(part 2 of 2)

|  |

|

| slideshow | image info

|

|

"all of these momentous changes were profoundly unsettling to ordinary men and women"

|

|

|

|

To prod them into thinking along these lines, you might talk a bit about the sweeping changes (and

uncertainties) overtaking the lives of most western Europeans in the early modern period (ca., 1400-1800).

It was during this era that the beginnings of modern capitalism—both the growth of trade and the

commercialization of agriculture—were yielding handsome profits for merchants and large landowners, but

creating inflation and unemployment that produced unprecedented misery for many more people. The rich

were getting richer, and the poor much poorer: growing numbers of unemployed people became vagrants,

beggars, and petty criminals. To add to the sense of disruption and disarray, the Protestant Reformation of

the sixteenth century had ruptured the unity of late medieval Christendom, spawning bloody religious wars

that led to lasting tensions between Catholics and Protestants. Finally, Europeans had "discovered" and

begun colonizing what was to them an entirely new and strange world in the Americas. All of these

momentous changes were profoundly unsettling to ordinary men and women, heightening their need for

social order, intellectual and moral certainty, and spiritual consolation.

|

|

| Library of Congress | enlarge image |

|

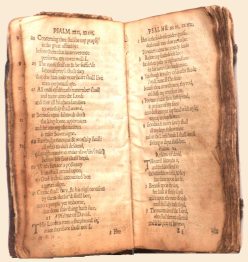

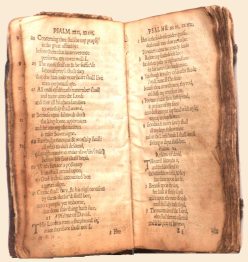

The Bay Psalm Book, printed in Boston, 1640: the first book printed in the British colonies.

|

|

|

|

For many, the doctrine of predestination answered these pressing inner needs. Its power to comfort

and reassure troubled souls arose from its wider message that, beyond preordaining the eternal fates of men and women, God had a plan for all of human history—that every event in the lives of individuals and nations somehow tended toward an ultimate triumph of good over evil, order over disorder, Christ over Satan. In other words, Calvin (and his many followers among groups like the Puritans) saw human history as an unfolding cosmic drama in which every person had a predestined role to play. True, men and women

had no free will, but they had the assurance that their existence—indeed, their every action—was MEANINGFUL and that their strivings and sufferings in the present would ultimately produce a future of perfect peace and security—a kind of heaven on earth.

That confidence made people like the Puritans anything but passive or despairing. On the contrary,

they were an extraordinarily energetic, activist lot, constantly striving to reshape both society and

government to accord with what they believed to be the will of God as set forth in the Bible. They strove,

too, to lead godly and disciplined lives—but not because they hoped that such righteous behavior would earn them salvation. Instead they believed that their very ability to master their evil inclinations provided some evidence that they ranked among the elect of saints. In other words, the Puritans did not regard

|

| capecodgravestones.com |  |

|

Gravestone of Phebe Gorham, d. 1775, Cape Cod, Massachusetts. Epitaph:

|

Henceforth my Soul in sweetest Union join

The two supports of human happiness,

Which some erroneous think can never meet,

True Taste of Life, and constant thought of Death

|

|

|

|

leading a

godly, moral life as the CAUSE of a person's salvation, but rather as an encouraging sign of the EFFECT of being chosen by God to enjoy eternal bliss in heaven. It was impossible, of course, to be entirely confident of one's eternal fate, but that edge of uncertainty only made believers redouble their efforts to purify their own lives and society as a whole. And nothing was more important to early modern men and women than gaining greater reassurance of salvation.

Historians Debate

|  |

|

| Huntington Library |

|

John Eliot, ca. date (unknown artist). Eliot a Puritan minister in 17th -c. Massachusetts, was known as the "Apostle of the Indians."

|

|

|

|

Few subjects in early modern history have received more attention from scholars than Puritanism,

and historians of early America have focused the most intense scrutiny on the Congregationalists of

colonial New England. The most profound modern interpreter of that Puritan culture is Perry Miller, whose

work first appeared in the middle decades of the twentieth century and whose influence endures to the

present with such works as The New England Mind (1929/1953) and Errand into the Wilderness (1956). Miller was the first scholar to appreciate the importance of Puritanism as a complex set of ideas, a

magisterial theology that set forth a rich, compelling depiction of the relationship between God and

humankind. In Miller's view, Puritanism was also a dynamic, protean, intellectual force, constantly adapting to keep pace with the rapidly shifting social conditions and cultural climate over the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries.

Many of the historians who followed Miller in the 1960s and 1970s concluded that the vitality and

integrity of Puritanism as a cultural force was sapped and finally spent by broader social and intellectual

challenges. In their view, the growth of commercial capitalism in New England and the spread of

"enlightened" learning had yielded, by the opening decades of the eighteenth century, a far more secular,

competitive, litigious, and materialistic society—one in which "Puritan" piety was rapidly being eroded by

"Yankee" worldliness. (The best treatment of this thesis is Richard Bushman, From Puritan to Yankee [1967].) But more recently, in the 1980s and 1990s, other scholars have argued that

Puritanism's influence held sway even among the cosmopolitan merchants of bustling New England

seaports well into the eighteenth century and that all inhabitants of the region as a whole long remained

steeped in Puritan values and spirituality. Indeed, they contend that the Puritan emphasis on social

hierarchy and communal obligation, as well as its ascetic piety and intolerance of competing faiths, actually

contained the force of capitalist expansion within New England and limited the extent to which the

participation in a market economy and the quest for profit could reshape social relations and values. (To

sample this revisionist scholarship, see Stephen Innes, Creating the Commonwealth [1996].)

|

| Library of Congress |

|

Puritan church with pulpit, pews, and, significantly, no altar. Old Ship Meeting House, Hingham, Mass., built in 1681.

|

|

|

|

While scholars continue to debate the strength of Puritanism among eighteenth-century New

Englanders, broader agreement has emerged about the region's religious culture during the seventeenth

century. The then "new" social historians of the 1970s were inclined toward the suspicion that the Puritan

doctrine being handed down from the pulpit may have mattered little to many ordinary New England lay

people. But subsequent research has now left little doubt that Puritan theology compelled the loyalties of

early New Englanders of all classes and that even the humblest farmers and fisherfolk were often well versed in the basic doctrines pertaining to predestination and conversion. What they heard from their

preachers, they both understood and generally accepted as the essence of true Christian faith.

Even so, both ordinary New Englanders—and their "betters," including college-educated clergymen—also lived in what one

historian has aptly called "worlds of wonder." These "wonders" include the belief in witches, the power of

Satan to assume visible form, and a variety of other preternatural phenomena that are still routinely

chronicled today in supermarket tabloids—the foretelling power of dreams and portents, strange prodigies,

"monstrous" births, and miraculous deliverances. To appreciate just how rich and bizarre this range of

beliefs was, check out the chapter on "wonders" in David Hall, World of Wonders, Days of Judgment (New York, 1989). It's a great way to enliven a dull hour—and a quick way to get some sense of the complexity of beliefs about the supernatural among early New Englanders of every rank and education.

But these remarks don't even begin to do full justice to the lively scholarship on New England

Puritanism that has evolved over the last half of the twentieth century. If you want to know more about

other topics, please read under Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries: Religion, Women, and the Family in Early America or Religion and the American Revolution.

Christine Leigh Heyrman was a Fellow at the National Humanities Center in 1986-87. She holds a Ph.D. from Yale University in American Studies and is currently Professor of History in the Department of History at the University of Delaware. Dr. Heyrman is the author of Commerce and Culture: The Maritime Communities of Colonial New England,

1690-1740 (1984), Southern Cross: The Beginning of the Bible Belt (1997), which won the Bancroft Prize in 1998, and Nation of Nations: A Narrative History of the Republic, with James West Davidson, William Gienapp, Mark Lytle, and Michael Stoff (3rd ed., 1997).

Address comments or questions to Professor Heyrman through TeacherServe "Comments and Questions."

Links to online resources

Illustration Credits

Related info in "Getting Back to You"

Comments and Questions