The Columbian Exchange: Plants, Animals, and Disease between the Old and New Worlds

Alfred W. Crosby, Professor Emeritus, University of Texas at Austin

©National Humanities Center

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Photodisc  |

|

| |

"The Amazon has jaguars . . . the Congo leopards." |

|

|

|

For tens of millions of years the dominant pattern of biological evolution on this planet has been one of geographical divergence dictated by the simple fact of

the separateness of the continents. Even where climates have been similar, as in the Amazon and Congo basins, organisms have tended to get more different rather than more alike because they had little or no contact with each other. The

Amazon has jaguars, the Congo leopards.

However,

very, very recently—that is to

say, in the last few thousand years—there has

been a countervailing force, us, or, if you want to be scientific about it, Homo sapiens. We are world-travelers,

|

|

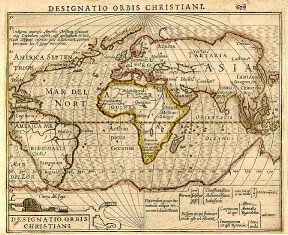

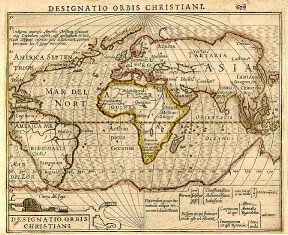

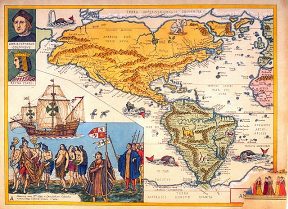

Hondius, 1607

| Yale University Library |

"We are world-travelers, trekkers of deserts and crossers of

oceans. . . . Humans have in the very last tick of time reversed the ancient trend of geographical biodiversification."

|

|

|

|

trekkers of deserts and crossers of

oceans. We have gone to and lived or at least spent some time everywhere, taking with us, intentionally, our crops and domesticated animals and, unintentionally, our weeds, varmints, disease organisms, and such free-loaders

as house sparrows. Humans have in the very last tick of time reversed the ancient trend of geographical biodiversification.

Many of the most spectacular and the most influential examples of this are in the category of the exchange of organisms between the Eastern and Western Hemispheres. It began when the first humans entered the New World a few

millennia ago. These were the Amerindians (or, if you prefer,

proto-Amerindians), and they brought with them a number of other Old World species and subspecies, for instance, themselves, an Old World species, and possibly the domesticated dog, and the tuberculosis bacillus. But these were few in number. The humans in question were hunter-gatherers who had domesticated very few organisms, and who in all probability came to America from Siberia, where the climate kept the number of humans low and the variety

of organisms associated with them to a minimum.

There were other avant garde humans in the Americas, certainly the Vikings about 1,000 CE, possibly

Japanese fishermen, etc., but the tsunami of biological exchange did not begin until 1492. In that year the Europeans initiated contacts across the Atlantic (and, soon after, across the Pacific) which have never ceased. Their motives

were economic, nationalistic, and religious, not biological. Their intentions were to make money, expand empires, and convert heathen, not to spread Old World DNA; but if we take the long view we will see that the most important aspect of their imperialistic advances has been the latter.

|

|

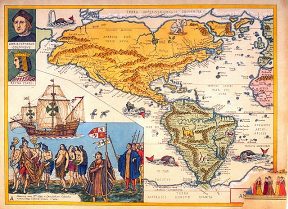

"America," 1586

| Reed College |

". . . the tsunami of biological exchange

did not begin until 1492."

|

|

|

They

off-handedly and often unintentionally effected enormous augmentations and

deletions in the biota of the continents, so enormous it is difficult to

imagine what these biotas were like prior to Columbus, et al. A large tome

would not provide enough space to list the plant, animal, and micro-organism

exchanges, and a thousand volumes would be insufficient to assess their effect.

In the space of this essay, we can only manage to convey an impression of the

magnitude of these biological revolutions.

Jean-Marc Rosier  |

"I recommend that you consider the contrast between the flexibly nosed tapir of South America and

|

Photodisc  |

| the more extravagantly nosed elephant of Africa." |

|

|

|

Let us begin with a thumbnail sketch of the biogeography of the globe when Columbus set sail. Everyone in the Americas was a Amerindian. Everyone in Eurasia and Africa was a person who shared no common ancestor with Amerindians for at the very least 10,000 years. (I omit the subpolar peoples, such as the Inuit, from this analysis because they never stopped passing back and forth across the Bering Strait).

The plants and animals of the tropical continents of Africa and

South America differed sharply from each other and from those in any other

parts of the world. I recommend that you consider the contrast between the

flexibly nosed tapir of South America and the more extravagantly nosed elephant

of Africa. The plants and animals of the more northerly continents, Eurasia and

North America, differed not so sharply, but clearly differed. European bison

and American buffalo (which should also be called bison) were very much alike, but

Europe had nothing like the rattlesnake nor North America anything like the

humped camel.

|

Photodisc  |

| "Europe had nothing like the rattlesnake nor North America anything like the humped camel." |

|

|