|

| NHC Home |

|

The American Civil War: An Environmental View Jack Temple Kirby, Miami University ©National Humanities Center |

|

The centennial of the Civil War in the 1960s occasioned defiant displays of the Confederate battle flag, an accelerated and triumphant civil rights movement, and, predictably, opportunistic publication of another huge library of books on the war. My graduate school mentor, trying to encourage his students to undertake research on other subjects, joked that the Civil War era was overcrowded, there being no conceivable niche not already claimed, except, he declared, “The Sex Life of Lincoln’s Doctor’s Dog.” My mentor knew he was wrong. The African-American experience of the war was only then getting sympathetic attention, along with political issues both large and local. Women and the war awaited eager scholars and readers, later. Yet in the nearly four decades since the centennial, demand for old-fashioned (shall I say?) military history and military biography has hardly abated. Environmental history, meanwhile, a subdiscipline born during the 1960s and flourishing modestly since, has yet to impact the Civil War seriously.

More than three decades of accumulated literature in environmental history barely touch the Civil War. The recent historiographies of the war and of “environment” are so curious because they are parallel; that is, they do not intersect. Military historians preoccupied with combat on specific landscapes almost do environmental history, and environmentally-minded readers may deduce from conventional texts ecological aspects of warfare. The historians seem uninterested, however, and few academic military specialists of my acquaintance have read environmental history. On the other side, more than three decades of accumulated literature in environmental history barely touch the Civil War. This is because the bulk of environmental history is western history, set usually beyond the pale of Civil War fighting. The “New Western History” that has provoked so much controversy recently is to a considerable extent environmental, a tragic narrative of human depredations upon semi-arid and arid landscapes. Most historians of environment happen to be westerners, too, and the best graduate programs in the field are in Wisconsin, Kansas, and California. Ergo the parallelism. Easterners (it would seem) must wrench environmental-historical criticism backwards, across the Mississippi.

Toward an Ecological View of the Civil War

An Arkansas classroom

1972National Archives "Everyone understands that humans are connected creatures"

A consciously ecological view of the Civil War is actually required, I think, for two compelling reasons.FIRST: the environmental movement itself. Since World War II and especially since 1970 and the first “Earth Day,” Americans have belonged to a culture steeped in ecological language and politics. Everyone understands that humans are connected creatures, obligated partners in a dynamic natural community. Nature sometimes presents change without human agency, but human action—making civilizations, technology, warfare—has enormous consequences.

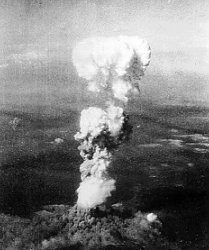

SECOND: the knowledge of war as an ecological disaster. No one alive at the dawn of the twenty-first century, from the oldest among us to our most immature students, can conceive of war without environmental danger if not disaster. Students may know from reading or film about World War I’s chlorine and mustard gases, and their effects upon men and horses on the Western Front, and about buried, still unexploded shells from 1914-1918 in the farmlands of eastern France and Belgium. More familiar are the atomic blasts of August 1945 in southern Japan, obliterating concrete and steel buildings, trees, humans, dogs and cats, while survivors in outlying places

suffered disfiguring burns and ultimately fatal radiation sickness. The United States’ employment in Vietnam of the defoliant Agent Orange, a derivative of domestic cotton culture, seems now a particularly macabre exposition of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962), a classic of contemporary environmentalism. Iraq used deadly chemical agents while warring with Iran during the 1980s, and in 1991 United Nations’ forces on the Arabian peninsula feared the same from Iraq, even as Kuwaiti oil fields and depots exploded, despoiling the air above and the desert below.

Hiroshima, 1945 National Archives "No one alive at the dawn of the twenty-first century . . .

can conceive of war without environmental danger if not disaster."For all its own horrors, the Civil War presented none of the above, and perhaps this is the beginning of students’ orientation to “environment” during the 1860s. They should understand that we must interrogate the past in our own language, trapped (or advantaged?) by the sensibilities of our time while respecting the foreign-ness of the past. What follows, then, represents my re-reading of conventional Civil War history, biased by my green convictions, and informed by my own and a few others’ modest explorations of the war and what we call environment.

| "The Use of the Land" Essays |

| History with Fire in Its Eye |

American Civil War | Roads, Highways, & Ecosystems Essay-Related Links |

TeacherServe Home Page

National Humanities Center

7 Alexander Drive, P.O. Box 12256

Research Triangle Park, North Carolina 27709

Phone: (919) 549-0661 Fax: (919) 990-8535

Revised: July 2001

nationalhumanitiescenter.org