from the National Humanities Center |

|

| |

|

|

| NHC Home |

|

The Foreign Missionary Movement | |||||||||||||

|

in the 19th and early 20th Centuries Daniel H. Bays History Dept. and Asian Studies Program, Calvin College Professor Emeritus, Dept. of History, The University of Kansas ©National Humanities Center |

| ||||||||||||

(part 2 of 4)

Yet, beginning in 1812, Americans did steadily venture forth with their version of the gospel of Protestantism and American civilization, first to India, Burma, and Hawaii, then eventually by 1900 to the Middle East, Africa, and to China, Japan, and Korea in the Far East. In the last decades of the century, American missionary numbers increased substantially (to about 5,000 by 1900), and the major denominations all formed their own missionary societies. But the religious impulse to form voluntary associations continued as well, with new nondenominational "faith" missions such as the Christian and Missionary Alliance and the Sudan Interior Mission adding to the growing stream of American Protestants abroad.

In the decades before about 1870, although the natural tendency was for American Protestants to preach both the evangelical Protestant gospel of individual conversion and regeneration and the secular gospel of American values and institutions, there was some consciousness of the difference between the two, and debate occurred over the appropriateness of expecting the "heathen" to become like Americans. Some made the case that it was enough that they become Christians, and that their culture should not be tampered with, or at least not extensively altered. At midcentury Rufus Anderson, the longtime (1826-1866) foreign secretary of the ABCFM (American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions) attempted to limit the tasks of cultural transformation attempted by his workers, strongly advocating that after preaching the religious gospel, the missionaries should leave, ensuring the continuity of native culture, with its own (hopefully now Christianized) leaders and features. He even insisted on the closing down of schools, as ancillary to the proper main task of missionaries.

Christian baptism,

China, ca. 1910

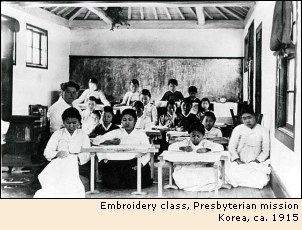

Anderson seems to us today to be more sensitive than many of his day to a form of "multiculturalism" and respect for indigenous peoples. But after 1870 the tide went strongly in the other direction; that is, for missionaries to preach civilization and provide training for it, such as schools and medicine, as well as to preach Christ. Moreover, other features of the growth of the foreign mission movement—its size, structure, composition, and momentum—made it increasingly unlikely that American missionaries would just preach the Gospel and move on. The denominational societies formed after midcentury naturally developedprograms, such as in education, medicine, or relief work, with their own built-in longevity (you couldn't start a school and then immediately turn it over to untrained natives). The increase in number of missionaries meant that more lay people went to the mission field. For the most part only ordained men could perform certain religious functions such as baptism, so lay missionaries naturally gravitated to the nonreligious activities that became institutionalized and long-term.

One of the striking features of the American foreign missionary force in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was that women composed about sixty percent of it. Some were missionary wives (most of whom played active roles in the mission), but many were single women missionaries. It may be true that women could find more challenging and satisfying vocations on the foreign mission field than they could at home during these decades.

Missionary Emily Hartwell of the Women's Board of Missions with Chinese students, Foochow Mission, China, 1902

Finally, late in the century there was a visible rise in American national self-confidence and an assumption that American values and institutions were as valid as the Christian gospel. This was the age of European empire-building around the world, and the U.S. was not immune to the trend; American national power also expanded by the end of the century, resulting in acquisition of an empire in the 1890s (Hawaii and the Philippines). In this context it was easy for American missionaries to conflate the Protestant responsibility to evangelize the world and the assumption that the U.S. was a special model of civic virtue and republican civilization.

TeacherServe Home Page

National Humanities Center Home Page

7 Alexander Drive, P.O. Box 12256

Research Triangle Park, North Carolina 27709

Phone: (919) 549-0661 Fax: (919) 990-8535

Revised: September 2005

nationalhumanitiescenter.org