Buffalo Tales: The Near-Extermination of the

American Bison

Shepard Krech III, Brown University

©National Humanities Center |

|

(part 1 of 4)

|

Bison, Yellowstone National Park

| NPS |

|

|

|

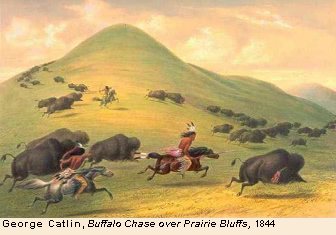

Prior to the arrival of Europeans and their powerful, transforming products, desires, and structures, American Indians possessed extensive knowledge about the environments in which they lived and made sense of living beings in myriad culturally appropriate ways. They drew on an extraordinary variety of animals and plants in daily subsistence; yet specific animals or plants, because of their prominence, came to stand for entire regions and groups of people: seals for Inuit, caribou for northern Indians, acorns and deer for native Californians, salmon for Northwest Coasters, corn for the Southwest Puebloans, Hopi and Zuni. None was more prominent than the buffalo.

The buffalo was first and foremost of utmost significance to people of the plains and prairies. In a very different way, its crucial standing was underscored by native people generally, after the spread of Plains traits and imagery—especially the eagle-feathered bonneted warrior-hunter astride his horse in pursuit of meat and honor—ultimately to symbolize the North American Indian. Moreover, no story of wildlife decline in North America is more widely known than the demise of the buffalo. It is one of the most important stories in the environmental history of North America.

|

ca. 1873

| National Archives

|

"no story of wildlife decline in North America is more widely

known than the demise of the buffalo"

|

|

Buffaloes once ranged much of the continent, from the east to west coasts, and from Canada's Northwest Territories in the north and Mexico in the south. The center of population was the great western grasslands, and the press of new arrivals from Europe soon resulted in their extermination in the peripheries of their territory; east of the Mississippi they were extinct by 1833.

|

|

| What strikes the stranger with most amazement is their immense numbers. I know a million is a great many, but I am confident we saw that number yesterday. Certainly, all we saw could not have stood on ten square miles of ground. Often, the country for miles on either hand seemed quite black with them. |

An Overland Journey, from New York to

San Francisco in the Summer of 1859

Horace Greeley, 1860

full text

|

| Suddenly a cloud of dust rose over its crest, and I heard a rushing noise as of a mighty whirlwind, or the charging tramp of ten thousand horse. I had not time to divine its cause, when a herd of buffalo arose over the summit, and a dense mass, thousand upon thousand, gallopped, with headlong speed, directly upon the spot where I stood. . . . Still onward they came—Heaven protect me! it was a fearful sight. |

"Scenes in the West; or,

A Night on the Santa Fe Trail, No. III,"

Philip St. George Cooke, Southern Literary Messenger, February 1842

full text

|

|

|

From 1600 to 1870, the number of buffaloes was almost always uncertain: observers used language like immense numbers, countless numbers, countless thousands, dense masses, one great mass, herds that blackened the plains, bulls roaring like distant thunder or like a river's rapids, bison in such numbers that they drink a river dry or the ground trembles with vibration when they move. The images were striking. The annual migration across the prairies awed all who experienced it. Because there were so many buffaloes, natural disasters were magnified: thousands, if not tens of thousands, froze to death in blizzards, drowned crossing rotten ice, or mired in muddy bogs.

Estimates of numbers range widely. Some thought (clearly in error) that there were hundreds of millions of even billions; others estimated (far more reasonably) numbers at from 30 to 1000 million in A.D. 1500. Ernest Thompson Seton, the naturalist, was the first to estimate population on the basis of what was called "range allowance" (or carrying capacity) and settled on at least 60 million. Since his day the tendency has been to lower the estimates because bison were unevenly distributed over their range and because drought periodically struck the Plains. According to Dan Flores, an historian, no more than 30 million bison roamed the Plains prior to the arrival of the horse.

|

| Iowa, 1906 |

Library of Congress

|

|

|

Arapaho camp

with buffalo meat drying

Kansas, 1870

enlarge image

| National Archives |

"For thousands of Plains Indians . . .

the buffalo was unquestionably paramount."

|

|

|

|

For thousands of Plains Indians—people like the Blackfeet, Gros Ventre, Assiniboin, Crow, Cheyenne, Shoshoni, Arapaho, various Sioux or Dakota people, Comanche, and others—the buffalo was unquestionably paramount. For many it was "real" food, and they consumed an incredible variety of bison parts: meat, fat, organs, testicles, nose gristle, nipples, blood, milk, marrow, fetus. They had broadly defined canons of edibility but preferred cows over bulls and greatly desired humps, tongues, and fetuses.

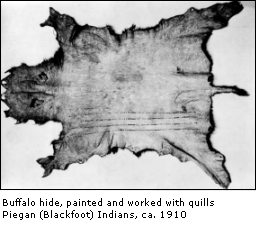

But the buffalo represented more than food. For many it provided over one hundred specific items of material culture. Day or night, Plains Indians could not ever have been out of sight, touch, or smell of some buffalo product. It was the era's Wal-Mart.

Hides

(with bison

hair off) | moccasins, leggings & other clothing, tipi covers & linings, shields, maul covers, cups & kettles, parfleches (carrying cases) |

Robes

(with bison hair on) | winter clothing, gloves, bedding, costumes (ceremonial and decoy) |

| Hair | ropes, stuffing, yarn |

| Sinew | thread, bowstrings, snowshoe webbing |

|

Denver PL

|

|

|

| Horns | arrow points, bow parts, ladles & spoons cups, containers (for tobacco & medicine) |

| Hoofs | rattles, glue |

Tibia &

other bones | brushes, awls, fleshers, other tools |

| Ribs | arrow straighteners |

| Brains | to soften skins |

|

| Fat | paint base |

| Dung | fuel

to polish stone

|

| Teeth | ornaments

|

Paunch &

Large Intestine | containers |

| Gall stones | yellow pigment |

Penis

| glue |

|

TeacherServe Home Page

National Humanities Center

7 Alexander Drive, P.O. Box 12256

Research Triangle Park, North Carolina 27709

Phone: (919) 549-0661 Fax: (919) 990-8535

Revised: July 2001

nationalhumanitiescenter.org |