The Challenge of the Arid West

Donald Worster, University of Kansas

©National Humanities Center

|

|

(part 2 of 4)

GUIDING STUDENT DISCUSSION

Like other aspects of the natural world, the visceral reality of aridity has become, for most students

today, an abstraction. Even in places like Phoenix or Cheyenne, they enjoy a seemingly endless supply

of water, and their food is always reliably there in the supermarket. So the first step is to get them

thinking about how earlier generations coped with searing drought, sudden, torrential floods, dry water

holes, the differences between spring and fall in river level, the hand digging of wells. Imagine with them

how Indians, and then whites, tried to solve the problem of quenching their thirst with only simple

technology.

|

| |

Denver Public Library  |

|

Denver Public Library  |

|

| |

Dog travois used by Native Americans

to transport water, 1870 (?) |

|

Irrigation ditch and white farmer

in Colorado, c. 1905 |

|

"Imagine with them

how Indians, and then whites, tried to solve the

problem of quenching their thirst with only simple

technology."

|

|

|

A bright student may raise the question whether aridity has meant the same thing to everybody or has

varied from culture to culture. Pat that student on the head and turn

|

|

Sod house

Nebraska, n.d.

| Wichita State University

|

"By such imported standards of judgment, nature in the West may appear very deficient."

|

|

|

|

the discussion to the ways in which

aridity is both an ecological fact of nature, measurable and objective, and a culturally defined condition.

We perceive nature according to the standards of "normality" with which we're familiar. The modern-day newcomer to Las Vegas may insist that a bluegrass lawn around his house is normal; he is no

different than the nineteenth-century pioneer

|

|

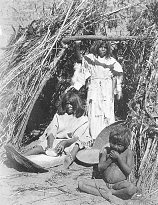

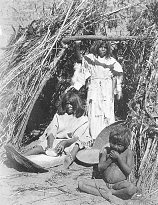

Paiute woman

grinding seeds, 1872  |

| | National Archives |

"But it was not

deficient . . . or even 'arid' in the eyes of the Paiutes who dwelt in the Great Basin"

|

|

|

who expected to transplant her milk cows, her fruit trees,

indeed her whole notion of what it meant to live on the land. By such imported standards of judgment,

nature in the West may appear very deficient. But it was not deficient in the eyes of a pronghorn. Nor

was it deficient or even "arid" in the eyes of the Paiutes who dwelt in the Great Basin; they learned how

to feed themselves on desert seeds, small mammals, and grasshoppers and even assumed that they lived

in the most blessed part of the earth! While all living things must maintain a water balance or die, most

people in history have consumed water, directly or indirectly, beyond their basic biological needs.

Encourage students to consider how culture enters the picture and begins to shape what we mean by

aridity, deserts, or scarcity.

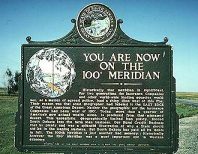

Ask your students what cultural attitudes Americans brought with them to the West in the nineteenth

century, and then how those attitudes have changed down to our own time. In the first place, they

generally came as farmers or grazers, bringing with them a culture based on domesticated plants and

animals that determined how they appraised the land and what they wanted from it. That is what Powell

had in mind when he talked about the significance of the hundredth meridian: it was a line that a society

based on agriculture could not cross without adjustment.

Get out a map and note the average rainfall

amounts west of Powell's line, and then ask how much water a cow or sheep, a corn or wheat crop

needs, and how they could survive in the West. Try to find grains or legumes—anywhere on earth—which can thrive on such low precipitation.

TeacherServe Home Page

National Humanities Center

7 Alexander Drive, P.O. Box 12256

Research Triangle Park, North Carolina 27709

Phone: (919) 549-0661 Fax: (919) 990-8535

Revised: July 2001

nationalhumanitiescenter.org |