This is a précis of an argument that I developed in an article called “Did Darwin Write the Origin Backwards?” The article was published in 2009 and may be found on my web set at http://philosophy.wisc.edu/sober/recent.html. An expanded version of the argument is the first chapter of a book that I’m publishing at the end of 2010 with Prometheus Books. The book has the same title as the 2009 article.

Although Darwin’s theory is often described as the theory of evolution by natural selection, most commentators recognize that common ancestry (the idea that all organisms now alive on earth and all present day fossils trace back to one or a few “original progenitors”) is an important part of the Darwinian picture. What has been less explored in Darwin studies is how these two parts of Darwin’s theory – common ancestry and natural selection — are related to each other. Ernst Mayr and others have noted that they are logically independent. But this leaves open how the two ideas are evidentially related. How does common ancestry affect the way in which evidence concerning natural selection should be evaluated? And how does natural selection affect the way in which evidence concerning common ancestry should be evaluated?

Darwin addresses one of these two questions very succinctly in a passage from the Origin:

… adaptive characters, although of the utmost importance to the welfare of the being, are almost valueless to the systematist. For animals belonging to two most distinct lines of descent, may readily become adapted to similar conditions, and thus assume a close external resemblance; but such resemblances will not reveal – will rather tend to conceal their blood-relationship to their proper lines of descent.

The fact that human beings and monkeys have tailbones is evidence for common ancestry precisely because tailbones are useless in humans. Contrast this with the torpedo shape that sharks and dolphins share; this similarity is useful in both groups. One might expect natural selection to cause the torpedo shape to evolve in large aquatic predators whether or not they have a common ancestor. This is why the adaptive similarity is almost valueless to the systematist who is trying to reconstruct patterns of common ancestry.

In this passage, Darwin is saying that to determine whether a trait shared by two species is strong evidence that they have a common ancestor, one must be able to judge whether there was selection for the trait in the lineages leading to each. In this sense, knowledge of natural selection is a prerequisite for interpreting evidence concerning common ancestry. However, there is a subtly different question that has a very different answer. Must natural selection have been an important influence on trait evolution for there to be strong evidence for common ancestry? Darwin’s answer to this question is no. A world in which organisms are saturated with neutral and deleterious similarities, while adaptive similarities are rare or non-existent, would be an epistemological paradise so far as the hypothesis of common ancestry is concerned. That’s the point that Darwin is making in the passage I just quoted. Inferring common ancestry does not require that natural selection has occurred.

What about the converse question – how does the fact of common ancestry affect the interpretation of evidence for natural selection? One of Darwin’s most famous arguments concerning natural selection does not depend one whit on common ancestry. This is Darwin’s Malthusian argument. If reproduction in a population outstrips the supply of food, the population will be cut back by starvation. If the organisms in the population vary with respect to characteristics that affect their ability to survive, and if offspring inherit these fitness-affecting traits from their parents, the population will evolve. The process of natural selection is a consequence of these conditions and it can and will occur even if no two species have a common ancestor.

All this is correct, but there is more to the Darwinian picture of natural selection than this. The Malthusian argument establishes that selection has occurred – that some traits changed frequency because of their influence on the viability of organisms. But which traits evolved by natural selection? Darwin doesn’t think that every trait we observe evolved because there was selection for it; recall his comment in the Origin that selection is “the main but not the exclusive cause” of evolution. And if a trait did evolve under the influence of natural selection, why was it favored by natural selection? It is these questions, which concern the detailed application of the hypothesis of natural selection to examples, that common ancestry helps to answer.

An interesting illustration of how Darwin uses the assumption of common ancestry to think about natural selection may be found in his discussion of why mammals in utero have skull sutures that allow them to pass through the birth canal:

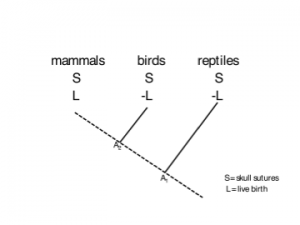

The sutures in the skulls of young mammals have been advanced as a beautiful adaptation for aiding parturition [live birth], and no doubt they facilitate, or may be indispensable for this act; but as sutures occur in the skulls of young birds and reptiles, which have only to escape from a broken egg, we may infer that this structure has arisen from the laws of growth, and has been taken advantage of in the parturition of the higher animals.

On the face of it, Darwin’s reasoning here is odd. If he wants to evaluate the hypothesis that mammals have skull sutures because this facilitates live birth, why does he consider the fact that nonmammals have the sutures but not the live birth? Let us hope that he isn’t thinking that if a trait T evolved because the trait facilitated X in one lineage, that T cannot be present without X in any organisms on earth. Penguins do not refute the hypothesis that wings evolved to facilitate flight in birds. And the hypothesis that a species of lizard evolved its green coloration because this color provided camouflage does not require that every green organism on earth gains protective coloration from its being green.

What Darwin is doing in this and in other similar passages is exploiting the fact of common ancestry to test hypotheses about natural selection. The reason that birds and reptiles are relevant to the question of why mammals have skull sutures is that all these organisms share a common ancestor. Common ancestry allows Darwin to infer what happened in the lineage leading to modern mammals. The fact that present day birds and reptiles have sutures but no live birth is evidence that sutures were present in the lineage leading to modern mammals before live birth evolved. If so, the sutures did not evolve because they facilitated live birth. On the contrary, live birth evolved after the sutures were already in place.

Darwin does not spell out the details of this inference, but modern evolutionary biologists will recognize it as an application of the principle of parsimony. Consider the phylogenetic tree shown in the accompanying figure. The tips of the tree represent modern mammals, reptiles, and birds. This is not the tree that a modern biologist would draw, but it may well have been the one that Darwin thought is true. As you move down the page, you are moving from present to past. The lines represent lineages; when two of them coalesce, you have reached a common ancestor. The tree says that mammals and birds are more closely related to each other than either is to reptiles; A2 is an ancestor of the first two, but not of the third. If you go sufficiently far into the past, you will find a common ancestor (A1) that unites all three of these present day groups.

The figure also indicates the traits (±skull sutures; ± live birth) that contemporary mammals, birds and reptiles exhibit. Given this tree, and the features exhibited by its tips,

what is the most reasonable inference concerning the characteristics of the ancestors A1 and A2? The most parsimonious inference is that A1 and A2 both have skull sutures but no live birth. This is the most parsimonious reconstruction in the sense that it requires fewer changes in character states in the lineages leading to the present than any other reconstruction. If this most parsimonious reconstruction is correct, we can deduce that skull sutures evolved before live birth made its appearance in the lineage leading to modern mammals; the mammalian lineage is represented in the figure by a broken line. This parsimony argument justifies Darwin’s statement that sutures now facilitate, or may even be indispensible for, live birth in mammals, but this is not why the sutures evolved.

The argument just described raises an interesting philosophical question: why should we think that the principle of parsimony is a good inferential rule? Why should we think that the most parsimonious hypothesis is true? I won’t pursue this enticing question here. Rather, the point of relevance is that in Darwin’s theory, and in the evolutionary biology of the present, common ancestry is not an unrelated add-on that supplements the hypothesis of natural selection. Instead, common ancestry provides a framework within which hypotheses about natural selection can be tested. In Darwinian biology, a lineage is like a mineshaft that extends from the surface of the earth to deep below, with multiple portholes connecting surface to shaft at varying depths. By peering into a porthole, we gain evidence about what is happening in the shaft. The more portholes there are, the more evidence we can obtain. Thanks to common ancestry, facts about the history of natural selection become knowable.

There is an asymmetry in how common ancestry and natural selection are related to each other in Darwin’s theory. To get evidence for common ancestry, natural selection need not have caused any of the traits we now observe. But to get evidence for natural selection, Darwin needs to be able to think of present day organisms as tracing back to common ancestors. Selection doesn’t make adaptations out of nothing; adaptations are modifications of the traits of ancestors. To know what those ancestors were like, we need to be able to infer their characteristics from what we now observe. It is common ancestry that makes those inferences possible.

If this is the right picture of how common ancestry and natural selection are related in Darwin’s theory, a puzzle presents itself: why did Darwin write the Origin by front-loading natural selection? Darwin does mention some ideas about common ancestry early in the book, but the big picture of there being one tree of life for the whole living world emerges only gradually, and later. On the whole, it is natural selection that comes first. Why is the book structured like this? Why didn’t Darwin begin by defending the idea of common ancestry and then gradually introduce natural selection as a secondary theme?

Elliott is right: from an evidential point of view it appears as though Darwin wrote the Origin backwards. It seems that Darwin should have first made the case that evolution has in fact occurred and that the history of life has a tree structure. Then natural selection could take the stage to explain some of the patterns in the history of life. This not only makes sense evidentially, but also rhetorically, since it introduces the explanandum before the explanans: Natural selection is a mechanism that explains patterns of evolutionary change, but before we know that there are such patterns, we have little incentive to accept a mechanism that is supposed to explain them.

However, I think that there are very good reasons why Darwin begins with selection and only then argues for the tree of life. The most convincing kind of argument is often one that begins with an observation that is indisputable, and then leads, through small and innocuous steps, to the desired conclusion. It is precisely this strategy that Darwin employs in the Origin. This approach was particularly important in the historical context in which Darwin developed his ideas. The tree of life was a hard pill to swallow for Darwin’s contemporaries: the geological record was spotty and the patterns of traits across extant organisms would not readily convince many that all life evolved from one or a few progenitors. Darwin knew that his many of his readers would be unable to accept the notion of the tree of life unless it were preceded by the concept of natural selection.

To ready his contemporaries for accepting the tree of life, Darwin needed to establish three key premises: (1) evolution by natural selection occurs and can create varieties, (2) these varieties form lineages, and (3) there is no fundamental difference between varieties and species. To establish (1), he begins with artificial selection and the fact that humans have precipitated change in domesticated animals through generations of selective breeding. This is the evolution via selection that all of his contemporaries would be familiar with, even if they had not conceived of it as such. Artificial selection is often accomplished with a conscious goal of change in mind, as in the case of the pigeon fancier, who might desire a long beak in one of its varieties, and therefore allow only the longest beaked individuals of that variety to breed. Darwin thus led his readers to contemplate a pigeon tree of life, formed via evolution by artificial selection. But to establish (1), he has to replace artificial selection with natural selection. He does this with an ingenious use of an intermediate step, “unconscious selection.”

Although the pigeons were selected consciously, Darwin points out that evolution by artificial selection can occur unconsciously as well. A farmer might merely want his sheep to be maintained as good stock, and selects for breeding what are deemed good, healthy individuals. No new traits are the desired outcome, but nonetheless sheep on different farms will diverge because of this selection process. It is then a small step for Darwin to lead the reader to the idea that natural selection is just like unconscious selection, except that the environment is the sole selector, not, as in the case of the sheep, the environment plus the farmer. The formation of varieties by natural selection, (1), is then established. And it is not too much of a leap to see that just as sheep and pigeons form lineages with progenitors, so can wild animals.

Given (1) and (2), Darwin would have been able to make the case that varieties could be formed in the wild via natural selection. But he had not yet shown how species could evolve. He knew that many of his contemporaries would be able to accept the formation of varieties, but would balk at the idea of naturally produced species. Interestingly, Darwin made the case for naturally produced species by arguing that a species is not an objectively real biological category—he aimed to show that a given taxonomy is as much a result of the inclinations of the taxonomists as it is natural divisions in the world. Genera are not different in kind from species and species are not different in kind from varieties (3). He did so by citing the divergent taxonomies: “few well-marked and well-known varieties can be named which have not been ranked as species by at least some competent judges” (1859, pg. 47).

With (1) – (3) established, Darwin makes it at least conceivable that lineages of species can form via the process of natural selection. It is then that the stage is set for his argument for the tree of life.

Today, with radiometric dating techniques and fossils like Tiktaalik, solid arguments for the tree of life can be made in the absence of natural selection. Had Darwin access to these data, perhaps he would have followed Elliott’s suggestion of presenting the case for the tree of life first. But without such an evidential foundation, Darwin had to ready his readers for what would otherwise seem too great a leap of faith.

Like Grant Ramsey, I am less perplexed by the structure of Darwin’s Origin than Elliot Sober is. Indeed, I suspect that Sober’s puzzles about the order in which natural selection and common ancestry are discussed are in part an artifact of an equivocation on “natural selection.” I will, anyway, try to explain how I see matters, and to do this I need to make a pair of distinctions: the terms “theory of evolution” and “natural selection” both require disambiguation.

First, we need to expose a common equivocation (one not made in Sober’s essay) on “evolutionary theory.” In the Origin, Darwin really put forward two things that are commonly referred to as the theory of evolution. On the one hand, Darwin presents the theory of evolution as a theory that explains the origin of species. This theory is a theory of a single thing, a complex historical event in which one or a few original life-forms diversified and branched out to produce the manifold different species that have arisen in the Earth’s history. This theory is like the theory of continental drift, which equally posits a complex, temporally attenuated process with lots of moving parts that eventuates in a particular distribution of masses on the surface of the planet. The Big Bang theory of the origin of the universe is another similar sort of theory. Call this theory of evolution TOE1. TOE1 is not Darwin’s idea; several other thinkers (Lamarck, Chalmers, Darwin’s grandfather) had undertaken it, though none had defended it nearly as well as Darwin does in the Origin.

The other thing commonly called “evolutionary theory” that Darwin puts forward in the Origin, something that is Darwin’s idea (though Wallace thought it up, too), is a theory of the dynamics of a subset of natural systems. This is what is presented in the first few chapters of the Origin. Systems that meet certain specifications, their members exhibit heritable variations and struggle for existence, are governed by this theory, call it TOE2. TOE2 allows us to draw conclusions about the dynamics of the systems it governs, typically that individuals in the system with heritable variations more conducive to survival and reproduction will spread at the expense of those with less adaptive variations. Unlike TOE1, which is about a single complex process, TOE2 is a general theory, one that applies to any system with the right features. Indeed, as advocates of Universal Darwinism have claimed, TOE2 could even be applied to unearthly systems; it is nowadays used to explain the dynamics of systems of cultural variations and scraps of computer code. TOE2 is similar to other theories in the special sciences, such as econometrics, ecology, and phenomenal physics; it is what has grown into our modern day population genetics. Importantly, the individuals in a system governed by TOE2 need not be related by common ancestry.

TOE1 and TOE2 do, of course, interact in Darwin’s Origin. Darwin’s main aim in that work is to convince the reader that TOE1 is a better explanation for the origin of species, and their adaptations, than is special creation. The latter part of the Origin marshals evidence from embryology, geology, and the distribution of plants and animals around the globe in service of this goal. But before TOE1 can be sent into battle against the theory of special creation, Darwin first needs to convince the reader that TOE1 is a candidate explanation for adaptations and the origin of species, something that could explain these things. Darwin needs to get TOE1 on the table, and to do this, he needs a mechanism by which the adaptation and diversification of life on Earth could have occurred. TOE2 provides an account of this sort of process. Crucially, previous defenders of TOE1 lacked a good explanation of how evolutionary change could occur. So, the answer to Sober’s question, Why did Darwin write the Origin by front-loading natural selection, is that Darwin did so because he had to provide an account of how episodes of evolution leading to diversification and adaptation could occur in nature before arguing for his stance that the evidence favors his view, that life on earth repeatedly underwent such episodes of evolution, over the creationist alternative.

Darwin front-loads “natural selection” in the Origin in the sense that Darwin presents TOE2 and defends it as a theory that can explain how natural populations evolve before he considers at any depth the evidence for TOE1. But there is another sense of “natural selection” at work in Sober’s essay; the transition between the two occurs when Sober writes “there is more to the Darwinian picture of natural selection than [the Malthusian argument].” Biologists are sometimes concerned with the question of whether this or that trait in this or that lineage evolved as the result of a process governed by TOE2, if you like, as the result of a process of natural selection. As Sober discusses, the features of ancestors and other relatives sometimes serve as evidence for such claims. But, as Sober notes in his discussion of Darwin’s “Malthusian argument,” “natural selection” as a general theory, what I have been calling TOE2, does not depend on common ancestry, even though facts about common ancestry are relevant to the evidence for specific claims that specific traits in specific lineages evolved by a process governed by TOE2.

In general, the evidence relevant to the question, was process A governed by theory B, is different from what makes us accept theory B as a general theory. When Sober writes that “in Darwin’s theory, and in the evolutionary biology of the present, common ancestry is not an unrelated add-on that supplements the hypothesis of natural selection,” this is true only if one means by “Darwin’s theory” TOE1, and only if one means by “natural selection” that this or that specific trait in this or that specific lineage evolved by means of a process governed by TOE2. But common ancestry is an unrelated add-on to Darwin’s theory of natural selection if one means by that phrase TOE2, so TOE2 can be presented before a discussion of common ancestry, as it is in Darwin’s celebrated work.

Elliott’s central point is that the theory that diverse living species show descent from common ancestry is not supported by evidence showing that natural selection is responsible for evolutionary change. In contrast, the theory of evolution by natural selection is supported by evidence of common ancestry. I would like to explore this asymmetry by clarifying what one means by the “theory of evolution by natural selection.”

As Elliott points out, the idea that natural selection happens, while novel in Darwin’s time, is also rather obvious. One can logically deduce that natural selection must happen given just three postulates, all elegantly explored in the Origin: heritable phenotypic variation is found in populations, some of that phenotypic variation influences the probability that organisms leave descendants, and there are finite resources. If the “theory of natural selection” is merely that selection “works,” there is no need to invoke the theory of common ancestry. After all, if there were just one population-lineage on the planet, common ancestry would not hold, yet natural selection would still be an ongoing process.

The version of the theory of natural selection that Elliott has in mind is a more ambitious one: the differences among living species, and specifically those differences that correlate with species’ ways of life, are the result of natural selection acting over long periods of time. Does this claim depend upon the principle of common ancestry? Suppose that each living species had originated independently. It would be possible that, after their origination, each species had evolved via natural selection to become better suited to their way of life? Thus, at first glance, the more ambitious theory of natural selection also seems independent of the truth of the theory of common ancestry. Somebody could theoretically hold that complex adaptations are due to natural selection even if they believed in separate origins for each living species. Common ancestry and evolution by natural selection are logically independent of one another.

Despite this independence, Elliott, is correct that the more ambitious theory of natural selection is aided by evidence that common ancestry is true and separate ancestry is false. Under separate ancestry, natural selection doesn’t do any explanatory work. Given that neither the separate nor the common ancestry models offer a theory for how life originates, there is nothing to say that life couldn’t originate perfectly adapted. Under a separate ancestry model, one theory, origination in a state of adaptive perfection, is more parsimonious (or at least no less parsimonious) than the theory that there were multiple originations in a maladaptive state, followed by selection towards greater adaptation. Under separate ancestry, evolution is superfluous. In contrast, even if the first life form was perfectly adapted, common ancestry would still requires us to explain how one ancestral form can give rise to diversely adapted, living forms. Given common ancestry some theory of adaptive evolution is needed. The question is just whether natural selection is the best theory of evolution.

Thus, I do agree with Elliott that common ancestry is supportive of the (ambitious) theory of evolution by natural selection. However, an extension of the same argument can be used to show that common ancestry also depends upon natural selection. If natural selection is the only viable theory of evolutionary change, yet selection cannot explain how one common ancestor could gave rise to descendants as different as spiders and flamingos (to give an example raised by a student this week in class), then, however compelling the evidence might support of common ancestry, we should nonetheless have to favor multiple separate origins of life. Darwin saw this clearly. He knew that evidence for common ancestry, of which he saw lots, would be undermined by an absence of a sufficient theory of adaptive evolution, as summarized in the introduction to Origin of Species:

This quote shows that Darwin sensed that the abundant evidence suggesting common ancestry would only sway his fellow naturalists if he could open their minds to the possibility of a natural mechanism explaining adaptation. Maybe this is why Darwin wrote the origin “backwards.”

I agree with Elliott Sober that common ancestry can be tested independently of any knowledge of natural selection. In fact, I think the best evidence for common ancestry has nothing to do with natural selection and I think Darwin did too (see Chapter 13 of The Origin where he talks about classification). But this doesn’t mean that the theory of natural selection is evidentially irrelevant for common ancestry. Natural selection provides a mechanism of change which is required if there is to be any divergence from the common ancestor. It is easier to find common ancestry more plausible in the case of the pigeons in Chapter 1 than in the case of plants and animals precisely because we find it easier to imagine how populations could undergo a small amount of change as opposed to a large amount of change. This is no mere psychological bias; it represents good scientific reasoning. Sober doesn’t say otherwise in his essay, but he focuses on whether natural selection is necessary for evidence of common ancestry and ignores the question of whether it can provide evidence. Providing a mechanism that can supposedly lead to arbitrarily large amounts of change as Darwin thought natural selection could (though I would debate that this is the case), makes it far more plausible that very distinct morphological groups share a common ancestry. In effect, the theory of natural selection lowers the bar for how much evidence is needed for specific arguments for common ancestry.

Another key factor that I think is missing from this discussion is that Darwin thought of his theory differently than Sober does who treats it how we generally think of evolutionary theory today. It is not an accident that the tree diagram in The Origin which is used to help explain common ancestry actually appears in the chapter introducing natural selection (Chapter 4). In the figure, the x-axis represents morphological differentiation and Darwin hypothesized that natural selection will create divergence through time through selection against intermediate states. Related arguments are given that natural selection is intimately tied to the creation of new varieties or forms and then ultimately to the creation of new species. The branching tree is a description of both process and product and therefore natural selection and common ancestry are part of a single story of the natural history of life for Darwin and not really separable hypotheses about how that story goes.

As for the real reason that Darwin put natural selection first in The Origin, I could only speculate about a number of possible reasons, none of which I would have any evidence for. But were he merely concerned with presenting a logical, structured argument worrying only about testing various parts of his theory and making sure to first argue for any premises needed for any arguments before using them, it still might be the case that he would discuss natural selection before discussing common ancestry. While it would be essential to discuss common ancestry before testing any claims about particular traits such as that mammalian skull sutures were selected for in order to ease live birth, in arguing for common ancestry, Darwin utilizes the fact that species change through time and that they multiply first by developing new varieties and then – via the principle of divergence – they develop into new species. These ideas follow from Darwin’s earlier discussions of the general theory of natural selection which do not obviously depend on prior arguments for common ancestry.

The title of Darwin’s book is On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life. The title was well chosen. The hypothesis of evolutionary connections among organisms was widely discussed at the time, but the origin of the pervasive and obvious adaptations of organisms had no better explanation than divine providence. If this explanation were correct, then divine intervention must have been extremely common. And if it were so common, special creation of each species, or perhaps in some cases ancestors of small groups of species, would be only a small additional step.

Evolutionary divergence of species has two components, reproductive isolation and changes in phenotype and ecology. Virtually all current work on speciation is restricted to the first component. As a result, there is now a common view that Darwin didn’t actually explain the origin of species. This view is incorrect. What he showed is that geographic races can diverge to an indefinite extent, thereby forming what were then regarded as species. Such divergence to an indefinite extent is precisely what Wallace also explained, thereby catalyzing the writing of the Origin.

Darwin had started his notebooks specifically to deal with “the species question”. He worked on barnacles in order to gain detailed familiarity with species in a real group. The diverging characters of species commonly reflect adaptation, and explaining such adaptation was the crux of the species question.

Both Wallace and Darwin discovered natural selection by filling in a deductive argument (Van Valen, 1976). Wallace actually realized this later. This deductive argument is the only place where a Malthusian perspective enters, and both authors said that their reading Malthus led to the discovery.

Adaptation, and thereby species divergence, was the glaring hole in understanding before Wallace and Darwin. Darwin filled this hole in the first part of the Origin. He didn’t write it backwards.

Van Valen, L. 1976. Domains, deduction, the predictive method, and Darwin. Evolutionary Theory 1: 231-245.

The logical independence between common ancestry and natural selection in evolutionary theory is very interesting. The tree of life allows (and tells virtually nothing about) a number of candidate mechanisms and also – I would add – rates of change. I see such logical independence as often reflected in some “divisions of labour” in biological sciences, and in philosophy of biology as well – usually to the detriment, it seems to me, of phylogenetic issues.

Bridging common ancestry and mechanisms of change appears as a fertile ground of reflection, and I think Elliot’s idea of “evidentially relatedness” is very helpful. And, if common ancestry and natural selection need each other to shape their own evidence, who came first?

I want to argue that common ancestry came first. Natural selection was not needed for it, because another, much more ancient notion was on the table: adaptation, or adaptedness if we like.

Adaptation was deeply engrained in a philosophical worldview that saw species as perfectly designed, harmoniously adapted to each other and to their environment. As we all know, such was the view by William Paley and natural theology. Darwin had Paley’s book in his cabin on the Beagle, and Captain Fitzroy wrote in his journal, about Galàpagos finches:

All the small birds that live on these lava-covered islands have short beaks, very thick at the base, like that of a bullfinch. This appears to be one of those admirable provisions of Infinite Wisdom by which each created thing is adapted to the place for which it was intended (see this great website).

At times, appeals to the pervasive adaptive design worldview appear in the Origin, as well. Consider the following excerpt:

We see these beautiful co-adaptations most plainly in the woodpecker and missletoe; and only a little less plainly in the humblest parasite which clings to the hairs of a quadruped or feathers of a bird; in the structure of the beetle which dives through the water; in the plumed seed which is wafted by the gentlest breeze; in short, we see beautiful adaptations everywhere and in every part of the organic world (I edition, pp. 60-61).

In sum, adaptation (as a state, not a process) was something everyone could see.

In reading Darwin’s writings – not just the Origin, but also his Notebooks and The Voyage of the Beagle – I got the idea that the tree of life (or, the coral of life, but this is another story) resulted eventually as an answer to at least five puzzles Darwin had, and obstinately pursued. I wrote “eventually” although, of course, due to how mind works, it is likely that some idea of common ancestry had driven Darwin’s observations and reflections since well before his “I think” picture (Notebook B, p. 37, 1837).

The five puzzles can be seen, I think, as resulting from conflict between a growing mass of empirical observations and the assumptions of a worldview that saw species as perfectly adapted and specially created for their role and place. Such puzzles to me were:

1. Uncertainty of species boundaries due to large individual variation. To follow up from the finches example, I would point out that Darwin wrote in the Origin: «Many years ago, when comparing, and seeing others compare, the birds from the separate islands of the Galapagos Archipelago, both one with another, and with those from the American mainland, I was much struck how entirely vague and arbitrary is the distinction between species and varieties» (I ed., p. 48). Darwin was similarly puzzled by botanists, on whom he wrote: «Compare the several floras of Great Britain, of France or of the United States, drawn up by different botanists, and see what a surprising number of forms have been ranked by one botanist as good species, and by another as mere varieties» (Ibidem). How were the ubiquity of intermediates and the arbitrariness of boundaries consistent with the view of discrete, separately created species?

2. Biogeographical relationships. Darwin noticed very special similarity relations between species that are geographically contiguous. He narrated in The Voyage that, in Galàpagos, «It was most striking to be surrounded by new birds, new reptiles, new shells, new insects, new plants, and yet by innumerable trifling details of structure, and even by the tones of voice and plumage of the birds, to have the temperate plains of Patagonia, or the hot dry deserts of Northern Chile, vividly brought before my eyes» (II ed., p. 393). Why species that are created for similar environments but live far away differ more deeply than those that live nearby and are differently adapted?

3. Relationships between extant and fossil species. Here is another, purposely cryptic excerpt from Darwin’s Voyage: «The relationship, though distant, between the Macrauchenia and the Guanaco, between the Toxodon and the Capybara,—the closer relationship between the many extinct Edentata and the living sloths, ant-eaters, and armadillos […] are most interesting facts […]. This wonderful relationship in the same continent between the dead and the living, will, I do not doubt, hereafter throw more light on the appearance of organic beings on our earth, and their disappearance from it, than any other class of facts» (II ed., p. 173). Darwin was noticing that replacement in time conserves deep similarity as much as replacement in space does, and wondered how continuity in swarming variation could be consistent with special, individual acts of creation.

4. Imperfect adaptation. Darwin will extensively address this issue in his work on orchids (1877). In the Origin I would just point out a related, puzzling phenomenon: «From the extraordinary manner in which European productions have recently spread over New Zealand, and have seized on places which must have been previously occupied, we may believe, if all the animals and plants of Great Britain were set free in New Zealand, that in the course of time a multitude of British forms would become thoroughly naturalized there, and would exterminate many of the natives» (p. 337). If adaptation to local environment is perfect, how can few alien species (as we call them today) compete and supplant native ones?

5. Rudimentary organs. Darwin found the current explanation of them deeply unsatisfactory: «In works on natural history rudimentary organs are generally said to have been created “for the sake of symmetry,” or in order “to complete the scheme of nature;” but this seems to me no explanation, merely a restatement of the fact […]. In reflecting on them, every one must be struck with astonishment: for the same reasoning power which tells us plainly that most parts and organs are exquisitely adapted for certain purposes, tells us with equal plainness that these rudimentary or atrophied organs, are imperfect and useless» (Origin I ed., p. 453). Yes: «Nothing can be plainer than that wings are formed for flight, yet in how many insects do we see wings so reduced in size as to be utterly incapable of flight, and not rarely lying under wing-cases, firmly soldered together!» (Ivi, p. 451). Why this?

The tree of life was an answer capable to frame all these puzzles, furthermore turning them into evidence for its own reality: intermediates were seen as transition forms, taxonomical difficulties as marks of the arbitrariness of operating cuts in a continuous process, biogeographical and temporal succession relationships as proxies for relatedness, imperfect adaptation and rudimentary organs as withstanding traces of the past.

Today we tightly link adaptation to natural selection, and undoubtedly the latter is explanatorily related to common ancestry. But the idea of adaptation has been around for thousands years, and I would say that common ancestry was established against that ancient adaptationist background. I really like Elliot’s enlightening statement:

A world in which organisms are saturated with neutral and deleterious similarities, while adaptive similarities are rare or non-existent, would be an epistemological paradise so far as the hypothesis of common ancestry is concerned.

The described paradise, however, has been far from existence in humans’ reflections on the organic world even in absence of natural selection. Another kind of paradise, one in which organisms are perfectly adapted, was the stage whose cracks triggered the discovery of common ancestry.

P.S. As for the rhetorical strategy of the Origin, I guess it could be explained by a mixture of, at least, (1) Darwin’s rewriting (and reshaping) of his research after the accumulation of evidence from multiple sources (e.g. animal and plant breeders) that he was able to do since his return in England, all concerning his mechanism for change, i.e. natural selection; (2) Darwin’s attraction for mechanistic explanation, which we could see as a function of Zeitgeist, and variously define as Victorian, positivist, or informed by classical mechanics; (3) the rhetorical force that Darwin could entrust, for the same reasons exposed in (2), to the mechanism of natural selection towards his audience.

In thinking about the evidential asymmetry that Elliott describes so fascinatingly, it’s helpful, I think, to recall Darwin’s fidelity to the vera causa, or “true cause”, tradition of scientific argument. I’ll briefly summarize that tradition, then suggest one way in which it seems to bear on Elliott’s analysis.

To be a vera causa thinker was to prize scientific reasoning based on causes whose existence was not merely hypothetical. Before exploiting a putative cause’s power to explain phenomena of interest, one had to show, on independent grounds, that there was impressive evidence both for the existence of the cause and for its being adequate or competent to bring about phenomena of the right magnitude. The best evidence of all was observational: the cause’s operation had been witnessed. The next best thing was inference by analogy from what had been observed.

With this tradition in view, we can, I think, be a little more discriminating about the role of evidence in Darwin’s arguments for natural selection and common ancestry in the Origin. Elliott writes: “There is an asymmetry in how common ancestry and natural selection are related to each other in Darwin’s theory. To get evidence for common ancestry, natural selection need not have caused any of the traits we now observe. But to get evidence for natural selection, Darwin needs to be able to think of present day organisms as tracing back to common ancestors.”

That last sentence is surely too quick. Yes, undoubtedly, and as Elliott brings out so well in his longer essay, part of Darwin’s case for natural selection presupposes common ancestry, as when he shows how natural selection might have brought the eye to such complicated perfection. But the relevant chapters belong, as Jonathan Hodge brought out in a classic 1977 paper, to the “adequacy” part of Darwin’s vera causa case for natural selection – that is, to the chapters showing that natural selection is powerful enough to do the causal work that Darwin wants to attribute to it.

But Darwin can address adequacy where he does only because, in earlier chapters, he has addressed the more basic question of existence. And he does that, as Elliott indicates, without presupposing common ancestry. The argument draws on an analogy with artificial selection. The Malthusian struggle for existence is an accumulating selector of variation in much the way, Darwin suggests, that the breeder on the farm is. But since the Malthusian struggle is so much more powerful, its effects will be comparably greater – resulting in new species, rather than mere varieties.

In incidental, foreshadowing ways, Darwin in these earlier chapters refers to common ancestry. But common ancestry doesn’t enter into the logic of the argument. And to that extent, the evidential asymmetry, for all its interest, looks less pronounced than Elliott makes out.

It may be helpful to distinguish two different questions here: (1) why did Darwin arrange The Origin the way he did; and (2) how does Darwin recommend prioritizing appeal to common descent and natural selection with regard to accounting for evidence and explanation. As for the first of these questions, I’m inclined to agree with Grant, in that it might be usefully answered by appeal to rhetorical strategy or history. For an answer to the second, it might be more useful to look at how Darwin himself employs explanations in The Origin. Specifically, I think that chapters six and seven are especially illuminating here, as they concern responses to possible challenges to his theory.

An example of what I think Elliott is asking about can be found in Chapter 6: Difficulties on Theory, p. 187 (of the 1st edition—facsimiles of which are freely available on Google Books):

This passage may present a few clues in how to answer Elliott’s query. Firstly, we might look to chapter six as an exemplar of how to consider evidence in the context of Darwin’s theory. After all, it (along with chapter seven) is dedicated to addressing possible difficulties with his theory, where he considers possibly confounding evidence (or lack thereof). This passage suggests that the best starting point for addressing many of these questions is, as Elliott suggests, common ancestry. (A point on which most contemporary systematists would surely agree!)

If one continues from the passage I cited earlier, there is a sentence that I think further supports Elliott’s general premise:

Notice here that priority is given to the theory of descent, as an explanation of the fact that the structure of the eye of an eagle is the product of natural selection.

So in chapters six and seven, Darwin relies on the two main features of his theory—Natural Selection and Common Descent—to answer the challenges of his imagined critic, and to demonstrate the greater utility of his theory against a design argument. And Darwin does this in a manner largely reminiscent of what Elliott describes here. But notice something else too, what are anomalies for the design argument are taken as evidence for Darwin’s theory; i.e., what needs to be explained away in an ad hoc way for design theorists, is predicted and expected under Darwin’s theory. So though Elliott is exactly right when he states that:

Perhaps Elliott does not go far enough. It is not just a question of how the two features inform evidential support for the other, what is at stake is what counts as evidence and data in biology at all.

So I largely agree with Elliott’s observations about the relation of the two aspects of Darwin’s theory and how they may provide evidential support for one another. But I think Darwin recognized this as well, and provides a model of this in his responses to the possible challenges his theory may face.

Not to go too far afield, but like Elliott, it is difficult not to consider what counts as a good mode of inference once we start down this path. Elliott asks whether parsimony ought to count as a good mode of inference, and I think that chapter six again offers us some insight into Darwin’s view on the general question of what counts as a good explanation. … Most notable here is the contrastive method (as Elliott has discussed in many places, most recently in his book Evidence and Evolution)—Darwin considers the difficulties that might be raised against his theory and considers how other possible theories might account for them. There are several things to notice about his: (1) not much stock is placed in simply being able to account for evidence within the scope of a theory. That is taken as a minimal criterion of a theory’s viability; (2) In order to be convincing, a theory’s ability to account for evidence must be made in contrast to other possible theories’ accounting of that evidence.

What does this tell us about any rule of inference as a good rule of inference in biology? Contrasting two (or more) theories’ ability to account for evidence is itself a rule of evidence, and how each of these theories account for that evidence also requires some commitment to a rule of inference as being good. So in chapter 6 we get a multi-layered approach to consideration of evidential support for Darwin’s theory. I won’t delve deeper into this, but again reference back to Elliott’s work and consideration of this mode of inference in terms of likelihood analysis.

Generally I am cheering Elliott on in his discussion of how NS and CA are related in Darwin’s ORIGIN.I phrase my support like that because I do not have the specialist knowledge required to contribute to his(E’s not D’s) treatments of likelihoodist theories of evidence or post-Hennigian phylogenetics.

1.The whole question of how those late chapters of ORIGIN (X-XIII in first ed) relate to the earlier chapters cries out for clarification. A point is sometimes made as follows.In those chapters, D cites all kinds of factual generalisations —paleontological,biogeographical, embryological etc and argues that these general facts evidence his thesis of CD ( common descent ) by means of NS, because CD+ NS explains them so well , so much better than rival explanations. However, does he really show that CD+X could not be made to look just as good evidentiallyt; where X is any other causation that produces gradual, adaptive, differentiationary divergence from common ancestors: Eg ‘Lamarckian’ inheritance of acquired characters.In other words does D ever show that the peculiar features of NS –the features that mark NS off from all other such candidate causes for such adaptive divergences –that those special features can uniquely get evidential support from these various facts by being the only or best candidate able do this explaining.My view is that Darwin did think he was implicitly meeting this challenge in those chapters , but I do not see him explicitly and sustainedly facing up to that challenge anywhere.I am not surpised then when some commentators read those chapters as often not engaging CA+NS at all, just CA on its own. Eliott alludes to this issue from time to time;it would be good to see a more sustained discussion.

2.On Elliott on NS as such in the ORIGIN ,I am very much in agreement , esp eg in his disagreeing with Bob Richards’ animistic Plotinian-Schellingian reading. However I do think Elliott needs to make some distinctions. He,E, tends to talk indiscriminately about ‘ evidnce for NS ‘. But that is too indidcriminate by a long way. E seems to accept a view now shared by many if not all exegeses of D’s argumatation in the ORIGIN;namely that D makes three independent evidential cases for NS in this order: a case for its existence, a case for its competence to cause indefinitely, prolonged and extended branching adaptive divergences , and a case for its having been resposible for most of the divergent adaptive descent in life’s past course on earth, as evidenced by biogeography ,morhphology etc.Now, E asks whether NS is evidentially independent of CA .Well,as Greg Radick indicates in his submission, how that query is answered all depends on which of the three evidence cases we are talking about.I agree with Greg in thinking that the existence case is evidentially independent from CA, but that the adequacy or competence case is not, nor therfore the resposibilty case.

3.So much for my main suggestion about E on D on NS.Next: E on D on CA. Here I am not sure how far I differ from E.So to sharpen the issues ,let me indicate how wide the gap between us just could be.

E’s articulation of what he calls Darwin’s principle (DP) is I think way to narrow in its focus on useles traits. Sure, as he shows ,D did invoke such traits as evidence for CA.But much more often D’s argument was not about traits as such, but about similarities or other commonalities. Why do all the placental mammals have in common absence ( until man took some there) from Australia,when they can thrive there if taken by man?We can not explain this common absence as due to a common adaptation to conditions only found outside Australia and so not within that area, because just see how well they do once transported there.So a common adaptation explanation for this common absence won’t do.But a CA explanation on does nicely: the placental mammal species all descend from a CA that lived outside Australia and no descendents have been able to get to the land of kangaroo without human help.

Now notice the parallel with d on the pentadactyl forelimb structure common to bats, monkeys, whales et al. This common structure is not credibly explained as due to comm adaptation to a common way of life with common uses, because the ways of life and uses –flying ,swimming , grasping — are not common.Faced with this failure of the common adaptation explanation, what does D do? Well, he notes, we could say that the common structure is due to a common idea in the Divine mind , but D says that is not even wrong.It’s not a scientific ex at all.So what does D say? He says that CA–think of sibs abd cousins — is a known cause ( a vera causa) of similarities in oprganisms: so CA is the best explanation for these similarities between bats, monkeys and whales in their forelinb structure.So that and all such structural resemblances–inexplicable as common adaptations–among plants and animals are so many eveidential supports for CA.

Now, note,D does hold that that pentadactyl structures was first produced in the remotest ancestors as an adaptation due to NS .The structure was then an adaptation and still is, these forelimbs are still useful and are so thanks to that structure.But there is no common adaptation explanation that can be given for its being common to these diverse species–bats, whales , monkeys , becase it is no meeting the same adaptational needs and uses among them.Hence CA ( common ancestor) not CA ( common adaptation) is what they evidence. for nonadaptive resemblabces , then , invoke CA, but for the adaptive differences eg between monkey’s hand and bats wing invoke NS. So the decisive contrast is not between two sorts of traits, but between some resemblances and some differences.

If all this is pertinent then E’s account of D’s principle, does not do justice to D’s position on these issues.And that is crucial becase it was just such issues tha got D into CA originally and before he came up with NS, when indeed his package was not CA + NS, but as all close readers of the pre-NS notebooks now agree, his package was CA + Lamarck-style inheritance of acquired characters causing in the log run branching, gradual , adaptive divergenges.

(A conjecture as to why E has gone astray here:reading too much Steve Gould,onetime Leeds student, late at night.How come? SG often says history is evidenced by imperfections more than perfections ( NS is the way round perhaps).CA is about history, so CA is evidenced by imperfections.Suggestion to E: look again at D on biogeography and on morphology and, yes, the use eg of pentadactyl forelimbs in taxonomy, and see the parallels in how CA comes in for D in these places.

4.Why did D write ORIGIN as he did?We know why.( That’s academic english, of course, for I think I showed why years ago!.He did so because his very first version of what would become ORIGIN was what ? The sketch of a comprehensive zoonomical syten in the first 2 dozen pages of Notebook B , written in July 1837 months after D was a CA man but when his theory of adaptive divergence was Lamrckian and not NS because NS was still a year and a half away. And why does that sketch have the structure it does, so like the structure later given the ORIGIN?Because D knowingly gave it the the structureb Lyell gave to his exposition of Lamarck’s system ( a very different sructure from Lamark’s own.) Why did Lyell give it that structural ordering? Because h9is prime interest was in whether there are known causes for species origins in branching transmutations.He decides , no , of course. His protege,D wants to reopen the case .So, his sketch starts with known causes for species transmutations ,not with CA. So, like ORIGIN later ( and like Lyell’s’s version of Lamarck earlier) that sketch only gets to the irregularly branching tree after the case for true causes for species formations is in place.

Stand back and look at Newton’s PRINCIPA and Lyell’s PRINCIPLES and D’s ORIGIN.What structuring do thay all follow: Do the nonexplanatory evidencing for your causation first , and the the explanatory evidencing last.Ie do evidence for existence and adequacy, first , the evidencing from facts that are NOT the ones you will later use your case to explain, do this explanatory-use-independent, this nonexplanatory evidencing; THEN go on to the explanatory power-use dependent evidecinhg .Darwin did as he did because Lyell and Newton had done what they had done …Herschel helped Darwin to appreciate this double precedent.So ,it’s because of N and L and H that ORIGIN was not written backwards but in the right order for a book coming after N and L.Get D’s order in the historical succession right and you’ll see why there could be only one right order for him to follow in evidencing NS without CA and then NS + CA.

I would raise three issues regarding Elliot’s Puzzle.

Elliot distinguishes two questions:

(1) Must one be able to judge whether there was selection for a trait in order to determine whether a trait shared by two species is strong evidence that they have a common ancestor?

(2) Must natural selection have been an important influence on trait evolution for there to be strong evidence for common ancestry?

He says that Darwin answers “Yes” to (1). It strikes me, then, that the answer to the question “Why did Darwin write the Origin by front-loading natural selection?” is simply that Darwin thought the answer to (1) was “Yes” — that is, he thought one must be able to judge whether there was selection for a trait in order to determine whether a trait shared by two species is strong evidence that they have a common ancestor. The real puzzle, then, seems to be why Darwin thought (if he did) the answer to (1) was “Yes.”

Two related issues arise for motivating Elliot’s Puzzle. First, in addition to (1) and (2), I would also point out that the answer to

(3) Must there be useless or deleterious similarities between species for there to be strong evidence of common ancestry?

is also “No.” Useless similarity between species is only one type of evidence presented in the Origin in favor of common ancestry. Other types of evidence play an equally important role in establishing common descent. Some of them (such as certain progressions in the fossil record) invoke adaptive modification of a lineage. Others (such as branching) do explicitly require natural selection.

Second, Elliot writes as if common ancestry is the only reasonable explanation for neutral or deleterious similarities. I agree, but there were a number of competing explanations for this phenomenon at the time the Origin was written (such as Owen’s archetype). A world saturated with neutral and deleterious similarities may be our idea of epistemological paradise so far as the hypothesis of common ancestry is concerned, but I wonder what biologists of the mid-19th century would have inferred from such a world. An important question for Elliot’s project to address, so it would seem, is whether the probability of common ancestry as an explanation for neutral or deleterious similarities was raised (relative to that of other available explanations) if one assumed natural selection as the cause of adaptation. And if so, why? As Elliot points out after the quote from the Origin, Darwin seems to have thought so.

[One thing I meant to include at the end of the penultimate paragraph]

It might be useful to think in general about how strong the case for common ancestry would have been if Darwin had made no attempt to explain adaptedness. One historical point that appears to motivate Elliot’s puzzle is the fact that common ancestry was more widely accepted after the publication of the Origin than was natural selection.

I am grateful to the commentators for their insights. In my posting , I mainly discussed the evidential relationship of common ancestry and natural selection in Darwin’s theory; at the end of what I wrote, I posed a question without attempting to answer it – why did Darwin write the Origin with natural selection developed first and the big picture of common ancestry getting introduced only later? This is a question about Darwin’s rhetoric. I’ll discuss what my commentators say about this question after I address some of their other ideas.

Jon Hodge and Greg Radick both point out, as I did, that Darwin has an argument for the existence of natural selection that does not depend on common ancestry. This is his Malthusian argument. They also point out that Darwin’s argument from artificial to natural selection does not depend on the fact of common ancestry. This, of course, is correct. Notice that these two arguments leave open which traits evolved by natural selection and why they did so. It is here that Darwin uses the fact of common ancestry to think about natural selection. When I said in my posting that “to get evidence for natural selection, Darwin needs to be able to think of present day organisms as tracing back to common ancestors,” I wasn’t being careful enough.

Matt Haber emphasizes the importance of thinking about Darwin’s argument contrastively. In defending common ancestry + natural selection, what theories was Darwin arguing against? One of them was special creation. Another is a kind of “hyper-adaptationism,” according to which every organism is perfectly adapted to its environment. It is clear how biogeographical data, imperfect adaptation, and the like are evidence against the latter. It is less clear how Darwin can have evidence against the former, especially given his remarks that creationism makes no predictions about what we should observe. Darwin seems to flip back and forth between thinking that special creationism is a testable theory and thinking that it is not.

Jon Hodge asks whether Darwin ever argues that his own theory of CD+NS is better than an alternative theory CD+X. Here CD is common descent, NS is natural selection, and X is some alternative to natural selection such as the Lamarckian idea of the inheritance of acquired characters. I know of one place where Darwin does this. It is in his discussion in the Origin of the evolution of worker sterility in social insects. I discuss Darwin’s reasoning here in Chapter 2 of my book Did Darwin write the Origin backwards? The chapter is about Darwin’s views on group selection.

Jon Hodge says that Darwin has other evidence for common ancestry besides nonadaptive similarities. I don’t disagree. I didn’t intend my discussion of Darwin’s Principle to be a full account of Darwin’s picture of the evidence. In Chapter 1 of Did Darwin write the Origin backwards? I describe some exceptions to Darwin’s principle; there are cases in which adaptive similarities provide strong evidence for common ancestry and other cases in which nonadaptive similarities fail to provide strong evidence for common ancestry. Hodge says that the pentadactyl forelimb is an adaptation that still is useful, but it nonetheless provides (strong?) evidence for common ancestry. I agree. Hodge also mentions a fact of biogeography – the fact that no mammals existed in Australia until human beings arrived and brought some nonhuman mammals along with them – and says that this is evidence that mammals have a common ancestor. I discuss biogeographical evidence for common ancestry in Chapter 3 of my book Evidence and Evolution. It is interesting to consider whether and why shared morphology and shared geographical location are different kinds of evidence in connection with the problem of testing common ancestry.

Chris Haufe says that one doesn’t need neutral or deleterious similarities to get evidence for common ancestry. I agree. Chris gives the example of a fossil sequence that shows adaptive modification. I discuss the evidential meaning of “intermediate fossils” in Chapter 3 of Evidence and Evolution.

So why did Darwin give natural selection top billing in the Origin? Grant Ramsey says that Darwin wanted to start with an observation that is indisputable. I agree, but it is indisputable that some organisms have common ancestors. We know this from human family trees and from the records kept by plant and animal breeders. Why didn’t Darwin start the book by building a case for common ancestry in the same vera causa style that he used to build the case for natural selection? Grant also says that common ancestry would have been a bitter pill for Darwin’s contemporaries to swallow. Grant is right; what makes the pill bitter is the idea that human beings share ancestors with monkeys. We know that Darwin wanted to avoid discussing human evolution in the Origin. Maybe this was part of his reason for not starting the Origin with his big picture of common ancestry. Grant also suggests that Darwin had a stronger case for natural selection than he had for common ancestry; maybe Darwin led with natural selection because this was his strongest suit. It’s hard to compare how well common ancestry and natural selection were supported by Darwin’s data, but we do know that Darwin’s audience got on board with common ancestry far more readily than they did with natural selection. Were they misreading the evidence?

Peter Gildenhuys and David Baum each point out that Darwin needs a mechanism to explain how adaptation and diversification could have arisen. I agree, but this doesn’t explain why natural selection comes first in the Origin. Leigh Van Valen notes that adaptation was the “glaring hole” in naturalistic accounts of life’s diversity – how could this be explained without divine providence? Of course, there was the influential Lamarckian idea of inheritance of acquired characteristics, at which most of us now look askance. Darwin’s contemporaries mostly did not. But even if the origin of adaptation was the gaping hole that Leigh says it is, how does this explain why selection comes before common ancestry in the Origin?

Joel Velasco says that “natural selection lowers the bar for how much evidence is needed for specific arguments for common ancestry.” Joel’s idea is that natural selection comes first because it helps Darwin make his case for common ancestry. As David Baum also notes, the incredulity that readers might experience at hearing that spiders and flamingos have a common ancestor might be lessened if a mechanism were described that can lead descendants to diverge indefinitely from their ancestors. This also bears on Chris Haufe’s question of whether common ancestry as an explanation of nonadaptive similiarites is made more plausible by natural selection’s being a cause of adaptive similarities.

Emanuele Serrelli suggests that Darwin put selection first in the Origin because he wanted to begin with the mechanism of change. Jon Hodge reminds us of the important arguments he has developed in earlier publications that Darwin followed Herschel’s codification of how Lyell and Newton argued. The goal of science is to establish the “true cause” and one begins a scientific argument by describing cases in which the existence of a putative cause has actually been observed. But what were the effects whose causes Darwin sought to identify? Hodge, like Van Valen, takes the title of Darwin’s book at its word – the mystery of mysteries is the origin of species. For them, Darwin’s problem is to identify the cause of there being different species – what gives rise to the diversity we observe? The answer to this question is natural selection. Selection causes diversity; common ancestry does not. I agree that if the main goal of the Origin is to explain species diversity, or adaptation, then it makes sense to give natural selection top billing. But if Darwin’s goal is to argue for his theory – which is the theory of natural selection plus common ancestry – why should natural selection go first? Here I am reminded of an 1863 letter to Asa Gray in which Darwin wrote that “personally, of course, I care much about Natural Selection, but that seems to me utterly unimportant, compared to the question of Creation or Modification.”

Given that Darwin’s theory has two parts, and assuming that Darwin’s goal is to defend both of them, why did Darwin put natural selection ahead of common ancestry, both in the Origin, and in earlier manuscripts? The answer I develop in Chapter 1 of Did Darwin Write the Origin Backwards? is that Darwin thought that selection causes extinction and branching. The upshot of extinction and branching is the tree of life – the fact the extant organisms trace back to one or a few common ancestors. Selection comes before common ancestry in the Origin because selection has causal priority.