1. Introduction: The Battle of the Bulge

In trying to develop a theory of how consciousness arises in the brain, it is important to begin with an account of which kinds of brain events can be conscious. Once we know which brain events are conscious, we can investigate what distinguishes them from those that are not. Pretty much everyone agrees that some activities in the brain are never conscious. For example, it would be hard to find researches who think there can be conscious events in the cerebellum. Most researchers nowadays also deny that there can be conscious events in subcortical structures, though there is an occasional plea for the thalamus (Baars) or the reticular formation (Damasio). But what about the neocortex? Is any activity in that folded carapace a candidate for conscious experience? Does each cortical neuron vie for the conscious spotlight, like the contestants on a televised talent show? (Recall Dennett on “cerebral celebrity.”)

To make progress on this question, we can ascend from brain to mind, and ask which of our psychological states can be conscious. Answers to this question range from boney to bulgy. At one extreme, there are those who say consciousness is limited to sensations; in the case of vision, that would mean we consciously experience sensory features such as shapes, colors, and motion, but nothing else. This is called conservatism (Bayne), exclusivism (Siewert), or restrictivism (Prinz). On the other extreme, there are those who say that cognitive states, such as concepts and thoughts, can be consciously experienced, and that such experiences cannot be reduced to associated sensory qualities; there is “cognitive phenomenology.” This is called liberalism, inclusivism, or expansionism. If defenders of these bulgy theories are right, we might expect to find neural correlates of consciousness in the most advanced parts of our brain.

In this discussion, I will battle the bulge. I will sketch a restrictive theory of consciousness and then consider arguments for and against cognitive phenomenology.

2. The Locus of Consciousness

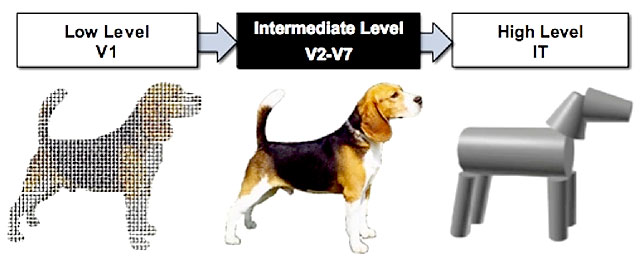

Not only do I think consciousness is restricted to the senses; I think it arises at a relatively early level of sensory processing. Consider vision. According to mainstream models in neuroscience, vision is hierarchically organized. Let’s consider where in that hierarchy consciousness arises.

Low-level vision, associated with processes in primary visual cortex (V1) registers very local features, such as small edges and bits of color. Intermediate-level vision is distributed across a range of brain areas with names like V2 through V7. Neural activations in these areas integrate local features into coherent wholes, but, at the same time they preserve the componential structure of the stimulus. The intermediate level represents shapes as presented from particular vantage points, separated from a background, and located at some position in the visual field. High-level vision abstracts away from these features, and generates representations that are invariant across a range of different viewing positions. Such invariant representations facilitate object recognition; a rose seen from different angles in different light causes the same high-level response, allowing us to recognize it as the same. Following Ray Jackendoff, I think consciousness arises at the intermediate level. We experience the world as a collection of bounded objects from a particular point of view, not as disconnected, edged, or viewpoint invariant abstractions.

To drive home this point, consider some facts about low- and high-level vision. The contents of low-level vision don’t seem to match the contents of experience. For example, when two distinct colors are rapidly flickered, we experience one fused color, but low-level vision treat the flickered colors as distinct; fusion occurs at the intermediate level (Jiang et al., 2007; see also Gur and Snodderly, 1997). Likewise, the low level seems oblivious to readily perceived contours, which are registered in intermediate areas (Schira et al. 2004). There is also evidence that the suppression of blink responses doesn’t arise until intermediate-level V3; V1 activity cannot explain why blinks go unperceived (Bristow et al., 2005). High-level vision does better than low-level vision on these features, but suffers from other problems when considered as a candidate for consciousness. Many high-level neurons are largely indifferent to size, position, and orientation. High-level neurons can also be indifferent to handedness, meaning they fire the same way when an object is facing to the right or the left. In addition, high-level neurons often represent complex features, so activity in a single neuron might correspond to a face, even though faces are highly structured objects, with clearly visible parts. It would seem that the neural correlates of visual consciousness cannot be so sparsely coded: just as we can focus in on different parts of a face, we should be able to selectively enhance activity in neurons corresponding to the parts of a face, rather than having a single neuron correspond to the whole.

Such considerations lead me to think that, in vision, the only cells that correspond to what we experience are those at the intermediate-level. I think this is true in other senses as well. For example, when we listen to a sentence, the words and phrases bind together as coherent wholes (unlike low-level hearing), and we retain specific information such as accent, pitch, gender, and volume (unlike high-level hearing). Across the senses, the intermediate-level is the only level at which perception is conscious.

I now want to argue that all conscious experience can be fully explained by appeal to perceptual states at the intermediate-level, including conscious states that seem to be cognitive in nature. That makes me a restrictivist.

3. Arguments for Cognitive Qualia

Expansionists say we can be conscious of concepts and thoughts, and that such experiences outstrip anything going on at the intermediate-level of perception. Here I will review my favorite expansionist arguments. I cannot do justice to these arguments here, but they will serve to illustrate some of the response strategies available to restrictivists.

Tim Bayne (2009) defends expansionism by appeal to a neurological disorder called associative visual agnosia. Such agnosics cannot recognize objects, but they seem to see them. When presented with an object, they can accurately describe or even draw its shape, but they can’t say what it is. Bayne thinks their experiences are incomplete. He thinks knowing the identity of an object changes our experience of it. This is intuitively plausible. Consider the picture below. You may not be able to make it out at first, but when you do (hints below), it will change phenomenologically.

Does the phenomenological change here require cognitive phenomenology? I think not. Instead, we can suppose that our top-down knowledge of the meaning changes how we parse the image. When we decipher the picture, we imaginatively impose a new orientation (we rotate 90 degrees to the left); we segment figure and ground (the lower black bar becomes background); and we generate emotions (social delight) and verbal labels (the name “Tim”), which we experience consciously along with the image; these are just further sensory states—bodily feelings in the case of emotions, and auditory images in the case of words. I think features of this kind can also explain what is missing in agnosia. Without meaning, images can be hard to parse, and associated images and behaviors do not come to mind.

Another argument comes from Charles Siewert (1998; forthcoming). He focuses on our experience of language. Sometimes, when hearing sentences, we undergo a change in phenomenology, and that change occurs as a result of a change in our cognitive interpretation of the meanings of the words. For example, if you hear an obscure sentence without following it, and then re-read with full comprehension, your experience seems to change. Likewise, if you change your interpretation of an ambiguous word. Phenomenology also changes when we repeat a word until it becomes meaningless, or when we learn the meaning of a word in a foreign language. In all these cases, we experience the same words across two different conditions, but our experience shifts, suggesting that assignment of meaning is adding something above and beyond the sound of the words.

The intuitions here are compelling. Clearly the very same sentence can give rise to different experiences depending on how it is understood. But there are many sensory changes that take place as a result of sentence comprehension. First, we form sensory imagery. If I tell you that ng’ombe means cow in Swahili, you will undoubtedly form a visual image of how cows appear. Repeating “cow” over and over will cause the cow image to fade and attention to focus on the sound of that peculiar word. Second, comprehension effects parsing. When we come to comprehend a sentence, intonation and phrase bindings may alter in our verbal imagery. If I tell you that habari gani is a question, you will repeat it with a rising pitch on the second word. Third, comprehension entails knowing how to go on in a conversation; if I ask, “Habari gani?” you might be left in a silent stupor, but, if I say “How are things going?” your mind will fill with appropriate verbal replies. Fourth, meaning effect emotions. Incomprehension can engender feelings of confusion, frustration, or curiosity. Comprehension can evoke emotions that depend on meaning. To take a Siewart example, if I say, “I’m very hot,” you might feel annoyed at my vanity or concerned about my thermal state. Different actions may follow and produce bodily sensations; an eye-roll of exasperation or a hospitable dash to the air conditioner.

The third argument I will consider comes from David Pitt (2004). He begins with the observation that we often know what we are thinking, and we can distinguish one thought from another. This knowledge seems to be immediate, not inferential, which suggests we know what we are thinking by directly experiencing the cognitive phenomenology of our thoughts.

The most obvious reply is that knowledge of what we are thinking is based on verbal imagery. I know that I am thinking, “Expansionism lacks decisive support,” by experiencing those very words in my mind’s ear. Pitt counters that knowledge of what we are thinking cannot consist in verbal imagery, because comprehension is immediate, and verbal images are only indirectly related to thoughts. Just as we can hear a sentence without knowing its meaning, we could hear words in the mind’s ear without knowing what they mean. But, when we become aware of our thoughts, we are immediately aware of their meaning.

I think this is a kind of illusion. We erroneously believe that we are directly aware of the contents of our thoughts when we hear sentences in the mind’s ear. This belief stems from two things. First, we often use verbal imagery as a vehicle for thinking; for example, we might work out technical philosophical problems using language. Second, when contemplating a word that we understand, we can effortlessly call up related words or imagery, which gives us the impression that we have a direct apprehension of the meaning of that word. Our fluency makes us mistake awareness of a word for awareness of what it represents. This illusion goes away when we hear words in a foreign tongue or sentences we cannot parse. The claim that we grasp the content of our words and not just the words themselves cannot be maintained without an account of what that content consists in. Many philosophers believe that content is not in the head, but in the world (the meaning of a thought is the fact to which it refers), in which case content could not be directly grasped. Pitt might suggest that we grasp words in a language of thought, which are intrinsically meaningful, but the claim that we have a language of thought, beyond the languages we speak, is hugely controversial, and even its primary defenders (e.g., Jerry Fodor) have never suppose that the language of thought is conscious—otherwise he could convince people that it exists by introspection.

Putting these points together, I think restrictivsts should admit that thinking has an impact on phenomenology, but that impact can be captured by appeal to sensory imagery including images of words, emotions, and visual images of what our thoughts represent. Expansionists must find a case where cognition has an impact on experience, without causing a concomitant change in our sensory states. That’s a tall order.

4. Arguments Against Cognitive Qualia

At this point the dispute between restrictivists and expansionists often collapses into a clash on introspective intuitions. Restrictivists give their strategies for explaining alleged cases of cognitive phenomenology, and expansionists object that these strategies do not do justice to what their experiences are like. By way of conclusion, I will try to break this stalemate by sketching five reasons for thinking restrictivism is preferable even if introspection does not settle the debate.

The first argument was already intimated above. To make a convincing case for cognitive phenomenology, expansionists should find a case where the only difference between two phenomenologically distinct cases is a cognitive difference. But so far, no clear, uncontroversial case has been identified. This is a striking failure given the ease with which we can find clear cases of sensory qualities. If every phenomenal difference has a plausible candidate for an attendant sensory difference, the simplest theory would say that sensory qualities, which every one agrees to exist, exhaust phenomenology.

The second argument points to the fact that alleged cognitive qualities differ profoundly from sensory qualities in that the latter can be isolated in imagination. If I see an ultramarine sky, I can focus on the nature of that hue and imagine it filling my entire field with no other phenomenology. In contrast, it seems impossible to isolate our thoughts. For example, it doesn’t seem possible to think about the fact that the economy is in decline without any words or other sensory imagery. If other qualia can be isolated, why not cognitive qualia?

Third, it is nearly axiomatic in psychology that we have poor access to cognitive processes. For example, when comparing three identical objects, people prefer the one on the right but they don’t realize it (Wilson and Nisbett, 1978). All we experience consciously is the outcome, a hedonic preference for the rightmost object, together perhaps with some confabulated justifications of the choice, which may be experienced through inner speech. Given the fact that cognitive processes are characteristically inaccessible, the claim that we can be conscious of our thoughts is perplexing. If so, we don’t have access to all the biases that influence how we think. The only processes we ever seem to experience consciously are those that we have translated, with great distortion, into verbal narratives.

A fourth argument follows on this one. The incessant use of inner speech is puzzling if we have conscious access to our thoughts. Why bother putting all this into words when thinking to ourselves without any plans for communication? I suspect that the language is a major boon precisely because it can compensate for the fact that thinking is unconscious. It converts cognition into sensory imagery, and allows us to take the reins.

Finally, expansionism seems to dash hopes for a unified theory of consciousness. If only one kind of mental state can be conscious—intermediate-level perceptions—then there is hope of finding a single mechanism of consciousness. Indeed, I think that mechanism has been identified; there is evidence for the conclusion that perception is conscious when and only when we attend (Mack and Rock, 1998; Prinz, forthcoming). But there is little reason to think a single mechanism could explain how both perception and thought can be conscious, if cognitive phenomenology is not reducible to perception. This is especially clear if the mechanism is attention. There is no empirical evidence for the view that we can attend to our thoughts. There are no clear cognitive analogues of pop-out, cuing, resolution enhancement, fading, multi-object monitoring, or inhibition of return. Thoughts can direct attention, but we can’t attend to them. Or rather, thoughts become objects of attention only when they are converted into images, words, and emotions. Expansionists might say that thought and sensations attain consciousness in different ways, but, if so, why think that the term “consciousness” has the same meaning when talking about thoughts, if it does not refer to the same mechanism? Disunity threatens to make expansionism look like an unwitting pun.

For some people it’s introspectively obvious that we have cognitive phenomenology; for me, I am somewhat embarrassed to confess, it’s obvious that we don’t. Perhaps introspection cannot resolve this debate (cf. Schwitzgebel, forthcoming). Even so, I hope these concluding arguments might collectively tip the balance towards restrictivism.

References

Baars, B. J. (1988). A cognitive theory of consciousness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bayne, T. (2009). Perception and the reach of phenomenal consciousness. Philosophical Quarterly, 59, 385-404.

Bristow, D., John-Dylan Haynes, J-D., Sylvester, R., Frith, C.D., & Rees, G. (2005). Blinking suppresses the neural response to unchanging retinal stimulation. Current Biology, 15, R554-R556.

Damasio, A. R. (1999) The Feeling of What Happens: Body and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness. New York, NY: Harcourt Brace & Company.

Gur, M. & Snodderly, D.M. (1997). A dissociation between brain activity and perception: Chromatically opponent cortical neurons signal chromatic flicker that is not perceived. Vision Research, 37, 377–382.

Jackendoff, R. (1987). Consciousness and the computational mind. Cambridge, MAL MIT Press.

Jiang, Y, Zhou, K. & He, S. (2007) Human visual cortex responds to invisible chromatic flicker. Nature Neuroscience, 10, 657-662.

Mack, A., & Rock, I. (1998). Inattentional blindness. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Pitt, D. (2004). The phenomenology of cognition, or, what is it like to think that P? Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 69, 1-36.

Prinz, J. J. (forthcoming). The conscious brain. New York: Oxford University Press.

Schira, M., Fahle, M., Donner, T., Kraft, A., & Brandt, S. (2004). Differential contribution of early visual areas to the perceptual process of contour processing. Journal of Neurophysiology, 91, 1716–1721.

Schwitzgebel, E. (forthcoming). Perplexities of consciousness. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Siewert, C. P. (1998). The significance of consciousness. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Siewert, C. P. (forthcoming). Phenomenal thought. In T. Bayne and M. Montague, eds., Cognitive Phenomenology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

I agree with Jesse Prinz that phenomenal consciousness is constituted by representations at what he calls “the intermediate level”. Phenomenal consciousness is non-conceptual (albeit involving representations of bounded objects), and the application of concepts in experience, while it can have a causal impact on phenomenal consciousness, fails to play any constitutive role in our experience. (In agreeing with Jesse on this, I am going back on something I defended in my book, Phenomenal Consciousness [Cambridge, 2000]. My mind was changed by an ex-graduate student, Bénédicte Veillet, with whom I have a jointly-authored paper attacking cognitive phenomenology. See http://www.philosophy.umd.edu/Faculty/pcarruthers/Articles-c.htm.

It is important to distinguish between access consciousness and phenomenal consciousness in this context, however. For concepts and propositions can be access conscious. When we listen to others speak (or to our own inner speech) we hear not just sounds but also meaning. Likewise we see bounded objects as table, chairs, people, or whatever. And indeed, many cognitive theories of perception suggest that high-level conceptual information is bound into the nonconceptual (phenomenally conscious) content produced at the intermediate level, and is globally broadcast along with the latter (thereby becoming access conscious).

Like Prinz, I also believe that this is the only way in which concepts and thoughts can become access conscious. There is no such thing as direct knowledge of our own thoughts and thought processes independently of any sensory presentation. We only know what we are judging or deciding by accessing our own inner speech or other imagery (or our own overt behavior) and interpreting accordingly. But I don’t think this because I am an empiricist about concepts, or because I endorse sensorimotor accounts of cognition. On the contrary, I believe that abstract, amodal, concepts are frequently tokened in the mind, and many unconscious inferential processes take place involving them. But the only way in which concepts can become access conscious is by being bound into sensory information and entertained in a sensory-based global workspace or working memory system. (These views are defended at length in my forthcoming book, The Opacity of Mind: An integrative theory of self-knowledge, which will be published by Oxford in 2011.)

We’re very much fellow travellers. I should remark for other readers that Peter has done more than any other active philosopher to advance (with powerful arguments) the view that we become aware of thoughts through inner speech. The import of this fact has not been adequately appreciated. I’ve come to think that language serves as a kind of rationalist overlay on an empiricist mind. Of course, Peter would deny the empiricist mind part (at least the old-fashioned version of it, according to which thought is couched in modality-specific codes). My confidence in restrictivism increases knowing the excellent work that Peter has done to defend the view without recourse to an imagistic theory of thought.

In previous professional incarnations I was a perception psychologist and then an emotion theorist. In each case I was captivated by a paradigmatic example of consciousness without sensation. I am curious, therefore, to hear how Prinz would deal with these examples, since on its face that sort of thing is contrary to his thesis.

In perception I belonged to the Gibsonian school — folks who accepted psychologist J.J. Gibson’s idea that (in the case of vision) “the information is in the light.” The point was that literal seeing was at base perceptual rather than sensory, or in other words, and contrary to the then-prevailing view, we see things “directly” rather than inferring their existence and qualities from sensations. What enables this to be so, according to Gibson, is that we are active observers; we literally move around when mining the stimulus surround. Gibson would forever note that visual illusions are most likely to arise when we are held still in a laboratory, such that we become passive receptors of sensations or impoverished information.

The example that I came up with to illustrate Gibson’s theory was seeing the wind. To me it was, and remains, obvious that the wind is visible. The sensation-based contingent insisted that only the tree and its moving branches etc. were visible, from which we inferred that the air was moving. I took the definitive refutation of that position to be my 5-year-old stepson Sean’s peering out the window one day and exclaiming, “Man, look at that wind!” He wasn’t inferring anything. He was just seeing it.

Now, what would Prinz say? I suppose he would point out that: no sensation of moving branches, then no visual perception of wind. But are the moving branches really “components” of the wind? It seems to me that the wind itself has no color or shape, and yet it is entirely visible — just as visible as the moving branches, in fact. I am not claiming this necessarily as any kind of refutation of restrictivism. For one thing I am dealing with phenomenology, while Prinz was willing to concede a stalemate in that realm. Mainly I seek clarification or further articulation of his thesis.

Meanwhile in emotion I was allied with the cognitivists — those who denied that emotions are mere sensations or “tickles” (a Rylean word) but consist of judgments or beliefs. (Bob Solomon was the pioneer here. My own wrinkle was to add desire to the mix.) An example I took to make the point was the kind of anguish one feels in one’s chest, which might lead one even to “beat” it. What struck me one day while in such a state myself was that the actual bodily sensation was hardly noticeable. In fact I could not be sure there was any bodily sensation at all, although a localization (of the anguish) was somehow felt. In any case whatever sensation there might have been could hardly account for the intensity of the conscious anguish.

Upon reflection the cognitive/conative theory then made perfect sense: For I was at that time deeply yearning for (desiring) something and believed that I could never have it. What more was needed to “feel” lousy? Why would there also need to be some bodily sensation in my chest? And as I say, I’m not sure there even was a sensation, but if there was it certainly did not correspond to the anguish I was acutely aware of. So how would Prinz deal with that?

By the way, if Prinz seizes upon the felt location as the bodily basis for the conscious “mental” emotion, I would point out that I commonly sense that my thoughts are in my head. (A modern-day Cartesian, like Jerome Shaffer, would argue that a mental phenomenon cannot occupy a location in physical space.) So by winning the battle of emotion in that way, Prinz could lose the war of restrictivism.

Marvelous questions, Joel. On the wind (that’s a great example), I’m inclined to say that our experiences of the blowing trees is simultaneously an experience of the wind. Our perceptual states get meaning from what they detect. An experience of blowing trees detects (i.e., is reliably caused by) wind, so that experience represents the wind. I think this allows me to be Gibsonian about the wind, while still saying that the phenomenology is tree-like. A similar story might go for seeing persons. If I see Joel, my eyes pick up light reflecting on his skin from one vantage-point. Joel is not his skin. But since this experience reliably detects Joel, it is a representation of Joel. So, in this sense, we experience things that go beyond appearances.

On emotions, I’m an old-fashioned Jamesian. So I think anguish is mostly about the ache in the chest. But I also think emotions come along with changes in information processing. Attention is drawn to the objects of our emotions, and we may form obsessive thoughts, which can be experienced though imagery or inner speech. There is wonderful research suggesting that emotions influence perception as well. So the global impact of emotions may color experience profoundly, even if emotions themselves are just felt changes in the body. Those global effects can make an emotion feel consuming or intense even if the bodily symptoms are minor.

I share Jesse’s vision that all consciousness is perceptual. I disagree with him about what’s the best way to convince the rest of the world that this is the case.

1. What’s the question?

There is an ambiguity in the way Jesse raises the question. It seems to me that there are two questions here:

(a) What is the reach of perceptual phenomenology? Suppose that I am looking at an apple. Some, but not all, of its properties are part of our perceptual phenomenology? Shape and color are safe candidates, but how about being an apple? How about being edible?

(b) Do we need to postulate non-perceptual phenomenology in addition to perceptual phenomenology (however rich or poor perceptual phenomenology may be)?

Depending on the way we answer (a), the answers to (b) will also look different. If we endorse a minimalist conception of perceptual phenomenology (where only shape and color are part of our perceptual phenomenology), positing a non-perceptual phenomenology may look like a good idea. If we go for a richer conception of perceptual phenomenology, the idea of cognitive phenomenology may look less warranted.

Jesse chooses the most difficult task: he endorses a minimalist conception of perceptual phenomenology while arguing against cognitive phenomenology. But this is not the only, and not the most plausible, way of defending the view that all consciousness is perceptual. I assume that Jesse really cares about (b): about whether consciousness outstrips perception. And we may need to use a less minimalist conception of perceptual phenomenology than his in order to make this claim plausible.

2. Jesse’s five arguments

Jesse gives us five arguments in favor of the view that consciousness fails to outstrip perception. I don’t think any of them will move his opponents.

Three of the arguments appeal to our intuitions in one way or another. The first one is about (the lack of) contrast class arguments, where the only difference between two phenomenally distinct cases is a cognitive difference. The second argument is based on the intuition that one can isolate perceptual but not cognitive phenomenology. And the fourth argument takes it for granted that inner speech is rife.

The expansionist will undoubtedly deny each and every one of these assumptions. As long as the evidence in favor of Jesse’s restrictivism is based on intuitions, it is very easy to just deny these intuitions. If I say that two scenarios are not phenomenally distinct, and you say they are, what could possibly decide between my claims and yours?

The third argument seems to suggest that as our access to our cognitive processes is unreliable, we are unlikely to be conscious of them. I’m not sure how this is supposed to work. Why couldn’t we have conscious but unreliable access to our cognitive states? Consciousness can, and does very often, misrepresent. Why couldn’t it misrepresent (or even systematically misrepresent) in the case of cognitive phenomenology?

The fifth argument is an inference to the best (or, rather, better) explanation: if there are only one kind of phenomenology (i.e., perceptual phenomenology), we can explain it more easily. If there are two kinds (perceptual and cognitive phenomenology), this will be more difficult. Thus, we should go for the former claim. An analogy that should make us suspicious of this strategy: it would be nice to give one monolithic explanation for all respiratory infections, but it happens to be the case that some are caused by viruses and some by bacteria. Having a monolithic theory of respiratory infections would be unlikely to help us to get better.

3. Where to turn?

How then can we settle questions about cognitive phenomenology? It seems unlikely that any appeal to introspection or intuitions will help. But then what will?

The general strategy of those who don’t like expansionism is to appeal to (something like) mental imagery. The phenomenal character of thoughts is in fact (quasi-)perceptual because thoughts are (necessarily?) accompanied (constituted?) by mental (visual, auditory, etc) imagery. Jesse uses various versions of this strategy both here and in his 2007 paper.

The appeal of this strategy depends heavily on what properties are attributed in these thoughts. If these properties are obviously part of our perceptual phenomenology, as in the case of the thought that my first car was grey, it is easier to argue that the phenomenal character of this thought piggybacks on the phenomenal character of the visual imagery of the grey car. If the attributed property is less obviously perceptual, as in the case of the thought that my first car was fuel-efficient, this would be more difficult.

And this is where (a) becomes relevant. If we can show that perceptual phenomenology is very rich, we have a better chance of running the standard argument in favor of the view that all consciousness is perceptual. If a property is part of our perceptual phenomenology, then it is plausible to say that when a thought attributes this property, it inherits in some way the property’s perceptual phenomenology. If we can show that a wide range of properties are part of our perceptual phenomenology, and do so without relying on intuitions about phenomenology, we get a step closer to defeating potential examples of cognitive phenomenology.

Although Jesse and I share a passion for minimalism in 1960s European modernist cinema, when it comes to perceptual phenomenology, minimalism may not be the best bet for those who want to argue that all consciousness is perceptual. In order to “battle the bulge”, we need to buff up our perceptual phenomenology.

Hugely helpful. I think the distinction between questions (a) and (b) can do much to sharpen debate on this topic. In some sense I’m a minimalist, as Bence suggests, but I also think that the shapes and colors of experience can represent other properties (like the wind, in Joel’s example), so maybe I’m a kind of maxi-minimalist. Lycan has the useful view that phenomenal states have layered content. We might represent a tiger by representing its striped surface and contour. Perhaps the intuition that phenomenology outstrips perception comes from the fact that the colors and shapes in experience register the presence of objects and properties that outstrip the sensory. But, for me, they always do so by means of sensory features.

On the arguments, I am afraid Bence is right that the opposition won’t be convinced. Let me clarify, though, the parsimony argument. With respiratory infections, there is a common denominator. Even if the causes are different, the effects on the respiratory system may be the same. Likewise, different kinds of consciousness (say visual and auditory) share something in common: they both have qualitative character. They originate from different sources, but the common effects need to be explained. I think the phenomenology of thought must have an explanation that explains why it is phenomenological–i.e., why it feels like something, just as vision and sound feel like something. We need a uniform theory of phenomenality, even if there are differences in the qualities that have phenomenality.

Very interesting. it is a little-known fact that Sigmund Freud was an early advocate of the restrictivist thesis. Freud argued that all cognitive processes occur unconsciously, and that some are represented in consciousness by activating motor speech impulses (“verbal residues”), which, although truncated before producing muscular movements, produce afferent feedback which we experience as the inner monologue of conscious thought (for the details see my 1999 book “Freud’s Philosophy of the Unconscious”).

Great lead. I hadn’t appreciated this. I suspect that restrictivism was once a more common view, though debates about it ultimately undermined introspective psychology. Kulpe argued that there are introspectable imageless thoughts, and Titchener could only reply that he couldn’t find any when he introspected. Without resolution, the whole movement was undermined. Freud is a step forward because his arguments for thoughts being unconscious do not rely on introspection.

From 1895 onwards, Freud rejected the neo-Cartesian package of dualism and introspection that dominated psychology. He denied that, strictly speaking, cognitive processes are introspectable.

Jesse Prinz thinks that consciousness doesn’t outstrip sensation. He’s put the case against the opposing view—the view that there is such a thing as “cognitive phenomenology” or as I like to call it “cognitive experience”—in a very clear, straight and helpful way. I disagree with him completely!

“For some people,” Jesse says, “it’s introspectively obvious that we have cognitive phenomenology; for me, I am somewhat embarrassed to confess, it’s obvious that we don’t.” I’m one of those to whom it’s obvious that we do. So, next time we meet, he and I will stare at each other incredulously! That encounter, to which I greatly look forward, will, for me—as I remember why he and I disagree—be a conscious experience whose phenomenological character will far outstrip mere sensation and feeling!

One way to make the point is to note that one often reads or hears words or thinks thoughts that are extraordinarily interesting. They’re experienced as interesting. Suppose that you’re interested in what you’re reading now (it’s not impossible). Clearly your being interested must be a response to something in the content of your experience. So what is it in the content of your experience that it’s a response to? Why are you continuing to read (if indeed you are)? What is it about the character of your experience that’s making you continue? Is it merely the sensory content of the visual or auditory goings on? Obviously not. It’s the cognitive-experiential content of your experience as you now consciously and more or less comprehendingly register the cognitive content of the sentences.

If you want to try to give anything like a full account of the experiential or lived character of our experience in merely sense/feeling terms, you’re going to have to be able to explain, in those terms alone, how the experience of looking at a piece of paper with a few marks on it, or of hearing three small sounds, can make someone collapse in a dead faint. Look at a class of motionless children listening raptly to a story. You have to give a full explanation of the exceptional physiological condition into which the story has put them by reference to nothing more than the auditory experience of the spoken words.

“Not so fast,” says Jesse, or someone sympathetic to his general view. “Such people do indeed experience powerful feelings, and this explains their behaviour. And they experience these feelings because the sounds or marks affect them, and because they affect them as things that have a certain meaning, a meaning that it is correct to say that they understand. All this is true. But—nevertheless—what we call their understanding is wholly a matter of their non-conscious processing of the sounds or marks. Understanding, considered specifically as such, has no experiential aspect. All we actually experience, strictly speaking, in these cases, are sounds or marks, and then, as a result of the non-conscious processing, we undergo various purely sense/feeling episodes—shock or excitement, say, or ‘epistemic emotions’ such as interest and curiosity. Experience, experience strictly speaking, experience as such, remains wholly a matter of sense/feeling experience.”

Let me try again. Consider this argument.

Premiss 1 (1) if cognitive experience didn’t exist, life would be entirely boring.

Premiss 2 (2) life is intricately and complexly interesting and various.

Conclusion (3) cognitive experience exists.

On the no-cognitive-experience view, it seems, life, life-experience, is utterly without real interest. It may contain terrific basic sensual sense/feeling pleasures, and many other sense/feeling pleasures, including such sense/feeling pleasures or “epistemic emotions” as the interestedness-feeling. But experience itself, strictly considered, neither has nor can have any content of a sort that could make it interesting—even if it’s constant sense/feeling heaven (which is not my experience). On the no-cognitive-experience view, we sometimes have the interestedness-feeling, but this is wholly a matter of sense/feeling experience, and we’re never interested because we consciously grasp or entertain the meaning of something. Why is this? Because we never consciously grasp or entertain the meaning of anything, on this view! Instead we (1) non-consciously register some content, in a way that is (on the no-cognitive-experience view, and as far as phenomenological goings on are concerned) no different from the way in which machines can be said register some content. This then causes (2) a certain sort of sense/feeling experience, a certain quantum of interestedness-feeling, say—experience which involves no experience of the specific content of the registered content.

Note that this interestedness-feeling is necessarily generic in character. Consider thinking three thoughts p, q, and r that are equally interesting to you. They’re fascinating to you. These thoughts may be about very different things, but it’s their content that differentiates them, and this isn’t something that’s consciously experienced in any way, on the no-cognitive-experience view. We can and often do experience quasi-acoustic mental word-images as we think thoughts, but we also often think thoughts too fast for this to happen (in such cases the word-images come when we mentally repeat the thoughts more slowly, after having already entertained or experienced their content). And, whether or not we have any quasi-acoustic mental word-images in the case of thinking p, q, and r, it may be that the only other thing that’s experienced, so far as these thoughts are concerned, is the interestedness feeling. But we’ve supposed that p, q, and r all give rise to exactly the same amount of interestedness-feeling. So the thinkings of these thoughts are either all experientially the same, in the moment of their occurrence, or they differ only in meaningless differences of quasi-acoustic word-images.

One can re-express this by saying that the interestedness-feeling must be “monotonic,” on the no-cognitive-experience view. It must be monotonic in the sense that it is, as a specific type of sense/feeling phenomenon, only ever a matter of more or less. On the no-cognitive-experience view, variety in experience comes only from variety in colours, sounds, and so on, together with variation in the degree of intensity of other feelings such as the interestedness-feeling or curiosity-feeling. This is, certainly, a lot of variety, a great deal of richness of experience. But these riches are desperate poverty when placed next to the astonishing variety that I and 99.9999999 per cent of humanity know that experience can have and does have on account of the fact that it involves experience of different thoughts and ideas.

There is I think something astonishing in the fact that the existence of cognitive experience is a matter of dispute. Somehow we’ve managed to create a form or climate of theoretical reflection in which this evident, all-pervasive fact can seem hidden from us. When we think theoretically about the overall or global character that our conscious awareness has as we hear someone speak, or when we speak alertly and meaningfully ourselves, or consciously think something, it seems that the fact that we are consciously apprehending meaning, having cognitive experience in addition to any sense/feeling experience, can somehow fail to be apparent to us. It’s as if the abstractness and intangibility and speed of cognitive experience makes it hard to grasp, even though it’s a massive part of experience. One has a genuine sense of puzzlement about what exactly this “cognitive experience” is meant to be. I’ve certainly experienced this puzzlement.

Nevertheless there is I think a simple and infallible way of encountering the phenomenon of cognitive experience, in such a way as to see that it exists, even when thinking about the matter theoretically. Wait until the next time—perhaps a quiet time—when someone asks you “What you are thinking about?” What will happen? You will have to think back a little in order to reply. What will this be like? Here’s my prediction: it’s not merely that the existence of cognitive experience or cognitive phenomenology will be plain to you as part of what you remember, when you review your immediately past course of experience. It’s also that your remembering, considered simply as what is going on in the present moment, will, with the content that it has, itself be an evident instance of the phenomenon of cognitive experience. It will be an instance of cognitive experience that is particularly vivid, given the way it’s framed by the particular circumstance of your having being asked—out of the blue—what you were thinking about.

Foolishly, thinking about my favorite arguments for the phenomenology of thinking, I forgot a favorite. Galen’s interesting argument from interestingness. Galen is a long-time support of cognitive phenomenology, and one of the most inventive. His basic move here is that when we find ourselves interested in a thought, it must be the phenomenology of the thought that captivates our interest. I find the phenomenology of interest fascinating, and have thought about it most in the aesthetic context. I think interest (or a specific species: wonder) is crucial for positive aesthetic appraisal. When we look at a good artwork, it captures our interest, and, presumably, it is the experience of the work that does so. Likewise, one might suppose, for interesting thoughts. Here I demur. I think thoughts can capture our interest unconsciously. In many cases, what we find interesting is the unconscious representation of a thought’s content. Indeed, I think we often find ourselves interested without being consciously aware of what captured our interest. A painting or a story or an article might have us gripped, but we can’t quite place why. Interest can be experienced as a focused state with high arousal. We can even have interest without any content, as when I say, “What follows will interest you.” You prick up your ears before you’ve heard another word. Free floating interest.

Galen counters: surely two different thoughts that are both interesting feel interesting in different ways. Consider two thoughts expressed by, “The rat entered the factory.” This could mean that a scab worker entered, violating a union strike, or that a rodent entered. Both would be interesting. But clearly they are interesting in different ways and those differences are phenomenological. I concur. But there are two features of my story that can help explain this. First, we can form different images of these sentences, and second, once our interest is captures, a sequence of thoughts and images follow, and the sequence will differ in the two cases. So there is a lot going on phenomenologically.

The hardest cases for me are very abstract thoughts. One might be interested in a math problem, for instance, even when there is no associated imagery. But the interest may work it’s way into phenomenology by the mental activity of thinking about the problem. Trying solutions. Experiencing puzzlement. Filtering out background noise. Rejoicing in each minor breakthrough. For me, this experience is nothing but a sequence of words an emotions, so, unless mathematical meaning is symbolic, we are not experiencing the actual objects of interest. But there is a phenomenology of finding the math problem interesting. And for that reason, our level of interest is phenomenally manifest. But why think it is also manifest what has captured our interest? Two cases: either we can report what’s interesting, in which case the content seems phenomenally available because of the available phenomenology of report (a kind of illusion of cognitive phenomenology); or we have no such access. In the latter case, which is quite common, we report that we are interested without knowing what in particular made us so, and that, I submit, indicates that the actual cause of often falls outside of the phenomenal spotlight.

Of course, this can happen with art as well. We may be drawn to a picture because of its composition while thinking, incorrectly, that it is the form or the content that attracts us.

My warm thanks to Galen for this.

I am new to the question Prinz tries definitively to answer here, but reading through his original post and its (very interesting) replies nudges me toward a bulgy view of my own consciousness. Can’t speak for the rest of you, of course, but in my own case I am struck by the sensory poverty of a phrase like “cognitive experience.” Yes, it’s got that nice, crunchy “x” in the middle, and if I pause I can conjure a juicy image of exposed brain matter, but these are very nearly immaterial to the cognitive impression the phrase makes on me. I think one could as easily say that its sensory associations and accoutrements “merely” frame or inflect its abstract content as the other way around.

In considering the relative salience of sensory and abstract content to conscious thought (though the question seems to be whether “abstract content” is an oxymoron), the phenomenon of the cliché seems potentially useful. A few weeks ago, I had told a friend I thought a song would be “right in your wheelhouse.” (We’re karaoke buddies.) She’d never heard the expression, and I could tell her only that it meant she’d sing it well. We were with other friends this weekend, and she asked whether anyone knew what a wheelhouse “really” was. I had no image for it, she was imagining a kind of millwheel and grain being pulverized, but someone else explained that it came from baseball: the wheelhouse is your own personal strike zone. Thus my friend and I made a reverse journey up the path of cliché, from abstraction to sensory richness. My point is that language and other cognitive technologies tend to proceed (for better or worse) in the denuding direction, that our facility with them often involves a shedding of sensory association.

While it may be true that we cannot represent ideas to ourselves perfectly free from sensory anchors, isn’t the opposite true as well? The vagaries of attention suggest that meaning must permeate sensation for conscious perception to occur — is the dichotomy here a false one?

I love the wheelhouse example. That one is also new to me, so I could be a fellow traveller in the road from abstraction to imagery. No doubt the word primes wheels and houses, which are highly imageable, but I would concede that the phrase gets its initial feel from the original gloss, “You’d sing it well,” and not the free associations (I pictured a wooden shack for keeping horse-drawn carts). But once we get the meaning (“You’d sing it well”), I think there is a story about sensory phenomenology. The meaning draws attention to the sound qualities of the song and the vocal qualities of the singer. One finds oneself imagining what she would sound like singing that sound, and the claim seems apt if imagination delivers up a good rendition. If we looked at this with fMRI, my guess is we’d see a lot of auditory cortex coming online.

Of course, my intuitions on the case can’t prove there is no cognitive picture in the sensory frame, but I am always struck by how hard it is to find cases where nothing sensory comes for the ride. Great case to think about.

Prinz confesses to an ulterior motive: that since his own theory of consciousness, the “AIR” theory (acronym for “attended intermediate-level representations”) applies only to sensory states, cognitive phenomenology would require a different theory entirely. That motive is fine of course, but we should ask what a neutral party might think on the issue.

Prinz maintains (as did Eric Lormand in “Nonphenomenal Consciousness,” Noûs 30 (1996): 242-61) that all alleged cases of cognitive phenomenology involve sensory imagery and are conscious solely in virtue of that. Thus, anent Siewert’s example of understanding a sentence upon hearing it, Prinz insists that we do that only by forming sensory imagery of one kind or another; and to Pitt’s example of knowing immediately what we are thinking, he replies that the knowledge is not immediate, but is mediated by mental verbalizing, and the seeming immediacy is an illusion.

Of course, sometimes such experiences do involve sensory imagery. But what is supposed to convince us that every such case must involve such imagery? Prinz writes, “Expansionists must find a case where cognition has an impact on experience, without causing a concomitant change in our sensory states. That’s a tall order.” But expansionists have put forward any number of apparent such cases. Besides the two just cited:

Alvin Goldman cites the tip-of-the-tongue phenomenon. “When one tries to say something but cannot think of the word, one is phenomenologically aware of having requisite conceptual structure, that is, of having a determinate thought-content one seeks to articulate…. Entertaining the conceptual unit has a phenomenology, just not a sensory phenomenology” (“The Psychology of Folk Psychology,” Behavioral and Brain Sciences 16 (1993): 15-28). Secondly, he points out, “Someone who had never experienced certain propositional attitudes, for example, doubt or disappointment, would learn new things on first undergoing these experiences”; viz., the subject would learn what it is like to undergo them, from which it follows that there is something it’s like. Third, subjects introspect differences in strength or intensity between their propositional attitudes—strength of desire, firmness of intention, happiness with this or that state of affairs, confidence in judgment.

In addition to his sentence-understanding example, Siewert cites “sudden wordless thoughts” of the sort that sometimes occur to us, where there is “an abrupt shift in the direction of thought” (I remember an appointment, I am relieved to find my car keys in my other pocket, I am struck by the structural resemblance of my current situation to a previous one). These thoughts can be formulated in words, but only after the fact, and they are unaccompanied by imagery. Yet they have their respective experiential qualities. (Of course, many other sudden thoughts are accompanied by imagery.)

As before, Prinz can and will contradict Siewert and say that there must be imagery in every such case. But again, what underwrites the must? Absent an independent argument, it is ad hoc.

Prinz sees an introspective stalemate and offers to break it by offering his five concluding arguments. I agree the arguments have some weight. Whether they will change a given expansionist mind depends on how confident the expansionist is that s/he is introspecting correctly.

An exceptionally useful and characteristically lucid reply from Bill. I am grateful for the reference back to Lormand (a forgotten ally) and for a survey of some arguments I neglected. Let me address these.

For tip of the tongue cases, I would point out that there is a rich sensory, motor, and affective phenomenology. We say related words to ourselves, we call the first letter, we try making speech sounds, we feel frustration. Of course we also know the meaning, and this may present itself to us in phenomenology by means of imagery or verbal description. If I forget Bill’s name, I might imagine his mustache or think, “the sage of Carolina” or stammer, “L-, L-, L-, argh! Lenin? Lyndon? Logan? Damnit!”

On the attitudes, I think these have an emotional phenomenology. Doubt and disappointment are emotional states, and I think emotions are felt as changes in the body. Insert long Jamesian yarn here. Likewise for changes in intensity. A firmly held belief is experienced with a kind of arousal characteristic of conviction. If you don’t believe the attitudes have distinctive bodily markers think about how easily they can be conveyed by vocal intonation.

On Siewert’s sudden onset cases, i can report only that I don’t find these phenomenally familiar. I can imagine suddenly recalling that I have an appointment without associated words or imagery, “Damn! My proctology appointment!” I would describe the imagery. In any case, this is clash of intuitions and I’d welcome suggestions on how to adjudicate. If we have any sense that the thought proceeds the imagery it may stem from the fact that there are usually little things that trigger the thought. When someone mentions that it is Tuesday, you may suddenly recall the appointment, because of an associative link between “Tuesday” and some information in your calendar. The rapid move from the name of the say to the verbalized realization may give rise to the sense that *something* preceded the verbalized realization. It was not a conscious thought, however. Just the usually benign word “Tuesday.”

I agree with Bill that I would have no case for the “must” in my restrictionism if I could show only that imagistic reductions were *possible*. As he realizes, the arguments in the end are supposed to tip the balance in an intuition stalemate. As I see the dialectic, if restricitivsm is possible, then we should embrace it on, among others, parsimony grounds. In that sense, I’d say I’m a methodological restrictivist. I treat it as the default view and wait to be budged into the bulge.

I would like to emphasize two points made by Lycan. If one is a higher-order theorist, rather than an AIR theorist, one will think that there is a common mechanism that accounts for both kinds of consciousness. So what one’s theory of consciousness is will very much effect one’s intuitions about whether there is a cost in this area. Second, I think that Goldman’s Mary-like thought experiments have been under emphasized in the literature on this. It really seems unacceptable to have to say that someone who had never had a conscious thought would have no change in what it was like for them when they suddenly did come to have a conscious thought. They were a zombie before the thought was conscious, and they are a zombie afterwards. Doesn’t that sound odd? Isn’t the fact that we can make sense of mary-like cases for thoughts evidence that we do employ some notion of cognitive phenomenology?

On my view, cognitive phenomenology attaches to the mental attitudes that we take towards various represented propositions. So, to believe that p is, roughly, to have some level of a subjective feeling of certainty about p. One feels as though p were true, so to speak. This might be supported by work on delusional beliefs. Sometimes people report that they are able to tell the difference between their ‘normal’ everyday beliefs and their delusions ones. How would they be able to do this? They may just be inferring that a certain belief is a “rational outlier” but they often describe these beliefs as “feeling differently” than their regular beliefs. One way of thinking about what is going on in these cases is as belief asymbolia, to coin a phrase. That is, it may be the case that these beliefs lack the distinctive phenomenology associated with ordinary beliefs. This would explain why they don’t act on these delusional beliefs. They don’t really act as though they think they are true. If this kind of view were right then we could answer Jesse’s first argument.

Finally, pressing Galen’s general line of attack, I would ask Jesse what he thinks about moral phenomenology. I think that Kant’s notion of ‘respect for the CI’ boils down to a kind of cognitive phenomenology (a ‘sense of duty’), which in turn, I think, turns out to be an instance of what we might call rational phenomenology more generally. When one reasons from P–>Q, and P one feels compelled to accept Q. Even if Q is deeply at odds with your world view, sense of self, or what have you, one feels “forced” to accept Q given that one accepts P –>Q and P. What sensory experience can we identify these with? or do you deny that there is this sort of phenomenology?

Many rich insights here from Richard, and a gorgeous coinage (belief asymbolia).

On HOT vs. AIR, fully agreed. These are not theory-neutral conclusions, and my intuitions are colored by (I would say informed by) the theory of consciousness I endorse. So much so that I see that apparent lack of cognitive phenomenology as a problem for HOT theories. Badly stated, though, this begs the question.

On cognitive Mary, I’m inclined to say that discovery of a first-time attitude is like discovery of a first time emotion. Just as Mary can learn what love is by falling in love for the first time, she can have a first bout of perplexity. Both are emotions and all emotions are embodied.

And this leads me to say something similar about delusions (a very fruitful topic in this area that Richard introduced into our discussion). I think there is a feeling of believing, and that that feeling can attach itself to things for which one has no good evidence. I think I agree with Richard on the phenomenon, but disagree with the claim that the phenomenology of believing is not sensory. I think it is. I think it is bodily. I like the suggestion that there may be different belief-like feelings and some may not lead to action. Food for thought.

On moral (and logical) phenomenology, Richard should again be applauded for enriching the discussion. I am a Humean about morals, so I think feeling that something in morally good or bad or required involves strongly felt (and embodied emotions). Feelings of obligation may involved anticipatory guilt, for example, or a desire to act. Respect for duty may involve a feeling of respect when confronted with a command and commands can be recognized by their affective force. Of course, such feelings do not give these rules their modal force–there is no feeling of necessity–but they give them strong motivational force, and that’s all, I think, we find in the phenomenology. Logical inferences are a bit different. “Primitive compulsions” in Peacocke’s sense, may infuse our modus ponens inferences, and these compulsions may involve a process of automatic belief formation. Once we believe P->Q and P, we may feel compelled to believe that Q. When this doesn’t happen (Q may be something horrible), we may still observe that we *should* believe Q, and this may be felt in the form of dissonance between our non-Q thoughts and the intruding Q thought, or else a skeptical attention delivered upon the premises.

To say that out attitudes and inferences are explained by affect, and that the affective states are embodied is, of course, hugely controversial, and I owe a story about that. I’ve written a bit on the topic, but woefully little, and would welcome further investigation from others. Psychologists talk about “feelings of knowing” and I think feeling talk something we need to push into other attitudinal arenas.

In patients with hemifield neglect, they are not conscious of any information presented to their left visual field. However, in one experiment these patients were shown two pictures of a house, identical except that one had flames pouring from a window on the left side. The patients insisted that the pictures were identical, but still said they would prefer to live in the one that was not on fire. While this is not in any way conclusive, it still seems to suggest that there may be different processes for the consciousness of sensory information and the consciousness of cognitive information. For while the patient appeared to lack all sensory consciousness, the patient still maintained consciousness of thoughts related to the sensory input.

Simply because cognitive consciousness needs sensory states, does not necessarily mean cognitive consciousness is nothing more than sensory consciousness. I can imagine hearing the word “house”, or I can imagine reading the word “house”, or even imagine seeing a house or many different types of houses. But these all seem to be sensory expressions linked together by an intangible cognitive state. Now, are we conscious of this cognitive state? If what you mean by “conscious” is that it can be accessed, or even known, in the absence of sensory constructs, then I would say it is highly unlikely. However, I am writing about it, we are discussing it right now, and we seem to be aware of its existence. So in that sense, yes we are at least partially conscious of our cognitive states.

An interesting experiment would be to take an fMRI in subjects performing tasks that are primarily cognitive, rather than sensory (perhaps something like a math problem? or recalling a piece of literature from memory?). One would have to blindfold the subject and use earplugs to prevent interference from the environment, of course. But in taking this fMRI we would be able to see the full extent that our cognitive consciousness relies on our sensory systems within the brain. Once again, I doubt that this would be conclusive evidence, but it would certainly be a step in the right direction.

Thanks Myranda (if I may). The argument for neglect is ingenious. My interpretation of the case is that these patients have no cognitive consciousness of the flames. If they did, they might report them or offer explanations of their preference that made reference to danger. Instead, they seem to confabulate.

I really like the exercise of thinking about how we grasp a common element across different houses and manifestations of the word “house.” There is a debate in cognitive neuroscience about whether there are meaning-centers in the brain the contain abstract representations of meanings. I’m on the other side of that debate. I think meanings are grounded in perception. But that puts me in the embarrassing situation of saying that there is no single thing we grasp, phenomenal or otherwise, across different house encounters—no mental symbol that arises for every mansion, shack, and brownstone. I’m inclined to say that what comes to mind for each instance is (some subset of) the whole family. Which is to say, each house brings others to mind, as well as the word “house.” So the common denominator is not a single mental symbol, but a shared web of association. I’d welcome ways to test between these alternatives.

VS Ramachandran’s work on synaesthesia also seems relevant here, as it offers an extreme case of the interpenetration of abstract meaning with sensory perception, one that appears to arise from an overabundance of neural connections in one or more areas of the temporal lobe. As Ramachandran speculates, this supposed anomaly may have a great deal to teach us about more ordinary kinds of cognition, especially about metaphorical thought, in which original fusions of abstract ideas with sensory images can acquire more than cumulative power. A rose in Shakespeare’s hand (or on his tongue) has a je ne sais qualia that no other rose can match.

Gretchen gets the prize for “je ne sais qualia.” Hard to surpass that one. Also, I’m grateful for the suggestion that synesthesia may be instructive here. One might say that restrictivists treat all thought as synesthetic in some sense. Very intriguing insight.

Thank you for your reply to my comment above, Jesse. I’m still not convinced that either perception or emotion, not to mention consciousness generally, is sensation-based. I find Galen Strawson’s remarks above applicable, mutatis mutandis, to emotion, and Gretchen Icenogle’s to another point I would like to make about perception a la J.J. Gibson. Gibson maintained that seeing the visual (or other sensory) field was actually an achievement. Example: The art student learning to use her thumb as a common measure of the angular sizes of distant objects. In fact, it was the discovery of the visual field that turned me into a philosopher, for it flipped some of my most basic assumptions on their head. In effect I was discovering my own mind (later I was to discover more of it during yoga meditation: the blooming buzzing confusion of thoughts), the sensory part of which became more salient to me than the “external” physical world it presumably mediated. This is of course the Argument from Illusion. And it is a short step from there to Berkeleyan idealism — a common infatuation of novice epistemologists. “But when I became a man, I put away childish things.” It is interesting to note that Gibson himself underwent the shift of his own theoretical vision (in the opposite direction from the idealist) between his first and second books; for The Perception of the Visual World (1950) gave pride of place to the visual field, while The Senses Considered as Perceptual Systems (1966) brought the stimulus array to the fore. An early and late Gibson, as it were.

Seeing the field brings to mind another form of restrictivism. Just as I think we don’t have cognitive phenomenology, I think we don’t have experience of the self. There is no self-consciousness. But we can experience the self indirectly as a limit (think Schopenhauer), and the visual field in one place where than encounter becomes vivid, as Joel’s remarks bring out. I won’t be able to persuade you, Joel, but I did want to thank you for giving us another Gibsonian morsel to savor.

In response to Jesse Prinz’s essay, I will discuss four interrelated themes. Overall, I am generally sympathetic with his approach to the nature and neurophysiology of consciousness but remain somewhat unconvinced by his “restrictivism.”

1. First, I believe that Prinz has explicitly stated elsewhere that the “intermediate level” is necessary (but not sufficient) for having conscious states. The question then arises as to what else is needed for sufficiency. I suggest that something like the higher-order thought (HOT) theory of consciousness might be useful here (even though Prinz is not a HOT theorist). (HOT theory is most prominently advanced by Rosenthal 2005. See also Gennaro 2004, forthcoming). HOT theorists often start with a highly intuitive claim that has come to be known as the Transitivity Principle (TP):

(TP) A conscious state is a state whose subject is, in some way, aware of being in it.

One motivation for HOT theory is the desire to use TP to explain what differentiates conscious and unconscious mental states. When one has a conscious state, one is aware of being in that state. For example, if I have a conscious desire or pain, I am aware of having that desire or pain. Conversely, the idea that I could have a conscious state while totally unaware of being in that state seems very odd. A mental state of which the subject is completely unaware is clearly an unconscious state. For example, I would not be aware of having a subliminal perception and thus it is an unconscious perception. [When the HOT is itself conscious, there is a yet higher-order (or third-order) thought directed at the second-order state. In this case, we have introspection which involves a conscious HOT directed at a mental state.]

On the cognitive level, we might think of an unconscious HOT as a kind of top-down attention which seems to fit nicely with some of what Prinz says in his essay. On my view at least, this would still not imply that the neural level realization of conscious states would therefore be too “high.” (I will return to the neural question below.) HOTs are also not themselves conscious when one has first-order conscious states. So I wonder if Prinz still thinks that this is the wrong path to take and, if so, why. It seems to me that the two theories could nicely complement each other.

Interestingly, another central motivation for HOT theory is that it purports to help explain how the acquisition and application of concepts can transform our phenomenological experience. Rosenthal invokes this idea with the help of several well-known examples, such as the way that acquiring various concepts from a wine tasting course will lead to different experiences than those enjoyed before the course. I may acquire more fine-grained wine-related concepts, such as “dry” and “heavy,” which in turn can figure into my HOTs and thus alter my conscious experiences. I will literally have different conscious states due to the change in my conceptual repertoire. As we acquire more concepts, we have more fine grained experiences and thus experience more qualitative complexities.

Conversely, those with a more limited conceptual repertoire, such as infants and animals, will have a more course grained set of experiences. Prinz seems sympathetic to this line of thought, such as when he discusses Bayne’s expansionism and visual agnosia in section 3 of his essay. Prinz acknowledges that “phenomenological change” can result from a kind of top-down meaning or knowledge change. He thinks that restrictivists should at least admit that thinking has an impact on phenomenology. I agree here.

2. Second, following on the above themes, I wonder if Prinz might even consider accepting something even stronger, namely, conceptualism, which is the view that all conscious experience is entirely structured by concepts possessed by the subject.

We might define conceptualism as follows:

(CON) Whenever a subject S has a perceptual experience e, the content c (of e) is fully specifiable in terms of the concepts possessed by S.

I believe that CON is true. My point here, however, is that one motivation for it also stems from the widely held observation that concept acquisition colors and shapes the very conscious experiences we have. It seems reasonable to suppose that when one has a perceptual experience e, one understands or appreciates the content c of e in at least some way, which, in turn, requires having concepts. Similarly, the phenomenon of “seeing-as” whereby one subject, perhaps with more knowledge, might perceive an object as a tree whereas another person might only see it as a shrub. This phenomenon is particularly noticeable in cases of perceiving ambiguous figures, such as the well-known vase-two faces image.

Prinz also discusses visual agnosia, or more specifically, associative agnosia, which at least seems to be a case where a subject has a conscious experience of an object without any conceptualization of the incoming visual information. I agree with Prinz against Bayne that this does not force us to accept cognitive phenomenology. Nonetheless, a HOT theorist or a conceptualist might still insist that there must be some HOT in order for there to be a conscious state at all. So a HOT theorist can hold that an abnormal or less robust HOT is present in such cases, which reflects the way that the subject is experiencing the object, such as a whistle or paintbrush. If one experiences object O only as having certain parts or fragments, then those concepts will be in the relevant HOT. For example, if the agnosic cannot visually recognize a whistle, then perhaps only the concepts SILVER, ROUNDISH, and/or OBJECT are applied to O in these abnormal cases. A conceptualist can simply say that the content of the experience in question needs to reflect concepts possessed and applied by the subject. Interestingly, Farah (2004, chapter six) makes it clear that associative agnosics do not really have normal perception merely with the elimination of concept deployment. They do not perceive things just like others save for a recognitional element.

Thus: Why not go further and adopt conceptualism? Why not hold that the concepts and thinking in question are really more “constitutive” of conscious states, as opposed to the weaker “causal” relation. Perhaps this is just out of the question for a current day “empiricist.”

3. Third, returning to Prinz’s “intermediate level” and the neurophysiology, we might take the key question to be: How widely distributed, or “global,” are conscious states? I agree that conscious states, including some HOTs, need not occur in “higher” brain areas such as the IT and the prefrontal cortex (PFC). Thus, even though HOT theory demands that conscious states are distributed to some degree, a more moderate global view is preferable, especially with respect to first-order conscious states.

Some further support for the view that conscious states can occur without PFC activity is as follows:

Rafael Malach and colleagues show that when subjects are engaged in a perceptual task or absorbed in watching a movie, there is widespread neural activation but little PFC activity (Grill-Spector & Malach 2004). Although some other studies do show PFC activation, this is mainly because of the need for subjects to report their experiences. The PFC is likely to be activated when there is introspection and reasoning, not merely when there are outer-directed conscious states (especially during demanding perceptual tasks). These are clearly more sophisticated psychological capacities than merely having conscious states. Zeki has also cited evidence that the frontal cortex is engaged only when reportability is part of the conscious experience and all human color imaging experiments have been unanimous in not showing any particular activation of the frontal lobes.

So I wonder: On Prinz’s view, what exactly is the role of the PFC in consciousness? Does he agree that first-order (i.e. world directed) conscious states need not involve the PFC at all? It seems to me that the PFC has more to do with introspection, reasoning, and reportability.

4. Finally, let’s look more directly to “cognitive phenomenology” (CP) which is also sometimes called “phenomenal intentionality.” I am somewhat more sympathetic to cognitive phenomenology than Prinz:

It is still not clear to me that resorting to associated “mental or verbal imagery” can always fully account for all putative instances of CP. And claiming, in essence, that “all thinking is unconscious” seems much too strong to me. Can’t we at least sometimes have first-order conscious thoughts, say, directed at distant objects or even fictional entities? Don’t we at least sometimes introspect one of our beliefs or thoughts such that they are the objects of conscious thought (and thus conscious at least in that sense)? I confess, however, that I am not quite sure how to settle this issue.