from the National Humanities Center |

|

| |

|

|

| NHC Home |

| African American Christianity, Pt. II: From the Civil War | |||||||||||||||

|

to the Great Migration, 1865-1920 Laurie Maffly-Kipp University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill ©National Humanities Center |

| ||||||||||||||

(part 1 of 3)

The Era of Emancipation posed distinctive religious challenges for northern and southern African Americans. When the Civil War finally brought freedom to previously enslaved peoples, the task of organizing religious communities was only one element of the larger need to create new lives—to reunite families, to find jobs, and to figure out what it would mean to live in the United States as citizens rather than property. Northern blacks, for their part, having already gained freedom, saw Emancipation as an enormous logistical challenge—how could black Protestants meet the many needs of newly freed slaves and truly welcome them into a Christian community? And for both, Emancipation promised a meeting between two African American religious traditions that had moved far apart, in terms of both theology and ritual, in the previous seventy years.

In significant respects, the story of African American religion between Emancipation and the northern migration that began just prior to World War I is a tale of regionally distinctive communities that found several areas of common cause, not the least of which were the advent of Jim Crow and lynching as ominous new forms of racism. But an understanding of religious experience in this era must also be supplemented by the complexities of the many internal boundaries in African American life in both the north and south—class divisions, rural/urban differences, and gender issues that accompanied the dawn of freedom.

Class Divisions (Emancipation in the North and South)

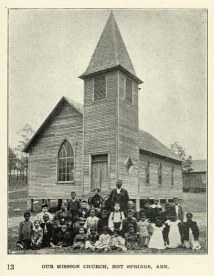

A.M.E. mission church, Arkansas, late 1890s

A long history of antislavery and political activity among northern black Protestants had convinced them that they could play a major role in the adjustment of the four million freed slaves to American life. In a massive missionary effort, northern black churches established missions to their southern counterparts, resulting in the dynamic growth of independent black churches in the southern states between 1865 and 1900. Predominantly white denominations, such as the Presbyterian, Congregational, and Episcopal churches, also sponsored missions, opened schools for freed slaves, and aided the general welfare of southern blacks, but the majority of African-Americans chose to join the independent black denominations founded in the northern states during the antebellum era.

A.M.E. bishops, with scenes of social and educational programs, 1876 Within a decade the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) and the African Methodist Episcopal Zion (AMEZ) churches claimed southern membership in the hundreds of thousands, far outstripping that of any other organizations. They were quickly joined in 1870 by a new southern-based denomination, the Colored (now "Christian") Methodist Episcopal Church, founded by indigenous southern black leaders. Finally, in 1894 black Baptists formed the National Baptist Convention, an organization that is currently the largest black religious organization in the United States.

In many ways this missionary effort was enormously successful. It helped finance and build new churches and schools, it facilitated a remarkable increase in southern black literacy (from 5% in 1870 to approximately 70% by 1900), and, as had been the case in the north, it promoted the rise of many African American leaders who worked well outside the sphere of the church in politics, education, and other professions. But it also created many tensions between northerners, who saw themselves in many respects as the superiors and mentors of their less fortunate southern brethren, and southerners, who had their own ideas about how to worship, work, and live.

John Antrobus, A Plantation Burial, scene in Louisiana, 1860

Augusta, GeorgiaAlfred Heber Hutty, Voodoo Ritual

scene in lowcountry South Carolina (undated)Not all ex-slaves welcomed the "help" of the northerners, black or white, particularly because most northern blacks (like whites) saw southern black worship as hopelessly "heathen." Missionaries like Daniel Payne, an AME bishop, took it as their task to educate southern blacks about what "true" Christianity looked like; they wanted to convince ex-slaves to give up any remnants of African practices (such as drumming, dancing, or moaning) and embrace a more sedate, intellectual style of religion. Educational differences played a role in this tension as well. Southern blacks, most of whom had been forbidden from learning to read, saw religion as a matter of oral tradition and immediate experience and emotion. Northerners, however, stressed that one could not truly be Christian unless one was able to read the Bible and understand the creeds and written literature that accompanied a more textually-oriented religious system.

TeacherServe Home Page

National Humanities Center Home Page

7 Alexander Drive, P.O. Box 12256

Research Triangle Park, North Carolina 27709

Phone: (919) 549-0661 Fax: (919) 990-8535

Revised: June 2004

nationalhumanitiescenter.org