This month we highlight the research of 2025–26 Fellows whose projects foreground neglected and other marginalized perspectives within well-trodden historical narratives.

Signe Cohen

University of Missouri

Kathleen DuVal

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Terrion L. Williamson

University of Illinois Chicago

Signe Cohen

Project: “No Other World Than This”: A History of Atheism in South Asia

Signe Cohen is a professor of South Asian religions at the University of Missouri. As a scholar of Hinduism and South Asian Buddhism, her research focuses on classical Indian texts and their linguistic, philosophical, and cultural contexts. She has published widely on topics ranging from ancient Indian automata to the intersections of religion and popular culture. Her current book project, “No Other World Than This”: A History of Atheism in South Asia, offers a comprehensive study of atheistic thought across Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain traditions. Moving beyond the well-known Cārvāka school, the book uncovers broader currents of non-theism and functional atheism in Indian intellectual history. Alongside original textual translations, it traces how South Asian thinkers have articulated systems of ethics, metaphysics, and liberation without reliance on divine beings.

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions that you are considering?

While the religious traditions of South Asia have been extensively studied, the equally deep and enduring strands of atheistic thought have been largely overlooked. Encountering the neglected voices of the Cārvākas, the functional atheism of Buddhists and Jains, and later skeptical currents inspired me to bring these traditions into focus, both to recover their historical importance and to complicate modern assumptions about atheism as a purely Western phenomenon. The big questions driving this project are both historical and conceptual. Historically, how did South Asian thinkers define, debate, and practice forms of irreligion across different periods and traditions? Conceptually, what does it mean to speak of “atheism” outside of Western contexts, and how might the South Asian evidence reshape or expand our definitions of the term?

In the course of your research, have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

What most surprised me was discovering how strongly the sacred persists in traditions that reject gods. In Buddhism, for example, devotion to the three jewels, relics, stupas, and the pursuit of nibbāna all embody realities “set apart” from ordinary life, yet without reference to a personal deity. Rather than erasing the sacred, atheistic traditions often redefine it, locating it in liberation, truth, or emptiness rather than in divine beings. This suggests to me that atheism in South Asia is not simply the absence of belief, but a reimagining of the sacred itself in non-theistic terms.

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

I hope this project will open new avenues for studying atheism as a global, culturally diverse phenomenon rather than a Western-centric category. By foregrounding South Asian voices, it invites scholars to rethink binaries like “religion vs. atheism” and to explore a spectrum of positions that include atheist forms of spirituality. It also creates space for comparative work, placing South Asian traditions alongside other global examples of irreligion, and for interdisciplinary conversations about how humans construct meaning without gods.

Kathleen DuVal

Project: Yorktown: The American Revolution and the Making of the United States

Kathleen DuVal is the Carl W. Ernst Distinguished Professor of History at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Her field of expertise is early American history, particularly interactions among Native Americans, Europeans, and Africans. Her books include Independence Lost: Lives on the Edge of the American Revolution and the Pulitzer Prize-winning Native Nations: A Millennium in North America.

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions that you are considering?

I wanted to bring a multi-perspectival historical narrative to the heart of the American Revolution.

In the course of your research, have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

I was surprised to learn that there were Native American reservations in Virginia at the time of the American Revolution—telling the stories of their interactions with the Revolution was part of the impetus for the project.

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

I hope historians keep returning to the stories we think we know well, in order to tell them from new angles.

Terrion L. Williamson

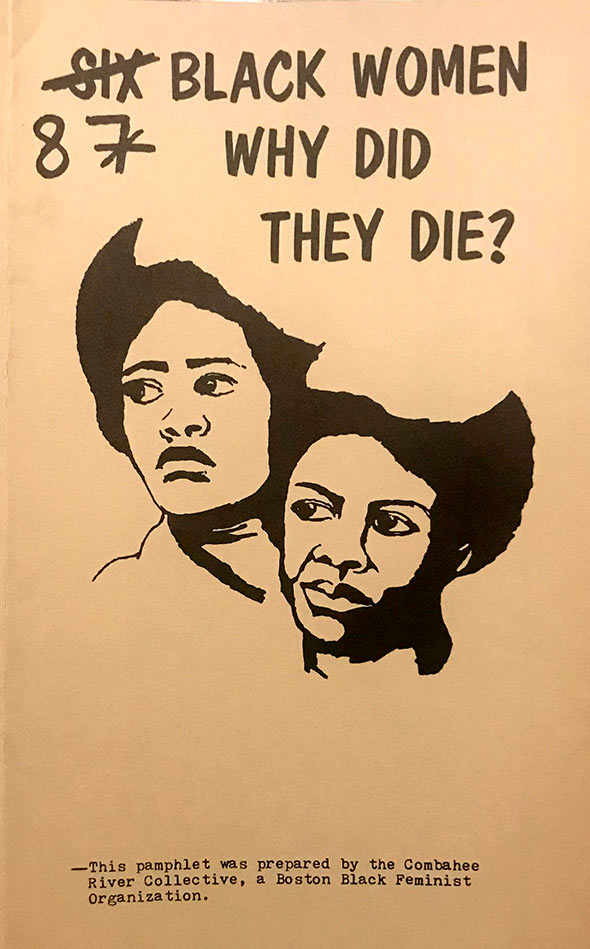

Project: The Unreckoned: Black Women, Serial Murder, and the Decline of the All-American City

Terrion L. Williamson is an associate professor of Black studies and Gender and Women’s studies at the University of Illinois Chicago, where she also serves as the founding director of the Black Midwest Initiative. She is the author of Scandalize My Name: Black Feminist Practice and the Making of Black Social Life and the editor of Black in the Middle: An Anthology of the Black Midwest. She is also coeditor, with Delia Fernández-Jones, of the University of Nebraska book series Reimagining Race and Region in the American Midwest. Born and raised in Peoria, Illinois, she conducts research on working-class Black life in the deindustrializing Midwest, with a particular emphasis on Black women’s experiences of interpersonal harm and gender violence. Currently, she is working on a book that centers the story of nine Black women who were killed in her hometown between 2003 and 2004.

What was the initial spark that led you to this project? What are the big questions that you are considering?

Between 2003 and 2004, nine Black women were killed over the course of 15 months in Peoria, a small city located about halfway between Chicago and St. Louis in central Illinois. Peoria is my hometown. Most of the women were killed in a house that is located less than a mile from the family home where I spent most of my childhood and where my parents continue to live to this day. I also knew one of the victims personally. I began this work because I wanted to understand what had happened to those women—not simply who had killed them, but what had happened to them. What were the conditions of possibility for those nine Black women to be killed when, where, and how they were? And what are the implications of their deaths, and the deaths of so many Black women like them, for Black struggle more generally?

In the course of your research, have you run across anything that genuinely surprised you? What can you tell us about it?

When I began researching the Peoria case more than twenty years ago, I had no idea that hundreds of Black women and girls have been the victims of serial murder across the United States since the early 1970s. The image of the serial killer—and, by extension, the serial killer’s victims—I had in my mind back then had largely been shaped by the slasher films I had grown up consuming in the 1980s and 1990s and by sensationalized news media that never featured victims who looked like me or the women and girls from my community.

What new avenues of inquiry do you hope this research will prompt or make possible in your field?

When Black women started turning up dead in Boston in 1979, the Combahee River Collective refused the idea that the deaths of those women somehow were not connected because they were not all killed by the same person. Rather than focus on the identity of the killer or killers, Combahee centered the women who had been killed, contending that ending such violence required attending to the larger socioeconomic conditions of Black women’s marginalization and oppression and not simply locking up whoever was responsible for doing the killing. My work follows in this worthy tradition, adding to the popular preoccupation with true-crime media an analysis that is both deeply researched and deeply rooted in a personal story of home.