from the National Humanities Center |

|

| |

|

|

| NHC Home |

|

African American Christianity, Pt. II: From the Civil War to the Great Migration, 1865-1920 Laurie Maffly-Kipp University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill ©National Humanities Center |

|

(part 3 of 3)

Guiding Student Discussion

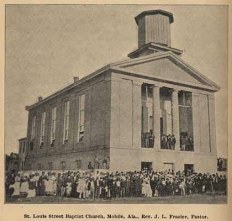

St. Louis Street Baptist Church

Mobile, Alabama, ca. 1895This period presents a great challenge in the classroom, if only because the material follows no easy narrative. Scholars have reached little consensus, and in some cases, little research has been done that can shed light on the outlines of black church life in this era beyond the most general statements. For this reason, emphasizing issues of what unifies blacks, and what diversifies them, is a fruitful way of pointing out similarities and differences. I would also strongly urge a biographical approach to this period, if only because it is easier to see how some of these tensions get worked out in an individual life than to talk about them abstractly. A good place to begin, in this respect, might be with Booker T. Washington, W. E. B. Du Bois, or Ida B. Wells-Barnett, all of whom were involved with organized religion at points in their careers (see Primary Sources).

Three areas of discussion may be particularly fruitful.

Bishop Daniel A. Payne

excerpt on "praying and singing bands" from Recollection of Seventy Years, 1888

full text· The conflicts that arose between black northern missionaries and southern blacks. It is useful to employ writings by participants here, particularly the work of Daniel Alexander Payne, who published several histories of the church in addition to memoirs that recount his experiences in the south (see Primary Sources). Hopefully, students can be coaxed into a discussion of these two very different understandings of what constitutes "real" religion—experience vs. education, rationality vs. emotional intensity, etc.—and can be made to see the internal logic of each. The danger is that they may come away seeing the northerners as "sell-outs" or simply traditional stick-in-the-muds who are trying to squelch honest religious experience, rather than understanding the context for the northern brand of piety. So you may need to work hard to point out that even people sitting quietly in their pews can be having a "real" religious experience.

Open air revival of the Apostolic Faith Church, Portland, Oregon, 1907 · The emergence of the holiness-

pentecostal movement. Since this is a movement that cuts across denominations and reflects a religious style as much as a set of beliefs, it can be a bit abstract to talk about. It might be useful to discuss why the Pentecostals rather quickly break down into racially-based denominations, after beginning in a very multiracial way. What does this say about racial divisions in our society? Why are they still divided, long after segregation in other places has been abolished? What might have attracted people in 1906 (at the height of lynching and Jim Crow) to a multiracial movement in the first place?

Ida B. Wells-Barnett, ca. 1890s

excerpts on churches' response to lynching from her autobiography Crusade for Justice· The plight of middle-class black Protestants after the 1870s. This tends to be the great forgotten story of African American religious life, in part because they seem relatively conservative in our day and age (and thus haven't inspired many historians to recover their story). But they also blended a remarkable mixture of organizational strength and savvy with enduring political protest over segregation. Women in the movement are particularly notable as some of the first African American women to gain an organized social voice in our society. What did the church provide that allowed them to do this, and to sustain themselves in the face of continued oppression? In this regard, I find the autobiography of Ida B. Wells-Barnett to be particularly moving (see Primary Sources).

Historians Debate

There are a few survey studies of the Reconstruction Era that are comprehensive. On this period, see William E. Montgomery, Under Their Own Vine and Fig Tree: The African-American Church in the South, 1865-1900 (1993) for an overview. On Methodists, see Reginald Hildebrand, The Times Were Strange and Stirring:Methodist Preachers and the Crisis of Emancipation (1995). On Baptists, the best sources are James Washington, Frustrated Fellowship: The Black Baptist Quest for Social Power (1986), and Paul Harvey, Redeeming the South: Religious Cultures and Racial Identities among Southern Baptists, 1865-1925 (1997).

The Holiness-Pentecostal movement has been understudied, particularly the African American side of the story. For an overview, see Grant Wacker, Heaven Below: Early Pentecostals and American Culture (2001) and Vinson Synan, The Holiness-Pentecostal Tradition: Charismatic Movements in the Twentieth Century (1997/1971). On African-American Pentecostals, see Cheryl J. Sanders, Saints in Exile: The Holiness-Pentecostal Experience in African American Religion and Culture (1996).

Although the full effects of the "Great Migration" of southern blacks to northern cities were not apparent until the 1920s, there are several excellent introductions available that cover the religious origins and spiritual dimensions of the move. See Milton C. Sernett, Bound for the Promised Land: African American Religion and the Great Migration (1997), and Nicholas Lemann, The Promised Land: The Great Black Migration and How It Changed America (1991).

Women noted in C. O. Booth, The Cyclopedia of the Colored Baptists of Alabama: Their Leaders and Their Work, 1895, full text The most intriguing recent scholarship on African-American religions has dealt with the relatively neglected stories of northern free blacks and women in black churches. Since the mid-1980s, scholars have highlighted religion as one aspect of the many identities assumed by African Americans; they have helpfully focused attention on issues of class (middle-class versus poorer blacks), gender, and region within black churches, as well as shedding new light on issues of race. Recent research accordingly has dealt with the post-Civil War era as a time of tremendous strain and transformation within African-American culture, as well as between whites and blacks, with the church as a primary political and cultural meeting point for many types of people. While much remains to be uncovered in this area, the best starting points are Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham’s Righteous Discontent: The Women's Movement in the Black Baptist Church 1880-1920 (1993), and the essays in Judith Weisenfeld and Richard Newman, eds., This Far By Faith: Readings in African-American Women’s Religious Autobiography (1996).

Links to online resources

Primary Sources

Works Cited

Illustration Credits

Comments & Questions

Laurie Maffly-Kipp is Associate Professor of American Religious Studies in the Department of Religious Studies of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She was a Fellow at the National Humanities Center in 1993-94. Dr. Maffly-Kipp is the author of Religion and Society in Frontier California (1990) and her current book project is African-American Communal Narratives: Religion, Race, and Memory in Nineteenth-Century America. Dr. Maffly-Kipp is a consultant to two major documentary projects: African-American Religion: A Documentary History Project, eds. A. J. Raboteau and D. W. Wills, and The Church in the Southern Black Community (1998/99 Award Winner of The Library of Congress/Ameritech National Digital Library Competition). She serves on the editorial boards for Church History and The North Star: A Journal of African-American Religious History.

Address comments or questions to Professor Maffly-Kipp through TeacherServe "Comments and Questions."

TeacherServe Home Page

National Humanities Center Home Page

7 Alexander Drive, P.O. Box 12256

Research Triangle Park, North Carolina 27709

Phone: (919) 549-0661 Fax: (919) 990-8535

Revised: June 2004

nationalhumanitiescenter.org