History with Fire in Its Eye: An Introduction to

Fire in America

Stephen J. Pyne, Arizona State University

©National Humanities Center |

|

(part 3 of 3)

GUIDING STUDENT DISCUSSION

Most urban students—and most of us are urban (or suburban or exurban)—have little personal experience with fire, except in ceremonial contexts like campfires or fireplaces. One of the first lessons of childhood is "Don't touch the flame!" "Learn not to burn" is an educational mantra. Yet students must find some point of personal connection if they are to understand or even show interest in fire. They can then understand fire events and use those incidents, or patterns, to explain other themes more traditionally identified with the humanities.

There is hope. Fire is frequently in the news and on the Net. Something is always burning somewhere. And even in the built environment, nearly every room, building, or city block is designed with the threat of fire in mind. A few suggestions:

|

|

- Discover what students know or have experienced about fire—or might know and not realize.

- Where have they witnessed fire? What caused it? What does the incident mean?

- The students may know more than they realize. Consider certain fire ceremonies, of which vestiges remain. Halloween, May Day, Midsummer's Day, the Yule log—all were, in their origins, fire ceremonies. Why do they appear on the calendar when they do? What meaning was attributed to those fires?

|

- Examine the classroom for its measures against fire's threat—alarms, smoke detectors, sprinklers, exits, emergency power, panic doors, occupancy levels. Even in the built environment, is not fire shaping almost every room?

- Trawl the news for fire-related

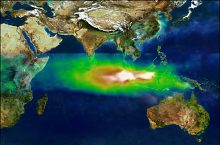

stories—landclearing fires in Indonesia and Brazil, wildfires in boreal Canada and Russia, swidden and pastoral burning in sub-Saharan Africa, efforts to introduce fire into American national parks, combustion as a source of greenhouse gases (see online resources). Each of these can become points of discussion about why fire exists, what forms it takes, and what cultural messages it contains. A good website to stay current is the Global Fire Monitoring Center in Freiburg, Germany.

- During fire season, track the daily situation reports from the National Interagency Fire Center, which are posted on the Web. What combination of natural, historical, and social conditions explains why fire is burning through forested suburbs along Colorado's Front Range? What accounts for the high-intensity fires in the ponderosa pine forests of the West? Why does Florida burn so often? Why is there so little fire in Vermont?

|

|

| SHS of Wisconsin | enlarge image |

|

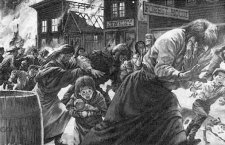

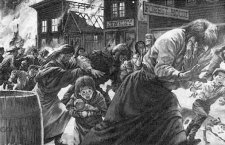

Illustration from The Great Peshtigo Fire

|

|

| - For some classes, primary

documents about fires might help frame a session. The Rev. Peter Pernin lived through the firestorm that incinerated Peshtigo, Wisconsin in 1871 (Chicago burned the same day). His account (full text) could trigger discussion about why fires clustered around frontier settlement, and how settlers perceived the conflagration.

| Other accounts exist that describe Indian burning, although these consist mostly of isolated passages. Usefully, John Wesley Powell's 1878 classic Report on the Lands of the Arid Region of the United States printed a map of Utah in which extensive burned areas are attributed to burning by indigenous peoples (although Powell argued that their displacement by white settlers aggravated the situation). |

|

| S. Pyne | enlarge image |

|

Powell's map of Utah, 1878, indicating burned areas (detail)

|

| desert |  | forest |

| irrigated cropland |

| burned land |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| USFS | enlarge image |

|

Forest destroyed by the hurricane-force winds and flames of the Big Blowup of 1910, Idaho

|

|

|

|

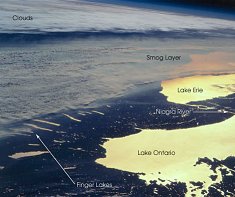

A number of case studies exist that describe fire behavior. The South Canyon fire investigation, for example, explains in accessible detail how that blowup developed and why it killed fifteen firefighters (full text). In fact, the behavior being analyzed concerns humans as much as fire. In this instance, a good link with the humanities exists in the form of Norman Maclean's meditation on the 1949 Mann Gulch fire in Montana, Young Men and Fire (excerpt). (The U.S. Forest Service report on the Mann Gulch fire is available online [full text].) That book, published in 1992, has provided an interpretive prism by which observers have understood contemporary wildfires, including the 1994 fire on Storm King Mountain. The power of Maclean's prose illustrates nicely how cultural processes such as literature can affect practices on the ground. Finally, one can study the Big Blowup of 1910 in Idaho, a firestorm that killed 78 firefighters, savaged three million acres, and literally incinerated several towns. The trauma of that event profoundly shaped America's national strategy toward wildland fire. It offers an excellent illustration of how nature and society collide, and how the humanities can illuminate what might seem to be a problem for natural science and technical bureaus. For a rousing account, see Pyne, Year of the Fires: The Story of the Great Fires of 1910 (2001) (excerpt).

SCHOLARS DEBATE

There is no field of fire studies, so there is no tradition of theses and counter-theses. There is almost nothing that tries to unravel the history and meaning of fire itself. The other Aristotelian "elements"—air, water, earth—have academic departments to study them. The only fire department at universities is the one that dispatches emergency vehicles when an alarm sounds.

Instead, scholars have examined fire through their own disciplinary lenses. Thus research follows the agendas of sponsoring institutions; scholars often disagree; there is not even a common corpus of shared questions. Even most science is restricted to public wildlands where the state has administrative responsibility. Really, it is remarkable that the general history of fire and humanity is so poorly known and that no coherent body of scholars is pursuing the topic.

To the extent that much debate exists, it concerns the two borders of anthropogenic fire—those it shares with natural fire and those with industrial fire. Lamentably, in this discussion, the humanities seem to be AWOL.

The first has spawned the most vigorous discussion in America. How much of those pre-European fires were started by nature and how much by American Indians? Everyone agrees that there is a lot less open fire today than a century ago and that the public wildlands are the worse for their exclusion. It seems important to decide whether nature alone should reinstate fire, or whether the missing fires came from humans and thus justify deliberate burning as a means of restitution. Scientists look to fire-scarred trees, forest structure, comparative historical photos, and sediment cores as evidence,

and generally dismiss the textual documentation of the humanities as anecdotal. Historians—those who bother—generally trust their reading of documents and consider the scientific database as too selective. They are liable, moreover, to point out that most of the world's landscapes are cultural creations and that fire ecologists have generally ignored those landscapes, even obvious ones like agriculture.

Curiously, the problem of industrial fire as a landscape force has not been systematically examined, save the issue of fossil-fuel combustion as a contributor of greenhouse gases. Yet the controlled combustion of fossil biomass is rewriting the Earth's landscapes wholesale. (Just think of automobiles and how they have refashioned scenes, for beginners.) Until the study of fire acquires a disciplinary standing, however, these questions are unlikely to become the theme of coherent discourse.

| J. G. Goldammer |

|

Stephen Pyne

|

Excerpt from Pyne's Fire on the Rim on his firefighting experience

|

|

|

|

So why did I become interested? That's easy to explain. A few days after I graduated from high school I took a job on the fire crew at Grand Canyon's North Rim. I returned for fifteen seasons, and then helped write fire plans at other parks for three summers more. Meanwhile I studied in the humanities, acquiring a Ph.D. in 1976. It finally occurred to me that I ought to apply the techniques of scholarship that I had learned to the subject that most enthralled me. I started what has evolved into a dozen books on fire, six of them organized into a suite—what I call Cycle of Fire—that attempts to survey the history of fire on Earth. When I began on the North Rim, we were called smokechasers. That's what I still do, chasing smokes, though with a pencil rather than a shovel.

Stephen J. Pyne was a Fellow at the National Humanities Center in 1979-1980 and will return to the Center in 2002-2003 to write a history of fire in Canada. He holds a Ph.D. from the University of Texas at Austin and is presently affiliated with the Biology and Society Program within the School of Life Sciences at Arizona State University. Among his many books are Fire on the Rim: A Firefighter's Season at the Grand Canyon (1989), How the Canyon Became Grand (1998), and Year of the Fires: The Story of the Great Fires of 1910 (2001).

His Cycle of Fire suite includes

| | Fire in America: A Cultural History of Wildland and Rural Fire (1982)

The Ice: A Journey to Antarctica (1986)

Burning Bush: A Fire History of Australia (1991)

World Fire: The Culture of Fire on Earth (1995)

Vestal Fire: An Environmental History, Told through Fire, of Europe and Europe's Encounter with the World (1997)

Fire: A Brief History (2001). |

Dr. Pyne's website at Arizona State University.

Address comments or questions to Professor Pyne through TeacherServe "Comments and Questions."

TeacherServe Home Page

National Humanities Center

7 Alexander Drive, P.O. Box 12256

Research Triangle Park, North Carolina 27709

Phone: (919) 549-0661 Fax: (919) 990-8535

Revised: October 2002

nationalhumanitiescenter.org |

Links to Online Resources

Illustration Credits

Excerpts & Reports

Comments & Questions