia.

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions you are considering?

It is generally accepted that xylography was preferred to metal typography in premodern East Asia. Typography prints text infinitely with a limited number of types. In English, for example, we only need types for fewer than two hundred symbols. But there are tens of thousands of Chinese characters, for which casting type did not make sense economically. Carving woodblocks thus made more sense for Sinitic books. Working on the print history of Korea, I realized that metal typography never ceased throughout the Chosŏn dynasty (1392–1910), almost monopolized by the royal court. In contrast, metal typography was tried briefly in China and Japan only to fall out of use. This brought me to a central question that initiated my current project: Were the Chosŏn kings stupid, holding onto an inferior technology for 600 years? That was the spark.

In the course of your research, have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

While reading ancient Chinese texts in Korean as an undergraduate student, it dawned on me that I was reading a foreign language that was spoken two millennia ago. Learning the history of Chinese and its contact with Korean—two completely different languages—made me wonder how languages transfer from one culture to another. Then I came to realize that Koreans learned classical Chinese solely through books, hardly as a spoken language, including poetry. This led me to studying book history. Investigating woodblock printing in Chosŏn Korea, I was surprised to see a deep-rooted reverence of engraved text, viewing block printing as something more than a technology. Now I am surprised again that typography continued throughout Chosŏn, unlike in China and Japan, despite the dominance of wood-block printing. These were all genuine surprises.

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

An immediate question is about technological ecology. How do two technologies (or more) coexist, serving the same purpose? If one of them is proven to be superior and more suitable to the material and/or social circumstances, does the other just deteriorate and become replaced? I also pay attention to the culture behind technological choices. My previous research interpreted the philosophical dimension behind woodblock printing vis-à-vis the classical idea of literature and ethics in East Asia. This time, I ask the same question about typography. How did (Chosŏn) people interpret and contextualize typography in their social, cultural, and historical habitat? What did Koreans actually do with typography, and how did it affect the course of Korean history and culture? And, by extension, what do we do as humans with books?