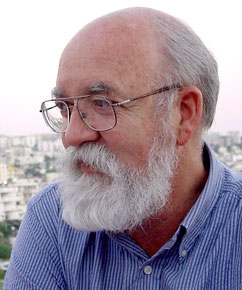

Daniel C. Dennett

Anybody who has lived through the ordeal of watching an elderly parent die by inches knows that this is no way to end one’s life. Given that death is (still) inevitable, which would you prefer for your last months on earth: being struck by lightning at some point before you began losing your faculties, or an indefinitely long period of decline, during which you would gradually become unable to perform the simple actions of life and participate meaningfully in conversation or decision-making? Almost everyone I have talked to strongly prefers the sudden-death option, but lightning almost never strikes, and many thinking people have a reasonable distaste for any contrived departure suicide or assisted euthanasia that necessarily involves decision-making by themselves or others. Why? Because wherever there are such decisions to be made, about quality of life, or degree of impairment or suffering, there are inevitable opportunities for undesirable motives to creep into the mix: greed or impatience or on the side of the soon-to-die guilt about staying alive beyond one’s allotted span. Any practice that became widespread and socially acceptable would, one fears, carry with it an irresistible pressure towards too much self-consciousness of the wrong sort. As the philosopher Kurt Baier once quipped, echoing Socrates, “The unexamined life is not worth living, but the over-examined life is nothing to write home about either.” We don’t want to end our days wondering if everyone around us is glancing at their watches and sizing up our remaining faculties against some unstated but all too present threshold. The recognition that one has “lost a step” on the various playing fields of life is bad enough without having to consider how it affects the bottom line on the great spreadsheet of one’s life.

So it would be better, would it not, for the power of decision and the concomitant obligation of making a reasonable judgment to be taken out of the hands of everyone: family, friends, “society” and even oneself. How could this be accomplished? How could we engineer lightning strikes without specific human intervention and without chaos? By designing and installing in everyone a robust system of whole-body apoptosis. Apoptosis is programmed cell-death. As Wikipedia notes:

Apoptosis is a process of deliberate life relinquishment by a cell in a multicellular organism. It is one of the main types of programmed cell death (PCD), and involves an orchestrated series of biochemical events leading to a characteristic cell morphology and death. The apoptotic process is executed in such a way as to safely dispose of cell corpses and fragments.

In contrast to necrosis, which is a form of traumatic cell death that results from acute cellular injury, apoptosis is carried out in an orderly process that generally confers advantages during an organism’s life cycle. For example, the differentiation of fingers and toes in a developing human embryo requires cells between the fingers to initiate apoptosis so that the digits can separate. Between 50 billion and 70 billion cells die each day due to apoptosis in the average human adult. For an average child between the ages of eight and 14, approximately 20 billion to 30 billion cells die a day. In a year, this amounts to the proliferation and subsequent destruction of a mass of cells equal to an individual’s body weight.

We could arrange to have a human body switch itself off quite abruptly and painlessly at a time to be determined. Almost nobody would want to know to a near certainty the exact day and hour of their death, and the reasons why are made vivid in any number of death-row dramas. So a humane system should introduce a substantial element of randomness, elongating the bell-shaped curve of programmed death-knells over a period of, say, five years. Then you would know to a moral certainty that if you hadn’t already died of some other cause, then at some unpredictable time between, say, your eighty-fifth and ninetieth birthday, you would quite suddenly drop in your tracks, perhaps in the middle of a golf swing, or while trying to finish writing your latest novel, or even while making love.

The implications and repercussions of such an attempt to engineer programmed body-death into ourselves and our descendants are mind-boggling. We can begin to get some grip on the pros and cons by sketching out the specs for a simple version that may need substantial tweaking:

Whole-body apoptosis 1.0. We install in every human being and in every subsequent human embryo a system that ensures the swift, painless death at some randomly determined time between the age of 85 and 90, if death from some other cause has not already occurred.

How could we accomplish this? The technical details are important, since each conceivable means to this end has some drawbacks or weaknesses associated with it, and we can expect these to be magnified by all manner of human disagreement. It is quite possibly true — let’s think about it — that the ethical and political problems that would beset any such system would make it essentially unimplementable: you can’t get there from here without committing some ethically unacceptable or politically infeasible act. In that case, we’ll be stuck with our current dismal ways of dying, but let’s explore the territory to see what might be possible.

The technical project divides quite naturally in two: providing a system for the already alive, and genetically engineering a system for subsequent embryos.

The latter is a problem for “evo-devo” (evolutionary-developmental) biologists, who are beginning to understand the cascades of biological clocks that turn on and off various developmental processes. We know quite a lot about how our biochemistry arranges the timing of such events as puberty and menopause, and we even know that human culture has already “interfered” successfully with such a process in the distant past. Unlike all other mammals, many of us human adults can digest raw milk, because natural selection has produced a gene that turns off the machinery that would otherwise turn off the production of lactase at weaning. So common is this genetic revision in our species that we refer to those who lack it as “lactose intolerant” instead of referring to the rest of us as, say, “digestively infantile”! It was the human practice of dairying, culturally evolved and transmitted, that provided the selection pressure for this genetically transmitted adaptation.

What natural selection can accomplish over a few thousand years (agriculture began roughly 10 thousand years ago) ought to be within the grasp of genuinely intelligent designers over a few decades. I see no reason why we could not now genetically engineer an enzymatic time-bomb that would reliably explode at some time late in life. Perhaps it would suddenly start spewing endocurarins into the bloodstream, stopping all voluntary muscle movement and hence suffocating the body more effectively than any pillow. (I am making up the term “endocurarin”, inspired by the naming of endorphins, endogenously created opioids that produce such phenomena as the runner’s high. Curare, the legendary blow-pipe dart poison that swiftly paralyzes the muscles leading to asphyxiation, led to the development of muscle relaxants for surgery — D-tubocurarine, for instance — that would kill the patient were it not for the respirator that accompanies its administration.) Might some genes be designed to generate endogenous curare? Could we perhaps import the relevant genes from poisonous plants or frogs and adapt them to serve this purpose in our bodies? (We can already make a tobacco plant that glows in the dark because it has firefly genes spliced into its genome.)

Or perhaps we could engineer a gene that, when triggered by a biological clock, would produce some kind of endogenous nerve gas, or something that would lead to a catastrophic collapse of blood vessels, causing a massive stroke and brain death. I leave further exploration of these and other alternative physiological death-delivery systems to the experts, noting only a few of the obvious desiderata: the method employed should be highly reliable, inscrutable (there is no practical way of assaying the system to figure out exactly when you will die), utterly non-toxic earlier in life, as tamper-proof as possible, and with no seriously debilitating genetic side-effects. (We will explore the myriad non-genetic side effects of such a system in due course.)

What, then, about those already living? What, for instance, would I choose to have administered to me, now, in order to achieve this effect at some point roughly 20 years down the road (I am 65 as I write this). The simplest system, perhaps, would be a time-release poison capsule of the sort now well known to medicine, but with a 20-year (± 1800 days) fuse. This could be implanted like a pacemaker, and surrounded by tamper-proofing (if you try to remove it surgically, it blows up prematurely). Better might be the injection of a bio-engineered drug that would begin accumulating something in the bloodstream that would suddenly (after 20 years plus) go haywire. Needless to say, the reliability and non-toxicity of any such introduction would have to be very, very high before I would volunteer for it, but I imagine it would be only moderately more momentous a life decision than a vasectomy, or undergoing some optional surgery with a low probability of a fatal outcome. We are becoming used to making such decisions, and for good reason. They reliably solve important life problems with acceptable levels of risk.

But how many others would share my attitude? What public service campaigns, educational programs, political debates and discussions could conceivably engender a majority, let alone a consensus, to adopt such a system? (I am going to set aside, for now, the interesting and important economic issues concerning health insurance and life insurance, and the impact such a system would have on them, since I want to stress that this is not a proposal designed primarily to save the taxpayers money or preserve the inheritances of the living, but a proposal designed to reduce the large and inevitably growing amount of pointless suffering that our other technologies have in store for us if we don’t change something.) Given what we know about the controversies surrounding fluoridated water and compulsory vaccination programs, we can expect a firestorm of debate about any such proposals. But those campaigns also teach us a great deal about how to present such issues and how not to do it. The “tampering with God’s will” objection is getting ever more threadbare and unconvincing with overuse, and people are beginning to appreciate the benefits of intervention, and adjust their principles and creeds to accommodate it.

“Aha!” say the diehards (as we may come to call them). “We now see that we were right to dig in our heels about all these earlier technological enhancements! They paved the way for this horror of horrors: programmed death!” But technology that they have already come to accept continues to make unprogrammed death ever harder to contemplate and endorse — think of poor Terri Shiavo — so I think the diehards will attract fewer and fewer supporters.

What, aside from tradition masquerading as “principle,” stands against such an innovation? Who would be harmed by it? People who otherwise would have lived healthy lives till they were a hundred? This raises a sensitive issue about which people may disagree: is 85 too young or too old? Only a few decades ago, spry 90-year-olds were quite rare, but not today. Should the programmed kill-by date be moved up to 95 or even 100? That would give quite a few healthy oldsters a few more years of life worth living, but also would fail to kick in soon enough to forestall a lot of suffering. How do we balance the increase of suffering against the non-suffering lives of a few? Clearly, there is no point in adopting such a system unless it actually does cut down most people “in their prime”! If you would prefer to die by lightning bolt while you are still effective and healthy, the price you must be willing to pay is foregoing some years or months that would have been just as effective and healthy as your last days. We haven’t had any experience thinking of our lives in terms of diminishing returns, and many will no doubt still feel that more days of life, no matter how painful and confused, is always better than less. But perhaps we can begin to contemplate, and take seriously, the idea that just because we could arrange to live to be 100 (or 120!) we really have no right to use up so much more than our fair share of the world’s resources and amenities.

This is a new and unsettling way of thinking of your life, and it is hard to say how people would adjust their expectations to the recognition of the realities of the system. Would people plan to go out in a blaze of glory? Would those who could afford it set aside just enough to tide them over (in health) for a few years, and then give away the rest, so that they would get to enjoy the delight and gratitude of their heirs? Would people start a tradition of having 85th-birthday-party extravaganzas that celebrated the life and deeds of people in much the way funerals do today, but with the not-yet-departed one present? And what would the lame-duck period after 85 be like? One would still have all one’s rights, and could go right on working or playing as one chose, perhaps living a bit more riskily, perhaps not. It should be remembered that we already know that we’re all going to die, and quite soon, if we’re in our eighties. This innovation would sharpen an existing anticipation, not create something entirely new.

One of the most interesting objections I have provoked in recent discussions is the suggestion that this policy, if adopted, would rob us of precious opportunities to prove our strength by enduring suffering. One friend told me that she never appreciated her mother at all until she nursed her through an agonizing death and saw her indomitable will and dignity under horrible conditions. If this policy had been in force, her mother would have died unappreciated. But that suffering is a huge social cost to pay for such occasional redemptions, I would say. Besides, the same line of thought could be used to disallow the pain-killers now routinely given in whatever doses are needed to do the trick, on the grounds that we were depriving these poor souls of golden opportunities to prove their fortitude to skeptical family members and other onlookers. Yes, there would be less employment for end-of-life caregivers who now find their life’s meaning in taking care of semi-comatose, incontinent, incommunicative old folks. Some might be dismayed by the waning of this tradition, but not many, I surmise. And there would still be plenty of suffering to witness and relieve, since nothing in this proposal would guarantee that people wouldn’t die terribly prolonged deaths at age 60 or 70 or 80 of all manner of diseases and conditions.

Another objection has often arisen, put very well by a referee for this [Artifact] journal:

Dennett observes that “spry 90-year-olds” are less rare today than several decades ago, but goes on to offer a diminishing returns argument that says that (a) dying in one’s prime is a price worth paying to avoid a lingering, painful and confused end, and (b) that living to 120 or so would involve using up more than our fair share of the world’s resources and amenities. However (a) & (b) are somewhat separable: if the person is increasingly impaired then extending life to 120 (for example) would involve declining quality of life and (perhaps) wasteful consumption of resources. On the other hand if the person remains healthy and active then they have gained 30 years of good quality life compared with the fate of previous generations. Arguing that a healthy 30 years should be abbreviated to save resources looks like a complex job from a moral standpoint, and in any event if the person is healthy then they might well be productive, generating a net social gain for the extra years, just as major extensions to lifespan have had adaptive benefits in past human evolution. To be reasonable it looks like the programmed lifespan must fairly closely match the healthy lifespan. Implementing such a system, however, requires estimating 80 (or perhaps even 120) years into the future, in the face of the possibility that in the meantime new developments might prolong healthy life further. Workarounds that address the problem might be possible (perhaps capacity to reset approximate time of death?), but this adds significant extra complexity.

Yes, indeed, we could use technology to fine-tune the system, to monitor various plausible measures of quality of life in both individuals and populations, so that apoptosis could more optimally track actual mean rates of decline — or even rates of decline in individuals — so that apoptosis could be customized in any of a dozen ways. A mathematical model of expected healthcare savings under variable regimes of apoptosis has already been sketched. But while these might be possible, and might be desirable improvements, they cut against the spirit of my proposal, which is to use technology to remove this issue from our decision-making options and the incessant monitoring that would rationally follow in its wake. To give a heightened sense of the flavor of my proposal, consider how you would feel about adopting elaborate falling-in-love-monitoring technology, which could take the guesswork out of romance (and prove its value by a diminished divorce rate, yadda yadda yadda). We should pause to take seriously — very seriously — the prospect of protecting some aspects of our lives and deaths from management, and thereby reframing our landscape of decisions. Why should we devote so much of our R&D budget to finding ways of extending life? We aren’t similarly obsessed with ways of making our descendants taller or stronger or smarter. Knowing that you could expect only so many years of life might focus your mind, and will, wonderfully.

The idea of whole-body apoptosis opens up vertiginous vistas on the meaning of life and suffering, the unexamined assumption that more is always better than less, and the prospect of being able to live out your remaining days relatively confident that your survivors will not have to set aside memories of a pathetic decline in order to get to the memories of you that matter. What would you trade for that? I’d trade any number of years over 85.

CODA: Let me add an improvement to my proposal for whole-body apoptosis that is obviously desirable, if only for safety reasons. Any “lightning strike” programmed death should be unpredictable from a temporal distance, for the reasons I offer, but you should be provided with a ten-minute advance warning to give you an opportunity to drop the sails and anchor, pull off the highway, pull up your pants, call your family and friends, or, for that matter, shoot your enemy or burn all your records. This friendly amendment was first suggested to me by Paul Seabright.

This paper, presented to the National Humanities Center’s 2007 conference on Autonomy, Singularity, and Creativity, is reprinted – with the coda added – with permission from Artifact 1, 4 (2008).

Fascinating idea. I would point out though that voluntary euthanasia, or better suicide options for everyone, would be a good start in the right direction.

As far as human genetic engineering is concerned, it seems there are more relevant applications. Why not reduce the average human pain sensitivity by 20-30% and/or increase average happiness respectively to make life better during the 80 or so years it’s going to last? (for a long-term vision, compare http://www.hedweb.com/abolitionist-project/index.html)

It is also worth pointing out that a genetic time bomb may be very unpleasant for those born with it if effective longevity solutions are discovered during their time, especially if the time bomb can’t be switched off…

PLANNING OBSOLESCENCE

More options: How about choosing the moment on the fly, based on your condition and prognosis in real time? Or pre-specifying the objective medical criteria on the basis of which you would like it to be decided when the euthanasia should to be done (while you’re asleep)? (But wouldn’t many people prefer to be able to say goodbye?)

Why apoptosis? Nocturnal barbiturate administration would do the trick, if the criteria were objective and reliably (and verifiably) followed. (Apoptosis just adds a needless further layer of sci-fi on the problem, which is merely to determine when the euthanasia should take place. Surely it’s better to make that that decision an objective criterion-based one rather than simply an a-priori time-based one?)

Are death-row inmates (whether guilty or innocent) representative of the rest of humanity? Surely there are many people and reasons for wanting to know when. And even if one does not know, the question is whether the cut-off should be actuarial clock-triggered or substantive criterion-triggered. (Determining the right criterion – or, for that matter, the right chronometry – are another matter, and that’s probably where the real substantive issues reside.)

Why between 85 and 90, or between any t1 and t2? Is the idea that the interval is an absolute, universal one, that fits all of humankind? If not, then surely it is what other factors (e.g., health, performance capacity, desire to stay alive…) determine the individuals’ time-window that matter far more than keeping the moment within the time-window unpredictable.

By basing the euthanasia point on individual, objective criteria, not a-priori timing.

There’s decline and there’s decline. Some people would put up with some bodily deterioration as long as they remained mentally sharp. None of these things is predictable, for an individual, from a-priori timing alone. That’s just population statistics, and if we’re to be treated according to those, then we may as well not see doctors when we are ill: just type in our age and symptoms, or perhaps just our age (so we can be treated automatically for its most common illness)!

If we are to reason along those lines, it’s not just our right to live out our years that must be subordinated to the rest of the planet’s needs, but what we have a right to whilst we’re alive (and others are wanting). There’s much to be said for (and against) thinking along these general lines, but it has another name than euthanasia or apoptosis. And the management of how long people are entitled to live will be far less consequential than the management of other entitlements (such as wealth, property, reproduction rights, and perhaps even how we spend our days and use our capacities).

That objection conflates the question of euthanasia itself with pre-timed pop-off. And it is an example of one of the most sordid and sociopathic justifications for withholding euthanasia (reminiscent of an equally noxious credally based one): Let them suffer for the good of their souls (and mine).

Well, fine, in the cases where “their” and “mine” are co-referential. (In other words, where I’m the one who decides I’d rather stick around and suffer.) But that’s the luxury problem, while there are so many who would rather not stay around and suffer, but are not allowed or able to do anything about it.

Better still, once we’ve figured out a better way of “customizing” the hour, forget about the apoptosis and just use nocturnally administered barbiturates…

And actuarially pre-planned apoptotic obsolescence is a protection from management?

That’s an entirely different matter, completely independent of pre-planned obsolescence.

Any updates on this view, now that another half-decade has gone by? The criteria for such decisions are of course personal matters, but I, for one, think the world would be far, far better off with Dan Dennetts staying around as long as they are compos mentis, than by doing them at an appointed age so as to stretch strained old-age pensions one epsilon further. If we’re going to contemplate sci-fi fantasies, looking for a way to engineer apoptosis for pre-programmed death seems to me far less to the point than looking for a way to convince people to limit reproduction, become vegans, and convert to a sustainable way of living.

But Dan’s essay can also be taken to be addressing a far more important and urgent matter than pre-programmed pop-off, namely, euthanasia itself. The worst thing about the status quo on death now is the fact that most people cannot choose to die, even when they wish to. Surely before we can have consensus on pre-programmed pop-off for all (whether or not they want it) we must first agree to allow those who do want to die, now, to do so. Yes, there are complications and risks of abuse that need to be taken carefully into account, but the current status quo is cruel, unjust, and irrational.

Compassion and Complacency, Sympathy and Sociopathy

Laws are rational base-camps on the slippery slopes of life

Sociopathic Sanctimony

Mandatory and Voluntary Whole-Body Apoptosis

Dennett’s provocative proposal pushes us toward a deeper understanding of end-of-life decision-making, the significance of death, and personal liberty.

As a matter of social policy, we could make the action of whole-body apoptosis (WBA) either mandatory or voluntary, i.e., either forcing people to submit to, or letting them voluntarily submit to, the appropriate physical requirements such that WBA occurs in the designated period later in their lives. Mandatory WBA appears to be Dennett’s proposal (what he calls ‘Whole-body apoptosis 1.0’). I suggest that both options raise important problems. However, mandatory WBA has the distinct problem of restricting individual liberty whereas voluntary WBA enhances liberty, specifically liberty regarding end-of-life decision-making. So, if we were to accept one of these, I suggest voluntary WBA (call it Whole-Body Apoptosis 2.0). First I will address some general problems for both mandatory and voluntary WBA. Second, I will address the question of liberty in relation to WBA and euthanasia (the relationship between euthanasia and WBA is alluded to in comments by both Hedonic Treader and Stevan Harnad).

Regarding general problems for both mandatory and voluntary WBA, the apoptosis event could occur at a very inopportune moment in the five-year span, causing the subject to incur great loss of potential value to herself or others (perhaps a missed moment of self-discovery, or other activities that Dennett alludes to such as finishing writing a novel). Our futures are full of opportunities, and WBA could cut nearly five years out. It is all the more devastating to know that it did not have to be this way. Furthermore, the apoptosis event could be quite dangerous, if one were engaged in actions in which others’ well-being or very lives depended on the subject (e.g., driving, spotting someone lifting weights). In the “Coda” section, Dennett amends the view so that the subject has a ten-minute warning. But this might be insufficient if one is driving a long, narrow road in the mountains with no pull-outs, for instance. Perhaps it should be fifteen minutes, or an hour, but extending the warning period seems to defy the point of WBA. People could refrain from all such potentially dangerous actions, but thereby diminish freedom and valuable opportunities. (Note that the same possibly dangerous outcomes exist in a non-WBA situation; but in a WBA situation, there is one more chance of this happening, and the subject knows it will occur at some point in that five-year span.)

An emotional cost also comes with either mandatory WBA or voluntary WBA. A designated time period for the apoptosis event precludes the (biological) possibility of living beyond that period. But, for some individuals at least, the possibility of personal immortality, in whatever form or fashion one dreams of (even if extremely unlikely), or persisting beyond one’s ‘allotted time’, generates hope: the hope of future opportunities, completing projects, etc. This possibility and the hope it generates partially drives some people to push on, thus yielding more value for the self or others.

Regarding the question of liberty, mandatory WBA clearly curtails individual liberty, foremost on the question of whether or not to die by WBA. But a policy allowing voluntary WBA enhances personal liberty. Version 2.0 of WBA makes this one of several voluntary ending-of-life options. But, as other commentators have mentioned, why not advocate for rights to engage in voluntary active euthanasia instead? Voluntary active euthanasia (‘active’ referring to a direct action that kills the subject, such as the injection of a lethal chemical), is safer for others (preventing the potentially dangerous outcomes mentioned above), less shocking (in the moment) to others, maximizes self-control capacities, and maximizes opportunities to engage in valuable activities.

Both voluntary active euthanasia and WBA are exercises of personal liberty and control over one’s well-being, yet convincing society to adopt voluntary WBA as morally permissible seems more difficult than convincing society that voluntary active euthanasia is permissible, a belief that has substantial traction already. Voluntary active euthanasia at least gives a person additional opportunities for valuable experiences before the time of death while equally diminishing the suffering (if carried out at the right time). Granted, the burden of decision-making for voluntary active euthanasia remains, but the emotional cost of this burden may seem insignificant to some individuals compared to the benefit of additional opportunities and experiences that voluntary WBA may erase.

As Dan says, the technical details are important. In particular the mechanism of causing death must be as “as tamper proof as possible”. Which raises a concern. Human ingenuity being what it is, and the profits to be made so enticing, someone is bound to come up with an effective antidote to apostosis. The antidote – like snake anti-venom – might work fast enough to be able to save the doomed person if given as soon as the ten minute warning comes. Assuming you could afford to purchase it (perhaps on the black market), wouldn’t you want to carry this antidote with you all the time after age 85, just in case? If you did have it available, would you actually use it? How would you justify doing so – to yourself or to the world?

Twenty years ago I wrote a story titled “The man who took his own death”. In the story the man, who is chosen at random, is given a drug that will kill him in exactly seven days time. But an antidote does indeed exist, and what the victim has to do is to persuade a jury of his peers that he should be given it. The jury meets every night to consider his arguments as to why they should intevene to save his life – the life of someone who will otherwise die. The story can end several ways. The philosopher Bernard Williams, whom I consulted on the ending, said that no one could make the case that that their life has intrinsic value, so the victim has to die. Dan, whom I also consulted, said that everyone could make that case, so he has to live. But the man in my story was in his 40’s. What if he is 85?

Another issue. Studies of happiness show that, as people grow old, unless and until they become ill or incapacitated, their general level of contentment goes on rising, even as the certainty of death approaches. I have written recently, in my book Soul Dust, about death as the “ultimate betrayal” of human hopes for the continuity of the individual soul. Dylan Thomas, addressing his dying father, called on him to “Rage, rage against the dying of the light.” But the reality seems to be that this is a young man’s prayer. Old people are surprisingly content to go quietly. I wonder about the evolutionary psychology of this. Since an old person raging against death does himself no good and is likely to be disruptive and distressing to those still living, maybe there has been selection to make people acquiesce (as an act of kin altruism).

And one more point. I’d say that to make the apostosis programme acceptable to the public, it would help if it were dressed up with a bit of ritual mumbo jumbo. Perhaps it should be made out to tie in with the rhythms of nature. One way of doing this would be to introduce a symmetry beween birth and death by having the warning of death come not ten minutes but nine months before the due time. The doomed person would then go through a period that could be celebrated as “anti-gestation.” (No doubt there would soon be self-help manuals available, along the lines of “What to expect when you’re expecting”.)

It is difficult for me to react in writing to these comments in the wake of the untimely death of my friend Christopher Hitchens, but now that I’ve begun to make my peace with a world which is Hitchless, I realize he would want me to deliver as clear-eyed and vivid a response as I can muster. If only I could emulate his wit and his trenchancy.

There is a pattern to be found in these comments, and I can’t decide whether to be amused or bemused by it, frustrated or vindicated: the main point of my essay has escaped comment by all. I was not proposing whole body apoptosis (WBA, as William Bauer has abbreviated it) as an alternative to voluntary active euthanasia or any other kind of euthanasia. I am all in favor of letting people arrange for their own deaths on their own schedules whenever they feel moved to do so. My proposal can be seen, in fact, as a way of protecting the practice of voluntary active euthanasia from many of the pressures that now beset it.

I was proposing WBA as a way of removing from life’s burdens many of the opportunities that modern technology has vouchsafed us. Robert Nozick wrote of “coercive offers” and I am speaking of coercive opportunities: the myriad occasions and methods we now all have to engage in incessant self-monitoring: is my life good enough, am I healthy enough, have I lived too long? Am I still in the top ten or top one hundred on any scale, or has my ranking slipped (as professional, as grandparent, as object of desire, as entertainer, as friend, as neighbor)? We now live in a world in which quality control is possible on a day-to-day or even minute-to-minute basis across a wide spectrum of attributes, and many people seem to be bizarrely interested in tracking their trajectories on all these scales. We are in danger of becoming obsessive pulse-takers. Kurt Baier’s quip about the overexamined life not being anything to write home about is not just funny. It is, I think, deep and wise.

I am delighted to learn that my friend Stevan Harnad thinks “the world would be far, far better off with Dan Dennetts staying around as long as they are compos mentis” but I don’t want him, or society, or anybody else doing the assay to determine when I am no longer compos mentis enough to be welcome. And I don’t want to worry about it myself. I want that “decision” taken out of my hands, so that I can live my life full bore, without constant examination of the options. In place of his “individual, objective criteria” I want to put an arbitrary boundary, determined by nothing but blind chance.

Let me suggest a comparison. Mandatory retirement has now been abolished in universities in the United States, and as a result, many academics are hanging around longer than they really should, because nobody has the heart to tell them they are no longer pulling their weight. I expect that few would approve of a reform that instituted “individual, objective criteria” in an annual test which would leave aging professors filled with anxiety about whether or not they would pass this year’s 71-plus exam. Better to have an arbitrary rule. “My hands are tied,” the Dean would say, gratefully. “It’s the rule.”

Why, I asked in Consciousness Explained (1991, pp452-3), do we not simply discard the corpses of our friends with the trash when they die? You obviously can’t harm a corpse in any important way, and the person you loved no longer exists. The answer, clearly, is that as anticipating agents, we are constantly looking ahead as best we can, and we find that anticipating a future with one’s body treated with respect and decorum is less alarming, more comforting now, than imagining any sort of defilement or negligence. The belief environment in which we exist makes a big difference to our subjective well-being.

What I am suggesting in this essay is that our belief environment is now threatened by our growing capacity to prolong life but also to measure life, in hundreds of ways. (And whenever a capacity becomes widely exploited those who resist adopting it come under social pressure, not always subtle.) If you don’t want to have to shield your eyes from a hundred dials installed on your wrist letting you know that your health just went up from C+ to B- but your IQ dropped ten points in the last month and your worldwide popularity is now in steady decline, you should start thinking about the virtues of ignorance. There are some things we just don’t want to know, so we should consider taking steps now so that there won’t be any good reason to find these things out in the future.

Nick Humphrey suggests that a longer lame duck period—-not ten minutes but nine months of inverse gestation—-would be a likely improvement. Maybe he is right. I thought that the benefits of organizing farewell ceremonies and institutions would be soon provided by the recognition by all that when somebody has entered their period of final jeopardy (ouch), this is a time to get reflective and celebratory, and the sooner the better since you never know when somebody’s number will come up. But these and other options are worth exploring further. Nick and I have an old friend and colleague, Nina Murray, now 91, who speaks gallantly of leaving her home and going off to her “finishing school” where she now “circles the drain”. If we could all face death with her humor and clear-headedness, life itself would be better.

OPTING INTO NO- OPT-OUT APOPTOSIS

Dan thinks (now) that there would be more peace of mind in one’s last years (or maybe in one’s earlier ones too) if everyone were signed up for a no-opt-out 80-85 apoptosis policy.

When I was in my sophomoric teens, I contemplated having a vasectomy, “It is selfish and wrong for people to reproduce — to create, out of nothing, a potential for suffering, with the patient being someone other than themselves. (No potential for pleasure can compensate for this.)”

Friends said: Are you sure? What if, when you get older, you start to feel broody. You may rue this decision. It’s irreversible. You can’t opt out afterwards.

My (sophomoric) reply: “If I change my mind later on, it serves me right. What I think and feel now is right. If I change my mind at a later, then I’ll be wrong, then. I disavow my later avatar.”

But I never got ’round to having that vasectomy. And I did reach the broody age, when I was glad I had not, and declared my prior callow incarnation to have been the one that was wrong.

But I never got ’round to breeding either. (And now I’ve reached an age where I think I was right the first time.)

All by way of an analogy with Dan’s stance. What about freedom? And variations and variability in the life cycle? Is humankind to be pre-inscribed in a genetically engineered, no-opt-out 80-85 apoptosis policy? Without consultation? After a plebiscite? Does everyone feel that’s right for them?

Will Dan feel that way in the compos mentis and creative ’90s that I fervently wish upon him?

If Chris Hitchens had remained alive, compos mentis and creative till his ’90s, would he not have opted to keep struggling to live, think and write till the very last moment, as he did, mortally ill in his ’60s?

Stevan’s response is all very sensible and heartfelt but he never gets around to addressing the question of whether his vision of freedom could actually be counterproductive. All the people vegetating away in nursing homes probably share (or shared, when they were compos mentis) his vision of unshackled freedom. Odysseus showed us that if there are some things, some adventures, you want to have, you have to tie yourself to the mast so that you can avoid the negative after-effects of getting what you want.

Making plans that restrict your later actions is not, in general, a bad idea. Deciding not to continue my violin lessons some sixty years ago pretty well ensured that I was thereafter cut off from any futures involving playing violin in a string quartet, something I now faintly regret, but life is full of opportunity costs, and I bear that one gladly, since I think the life I have led without the violin is probably much, much happier than the life I would have led had I gritted my teeth and stuck with it. If my imagined apoptosis system existed and I availed myself of it, I might come to regret—even bitterly regret—having ensured my own demise by some random time shy of my 90th birthday, but it might still be true that the life I led, having committed myself to that course, was much better, all things considered, than any life I could have led without that commitment.

A question for those who just don’t see the point I’m trying to make: suppose today you got a credible offer of a two hundred year lifespan by taking a purple pill (and it’s free, if that matters). You have to take the pill now, and you don’t get any guarantees at all about what sort of life you’ll be living after, say, your 90th birthday. Do you take the pill? Think of how knowing something about your longevity will probably distort the rest of your life if you take the pill. Is it obvious that you should opt for the pill?

This conversation, while ending here, continues on Facebook. Join us there by logging on to your Facebook account and proceeding to our group: On the Human.