Roads, Highways, and Ecosystems

John Stilgoe, Harvard University

©National Humanities Center |

|

(part 2 of 6)

|

Sentinel Butte, North Dakota, 1915

| Library of Congress |

|

The first group to agitate for better roads, the League of American Wheelmen, grew out of the 1890s bicycle craze, and the second group evolved with railroad company support. Bicyclists adored paved roads, but away from cities found none. By 1900 the LAW had become the nation’s largest special-interest group, and it advocated paving roads with crushed stones. The macadamized road, named after its Scottish inventor, John Loudon MacAdam, had a multilayered surface of crushed stone: the largest stones, about the size of an adult human skull, at the bottom, then another layer about the size of an adult fist, then a top layer of stones no larger than can go into an adult mouth.

|

Prison inmates, 1928

| Florida State Archives |

"Macadamizing a country road meant backbreaking work in the days of horses, wagons, and picks and shovels"

|

|

|

|

Macadamizing a country road meant backbreaking work in the days of horses, wagons, and picks and shovels, and until the development of steam-powered stone crushers, many states set convicts to work smashing stones with sledgehammers. Convict labor sometimes moved outside prisons to the roads themselves, the men working under guard, and sometimes in the chains and manacles that led to the expression chain gang.

|

|

Isaac B. Potter,

The Gospel of Good Roads: A Letter to the American Farmer, 1891, title page

image enlargement

|

|

|

While no one proved much about the economics of convict labor, the LAW insisted that the macadamized roads benefited more people than just the bicyclists. Gradually, the LAW convinced farmers that a road fit for bicycles saved farmers time, trouble, and money. Between 1889 and 1900 it distributed about five million copies of its pamphlets on road improvement. The most famous of the pamphlets, The Gospel of Good Roads: A Letter to the American Farmer, appeared in 1891, and convinced many farmers that improved roads meant reduced transportation costs (fewer horses hauled the same tonnage), much time saved in traveling back and forth to town and to neighbors’, and far fewer damaged wagons and lamed horses. The LAW joined forces with farmers in a new lobbying group, the National League for Good Roads, and the new group soon convinced railroad companies to join.

|

1910

| Minnesota Historical Society |

"above all, a steam roller for

packing down the stones

impressed onlookers"

|

|

|

| Railroad companies quickly accepted the National League arguments and began sending

“Good Roads” trains to rural stations. At railroad company expense, men and machinery would build a mile or two

of macadamized road away from a railroad station into the country. Horse-drawn dump wagons and graders, but

above all, a steam roller for packing down the stones, impressed onlookers from the beginning.

|

|

|

Macadam road,

Florida, 1910

| Florida State Archives |

"But the new-surfaced roads

stunned everyone."

|

|

|

But the new surfaced roads stunned everyone. Farmers instantly realized that on a macadamized road their horses worked far less hard, and that indeed a two-horse team could pull a wagon needing a four- or six-horse team on ordinary dirt roads. A macadamized road drained well on rainy days and never turned to mud, and the steel wagon-wheel rims and steel shoes of the horses compacted the top layer of small stones into a hard, more or less even surface that stayed in

place wonderfully well. Farmers living along a macadamized road became more efficient and increased crop production, which meant more produce for the railroad companies to haul from rural stations

to cities. However unlikely the combination seemed at first, the LAW and the railroad industry soon convinced

the nation’s farmers that macadamized roads increased productivity and cut

transportation costs. Once used to the

roads, farmers and other rural and small-town short-distance travelers suddenly

disliked dirt roads as utterly old fashioned.

|

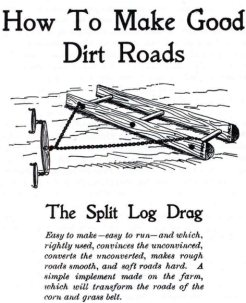

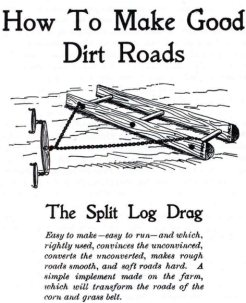

Road drag,

1910

| Harry Darius Ayer

Minnesota Historical Society

|

|

Henry Wallace,

"How to Make Good Dirt Roads," 1905

image enlargement

|

|

|

|

Where farmers could not afford macadamized roads, they began to drag them with crude devices made from split trees. Invented around 1904 by a Missouri farmer, D. Ward King, “the King road drag” was soon used by farmers everywhere in the United States to improve roads. Farmers working outside the Iowa town of Owasa even had a song to speed their work with the drag:

Dragging the roads, dragging the roads

Dragging the roads with the King road drag;

Hard as a bone, smooth as a hone,

The roads that lead into Owasa.

In many parts of the nation, the simple King road drag improved roads enough that farmers found macadamizing unnecessary.

Then, suddenly, technological change fractured the alliance of bicyclists, railroad companies, and farmers. Motor cars not only ruined macadamized roads but destroyed drag-smoothed roads too. Automobile tires ripped up the compacted surface of steam-rolled stones, making ruts that annoyed bicyclists and horse-driving farmers alike. The ruts channeled rainstorm water that eroded roads or trapped it in dangerous puddles that in winter froze into road-heaving chaos. But once automobiles operated reliably and at speeds up to fifteen miles an hour, town-to-town travel became possible over macadamized roads. By 1915 railroad companies noticed dramatic decreases in short-distance passenger ridership as more and more people abandoned buggies—and bicycles—for automobiles. An extraordinary transportation revolution was under way, and no one had a clear picture of what would happen even five years ahead.

But by 1925, seventeen million automobiles and other motor vehicles operated over twenty

thousand miles of concrete-paved roads and over hundreds of thousands of miles

of improved roads.

|

Putting in street pavement at Kerkhoven,

Minnesota, 1925

| Charles Lincoln Merryman

Minnesota Historical Society |

|

TeacherServe Home Page

National Humanities Center

7 Alexander Drive, P.O. Box 12256

Research Triangle Park, North Carolina 27709

Phone: (919) 549-0661 Fax: (919) 990-8535

Revised: July 2001

nationalhumanitiescenter.org |