|

| NHC Home |

|

The Challenge of the Arid West Donald Worster, University of Kansas ©National Humanities Center |

|

(part 4 of 4)

SCHOLARS DEBATE

The first historian to address the challenge of aridity was Walter Prescott Webb in his book The Great Plains (1931), which argued that the natural environment created "an institutional fault-line" across the nation. Laws and technologies developed in humid America could not get over that line, forcing people to make such innovations as barbed wire (to substitute for wooden fences) and windmills (to pump underground water). Webb saw a nation divided by nature and unequal in development. Moreover, he raised a broader question that previous historians had ignored: what is the role of nature in social evolution? That question took on new significance in the Dust Bowl years. Wind erosion and forced migration caused many to question whether westerners themselves had understood their environmental challenges sufficiently and had learned to adapt to drought cycles and aridity. Where Webb had seen a distinctly new region emerging, others saw a failed civilization that had been foretold by Powell.

Kansas (?), n.d. Wichita State University

Dust storm over Phoenix

after a 153-day drought, 1972National Archives "What is the role of nature in social evolution?"

In the early postwar period, Powell's star continued to ascend until he became a shining hero to many scholars and conservationists. They were less interested in the role of nature in history and more in the cultural blinders that Americans wore when they moved west. Two classic works that followed Powell in criticizing maladaptive attitudes were Henry Nash Smith's Virgin Land (1950) and Wallace Stegner's biography of Powell, Beyond the Hundredth Meridian (1954). Both of them found the nation and the region alike to be unrealistic in expectations. Smith showed how an "agrarian myth," joined with imperial ambitions, convinced people that they could create a "garden of the world" where deserts had ruled. Stegner, one of the most influential western voices in the twentieth century, described a battle between, on the one hand, Powell the scientist and, on the other hand, regional political and economic leaders who pursued extravagant dreams of growth.

Palm Springs

California, 1988Paul Starrs "a 'garden of the world' where deserts had ruled"

Following the rise of the environmental movement and the new field of environmental history, scholars have focused more and more on western water politics. Although some still celebrate achievements of the Bureau of Reclamation and other dam-building agencies, most historians have become more critical of how water has been managed in the West. Norris Hundley, author of three books on the subject—The Great Thirst (1992), Water and the West (1975), and Dividing the Waters (1966)—has argued that the government overestimated the amount of water available for use, particularly in the Colorado River, creating serious legal conflicts among the states and between the United States and Mexico. He sees a history of chaos and disorder in water planning—inefficiency, waste, and strife—instead of coordinated development or cooperative spirit.

Jawbone Siphon, part of

Los Angeles aqueduct system, 1988G. Donald Bain "most historians have become more critical of how water has been managed in the West" That view has been echoed in the writings of Robert Kelley in Battling the Inland Sea (1989) and Donald Pisani in, among others, Water, Land, and Law in the West (1996) who, like Hundley, have emphasized California. In their opinion, the federal government has not done nearly enough to govern water; it has built massive dams and other infrastructure but has not used its power to settle questions of distribution, leaving them instead to a cacophony of local interests.

To a point they are right; Washington has seemed reluctant to confront the self-seeking demands of land and water entrepreneurs who would impose their values on nature

and society in the West. But, as I have argued in a number of works, the federal government has more often shared rather than opposed those values. Working together rather than in opposition, capital and bureaucracy have drastically reordered the arid region. They have shared a common logic, a broad plan of conquest, in the name of economic growth. They have achieved, as intended, an "empire" that today boasts forty million irrigated acres and sprawling metropolises. They have accumulated power as well, just as Powell feared they would. The most intriguing question for this historian is how long they will be able to hold on to that power or maintain their imposed order over a desert that can never really be conquered or evaded.

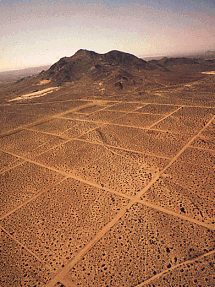

Unused subdivision laid out

in 1948 in California, 1978"civilization will continue

to face the challenge of how

to live successfully in

this difficult land"Whether culture or nature, society or aridity, proves dominant in the long term is an issue that can only be settled by scholars in the future. Most likely, neither force will win out absolutely and civilization will continue to face the challenge of how to live successfully in this difficult land.

Links to Online Resources

Illustration Credits

Works Cited

Comments & Questions

Donald Worster is the Hall Distinguished Professor of History at the University of Kansas. He earned a Ph.D. from Yale University in 1971 and has held fellowships from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the American Council of Learned Societies, and the Guggenheim Foundation. He is past president of the American Society for Environmental History. His books include Nature's Economy: A History of Ecological Ideas (1977/1994), Dust Bowl: The Southern Plains in the 1930s (1979), Rivers of Empire: Water, Aridity, and the Growth of the American West (1985), Under Western Skies: Nature and History in the American West (1992), The Wealth of Nature: Environmental History and the Ecological Imagination (1993), and A River Running West: The Life of John Wesley Powell (2000).

Address comments or questions to Professor Worster through TeacherServe "Comments and Questions."

| "Wilderness and American Identity" Essays |

| The Puritan Origins of the American Wilderness Movement | The Challenge of the Arid West | Rachel Carson and the Awakening of Environmental Consciousness Essay-Related Links |

TeacherServe Home Page

National Humanities Center

7 Alexander Drive, P.O. Box 12256

Research Triangle Park, North Carolina 27709

Phone: (919) 549-0661 Fax: (919) 990-8535

Revised: July 2001

nationalhumanitiescenter.org