History with Fire in Its Eye: An Introduction to

Fire in America

Stephen J. Pyne, Arizona State University

©National Humanities Center |

|

(part 2 of 3)

The Long Burn

A thumbnail history of fire would go like this. More than 400 million years ago the atmosphere had enough oxygen, the lands enough plant matter, and skies enough lightning for them to converge and create combustion. Fire has thrived on Earth every since. It does so, however, in patterns called regimes, and these regimes are best understood as reflecting rhythms of wetting and drying. A place must be wet enough to grow combustible plants, and dry enough to ready them for burning. Some places experience this rhythm annually, some on longer scales of drought and deluge, some not at all. Individual fires are to fire regimes as individual storms are to climate. Still, biomass does not spontaneously combust; lightning must connect for ignition to result.

This narrative changed with early humans. Homo erectus could apparently maintain fire, and Homo sapiens make it, more or less at will. The Earth found a fire broker to link fuel with flame. Places that had the potential for fire but lacked regular ignition now had it. The outcome could be extraordinary, as, for example, with Madagascar and Australia, where change occurred on a continental scale.

Humanity found itself with a species monopoly that granted extraordinary power, but it would have to exercise that power according to social norms, values, perceptions, and institutions. Different people have created distinctive fire regimes, just as they have distinctive literatures and architecture. Thus fire became both natural and cultural, fit for analysis by both the natural sciences and the humanities. It became an agent of human change and an index of that change.

Library of Congress  Dance to restore an eclipsed moon, Kwakiutl Indians, Pacific Northwest, n.d. |

"Different people have created distinctive fire regimes, just as they have distinctive literatures and architecture."

|

B. Bertaut  Annual Cajun-tradition Christmas Eve bonfires, Louisiana, 2001 |

|

But immense limitations continued on humanity's firepower. Many places remained immune to ignition because they lacked the proper amount of dry fuel. The solution was to make fuel—cutting, burning, growing, stacking—which is, for fire history, the meaning of agriculture. Outside of floodplains, agriculture relied on a cycle of burning. In some cases, the farm moved through the landscape (as with classic slash-and-burn) or the landscape, in effect, revolved through a fixed plot of land (rotating fields). The practice of fallowing ensured that there would be sufficient fuel at the appropriate time. The fallowed land was not burned to remove its waste, but was grown in order to be burned. Thus agriculture expanded enormously the range and regimes of fire—bringing it to where it would not naturally have existed, reshaping its patterns into the discipline of fields and pastures.

Even so, anthropogenic fire could only burn what people or nature could produce. It remained within broad cycles of living biomass, the ancient rhythms of growth and decay. One could not take out more than one put back in.

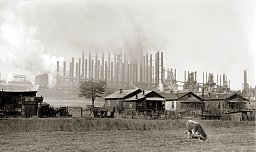

This restriction lifted, however, when people reached in to the geological past and began exploiting fossil biomass—the petroleum, coal, and natural gas that had lain buried for eons. Suddenly fire—controlled combustion in the hands of people—could burn outside its ancient ecological constraints. It could burn day and night, winter and summer, without regard to the living world. It could burn within special habitats like combustion chambers. There is fuel enough to power machines for hundreds of years. For fire history, these events define industrialization.

Industrial fire is remaking every conceivable landscape, just as aboriginal fire and agriculture fire had before it. The environmental consequences have been extraordinary because the process is both adding a new and gigantic form of combustion and removing older forms. Both trends matter because fire can be just as ecologically powerful removed as applied. Biotas adapt to fire regimes just as they do to patterns of rainfall. More rain, less rain, a change in rainfall seasons—these can stress ecosystems. So it is with fire. Industrial societies have remade some landscapes by charging them with the flow of industrial combustion and remade others by removing older practices of open burning.

Nature Conservancy  "Remade landscapes": Fire removed.

Longleaf pine forest, Florida, 1995. Lack of burning can result in thick understory which threatens the forest ecosystem.

Photo: after burning.

|

"fire can be just as ecologically powerful removed as applied"

|

Alex S. MacLean/Landslides  "Remade landscapes": Fire applied.

New Jersey suburb, n.d. Combustion now flows along roads and indirectly through powerlines, supporting a landscape for which open flame is dangerous.

|

|

The human manipulation of fire has been complex. In some ways it resembles a simple tool. Flame sits at the end of a torch like an axe-head at the end of a handle. In other ways, it better approximates a process of domestication. People must tend a fire—birth it, feed it, propagate it, train it, as they would a sheep dog or milch cow. The tamed fire sustains, and is sustained by, a larger domesticated landscape. Yet, again, anthropogenic fire resembles a captive ecological process, something that people can start and stop and shape but which behaves largely as its quasi-wild context allows it to freely burn. Managing such fires is akin to training a grizzly bear to dance.

Industrialization has affected these variants of controlled fire differently. It is relatively simple to substitute one fire tool for another—to replace candles with light bulbs, and hearths with electric ovens. It is less easy to substitute for the domesticated flame on the landscape. Field fires behave according to the combustibles that feed them, and they do their ecological work according to their setting. Substituting for them is like substituting a tractor for a plow horse, and hence for the fields that grow the fodder for the horse and the barn that houses it, and so on. The exchange ripples beyond a simple replacement of one mechanical tool for another. Yet industrial fire is pushing such transformations through. Most spectacularly, it is eliminating the need for fallowing. Fire was a biotic catalyst that made agriculture possible beyond floodplains. But fire requires fuel, and fallow—the rank growth that flourished on abandoned fields—was the fuel that made fire possible and helped discipline it into the rhythms of farming and herding. Industrial agriculture, however, appeals to fossil fallow—fossil biomass that powers tractors, supplies artificial fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides, and overall finds replacements for the fertilizing and fumigation previously done by open fire. There is, however, no known surrogate for fire as an ecological process.

Fire at the Millennium

A fire map of the United States today would be a palimpsest of the three great fires of Earth:

- natural fire, primarily caused by lightning

- anthropogenic fire, manmade fire practices that rely on living biomass, such as burning trees to clear land and stimulate pasture

- industrial fire, those stoked by fossil fuels such as coal and petroleum, i.e., nonliving biomass.

Compared to the past, such a map would show a massive loss of open flame. Where people live most densely—in cities—fire is rare and considered intrinsically dangerous. Elsewhere, it exists largely as wildfire, and that on public wildlands. What has most vanished is the ancient realm of controlled burning. It flourishes most vigorously today in places of aggressive landclearing.

Several problems dominate the contemporary discourse about American fire:

| |

(1) the role of fire in wilderness and nature reserves

(2) the increased mixing of wildlands and cities

(3) the relative merits of fire control and controlled fire

(4) the status of burning in a context of global change.

|

|

|

(1) The role of fire in wilderness and nature reserves. Many such sites (especially those in the American West) experience regular burning from lightning. These are natural events and should, it would seem, be tolerated, even encouraged. But how to reinstate "natural" fire has proved knotty, costly, and ironic. It has happened in a few places, notably along the Sierra Nevada. The scheme underwent a colossal collapse during the Yellowstone National Park fires of 1988. What to do with such fires is very much a matter of cultural choice. |

|

|

(2) The increased mixing of wildlands and cities. In many places urban fragments are flung into quasi-wild landscapes that are prone to burn. In other places abandoned agricultural lands are regrowing to woody thickets, again abutting houses. A gross description is that the once-rural landscape is being recolonized by urban (or suburban or exurban) peoples according to values and an economy they derive from elsewhere. If fire is at all possible, this mixture has proved volatile and unstable. Almost annually more and more houses fall to flame. This is a dumb problem to have because technical solutions exist such as zoning, landscaping, and incombustible roofs. |

|

|

(3) The relative merits of fire control and controlled fire. As a solitary technique, fire suppression has failed, so the argument has developed that we must retool to start fires instead. We must light fires because we can no longer assume we can fight them. But this misstates the issue. The choice is not one or the other, but the proper proportions of each as tested site by site. Nature does not set those proportions, people do. And we do it according to a confusing welter of values, choices, accidents, institutions, knowledge, perceptions, and misinformation for which the humanities are aptly equipped to explain and advise. The reintroduction of fire will demand suitable habitats, which is to say, the issues are not simply about kindling fires but about land use, and about how we see ourselves in relation to particular places. |

|

|

(4) The status of burning in a context of global change. Global warming, in particular, is a question of combustion. Like human populations undergoing industrialization, the population of fires tends to swell up alarmingly as new combustion sources appear and old practices persist. Eventually the population shrinks as the old ways collapse. But how to reconcile the continued need for some open fire within a planet temporarily overcharged with combustion is a tough call. It will force us to choose from among environmental values, for example, between biodiversity and carbon sequestration. Allowing forests to overgrow into woody tangles can stockpile carbon, but will likely bury the biotic variety of the landscape under a pavement of needles and woody litter. Conversely, breaking open such groves may enhance biodiversity but at a cost of liberated carbon. |

TeacherServe Home Page

National Humanities Center

7 Alexander Drive, P.O. Box 12256

Research Triangle Park, North Carolina 27709

Phone: (919) 549-0661 Fax: (919) 990-8535

Revised: October 2002

nationalhumanitiescenter.org |