The American Civil War: An Environmental View

Jack Temple Kirby, Miami University

©National Humanities Center |

|

(part 4 of 6)

Reservations

So might end a grisly introductory overview of our hypothetical EPA report. Further, deeper, longterm analysis should probably begin with a reminder to students that the American Civil War was a "total" one—that is, unrelenting violence against not only enemy soldiers, but upon the Confederate armies' very capacities to wage war, violence against civilians, cities, farms, animals, | | . . . in several senses the Civil War's massive damage was temporary and arguably, not very significant at all. |

the landscape itself. Victory resolved profound national issues, solidifying the supremacy of nation over state, most importantly abolishing slavery forever and liberating nearly four millions of living people. Awesome destruction and unspeakable horror are thus usually justified. Total war's awful technological and political future, in the twentieth century, would be justified similarly.

Meanwhile, the longterm aspect of our report's second chapter may well surprise, because in several senses the Civil War's massive damage was temporary and arguably, not very significant at all. Consider the following evidence of southern "progress" after the war—in farmland, forests, and the lumber industry.

|

|

Frank Leslie's Illustrated

Newspaper, 24 June 1882

[note skull at lower right]

| Library of Congress

|

|

|

|

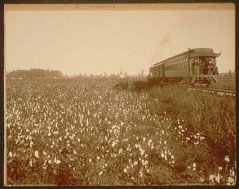

1. Farmland. Despite the South's enormous losses of young men, despite the carnage of horses and mules, and despite damage and ruination of thousands of farms, the South not only remained an agricultural region of global importance, but rapidly expanded its commodity production and exports during the postwar decades and long thereafter. Astoundingly, southern cotton harvests at the end of the nineteenth century were triple 1860s production. Such a remarkable expansion was accomplished in part by reconstruction of antebellum farms and plantations, but more by territorial expansion, accomplished through (1) the clearing of swampy forests, notably in the Yazoo-Mississippi Delta (mostly during the 1880s) and later, across the Mississippi in northeastern Arkansas and southeastern Missouri; (2) the deforesting of upper piedmont and low mountain landscapes, e.g., in northwestern Georgia and northern Arkansas; and then (3) a huge invasion of cotton culture into the subhumid Southwest—central Oklahoma and Texas and, later, in the twentieth century, in the High Southern Plains themselves.

A few postbellum cotton growers were newcomers; most were white and black southerners, mobile people, some rich but most poor, scions of large families that survived the war and produced yet larger families of their own. The postbellum southern population boomed, and labor was cheap, the war's great losses no impediment to vast economic growth. Likewise the supply of agricultural power—horses and especially mules—was quickly recovered and expanded. These were the living engines of deforestation and cotton's expansion. Missouri, Kentucky, and Tennessee were postbellum animal breeders, as before the war, and early in the twentieth century Texas emerged as premier breeder (as well as cotton-producer).

2. Forests. Edmund Ruffin and other eastern farmers lamented the disappearance of "good" trees long before the war. They meant deciduous hardwoods appropriate to building, especially fences. The typical southern farmer's shifting system of fieldmaking involved setting fire to the woods, cultivating the new field for a few years, abandoning it to a succession that in most places yielded loblolly pines, then returning to the original plot and firing it again. Deciduous trees had little or no time to mature and shade out the pines. So, if we share Ruffin's valuation of deciduous above coniferous trees, much of the South had been undergoing profound forest degradation for at least a thousand years, since Native Americans practiced fire/shifting culture before the Europeans and Africans arrived. The Civil War took (one can only guess) hundreds of thousands of trees of many species, pines especially. Then postbellum clearing for agricultural expansion and the construction of new railroads (especially across the southern Appalachians) must have taken many more, probably exceeding wartime destruction. Trees have ever been the enemy of civilization. Clearcutting hilly and mountainous terrain always invites soil erosion, too, another longterm environmental impact, and one seldom addressed before the New Deal.

|

Pine region, West Virginia,

ca. 1892

| Library of Congress

|

"Still, the southern forests remained so vast thirty years after the Civil War that the well-organized and technologically proficient U.S. timber industry turned to the Southeast

during the 1890s."

|

|

|

|

Still, the southern forests remained so vast thirty years after the Civil War that the well-organized and technologically proficient U.S. timber industry turned to the Southeast during the 1890s. Frederick Weyerhauser and other entrepreneurs, having already cut down the forests of the upper Great Lakes states, staked out the Pacific Northwest and, simultaneously, the Carolinas, the Gulf Coast, West Virginia, and so on. Most state and national forests in the contemporary South are large tracts long ago clear-cut and abandoned by these entrepreneurs.

3. Lumber heading west. The massive cut-down of American forests during the last third of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century intimately connected to the Civil War. The Homestead Act of 1862 unleashed long pent-up Yankee ambition to colonize western territories with midwestern-style family farms. Southern members of Congress had resisted the scheme because they preferred a Great Plains open to slavery. So when southerners withdrew to their own, Confederate, congress, Yankee ambition was finally realized. By coincidence, a thirty-year-long Union war against Plains Indians began the same year. Near extermination of the Plains' dominant quadruped, the bison, was underway, too, and the first transcontinental railroad was completed only four years after the war ended.

|

|

|

"Now an enormous, virtually treeless landscape awaited transformation into farms and towns, demanding millions of linear feet of imported wood."

|

|

|

|

Now an enormous, virtually treeless landscape awaited transformation into farms and towns, demanding millions of linear feet of imported wood—for housing, barns, fences (even barbed wire must be nailed to posts), churches, town buildings of all sorts, and railway ties. The legendary Paul Bunyan's thousands of real-life lumberjack counterparts first supplied the demand from Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota; then came Bunyan's southern brethren, black and white—sons and grandsons of liberated slaves and soldiers of both sides.

|

Bear Mountain, Pennsylvania, 1879

| Library of Congress |

"Ultimately, it is the nineteenth-century North American

landscape itself that astounds."

|

|

Ultimately, it is the nineteenth-century North American landscape itself that astounds. It fueled an industrial revolution, sustained the massive damage of civil war, yet still had reserve capacity to power the juggernaut of rail, farm, and city-building across the center of the continent. The enormous costs of such heroic feats of construction were publicized with alarm even before the end of the Civil War. In 1864 George Perkins Marsh, an American diplomat in Italy and former congressman from Vermont, published Man and Nature: or Physical Geography as Modified by Human Action, a precocious work still honored by environmentalists, which approached the human-natural world relationship in a manner we would call ecological. Marsh's was not a lonely voice, either. I think it more than coincidental that young John Muir, already alienated by the rapacity of progress, had walked west, to the Sierras, and begun his life's work at wilderness preservation. And Frederick Law Olmsted, already renowned as co-designer of Central Park in Manhattan, spent parts of 1863 and '64 in California, studying the Yosemite Valley and recommending a preservation plan to the state government. One must think, then, that the Civil War is connected, causatively (within a larger context, to be sure) with the emergence of modern nature-protection. This broadest view yields the conclusion—ironic yet a serious one—that the Civil War means practically nothing and nearly everything, environmentally speaking.

Library of Congress  Olmsted, 1893

|

Library of Congress  Marsh, ca. 1850

|

National Park Service  Muir, ca. 1893

|

|

|

TeacherServe Home Page

National Humanities Center

7 Alexander Drive, P.O. Box 12256

Research Triangle Park, North Carolina 27709

Phone: (919) 549-0661 Fax: (919) 990-8535

Revised: July 2001

nationalhumanitiescenter.org |