The New Negro and the Black Image: From Booker T. Washington to Alain Locke

A longer version of this article under the title “The Trope of a New Negro and the Reconstruction of the Image of the Black” appeared in Representations, No. 24, Special Issue: America Reconstructed, 1840-1940 (Autumn, 1988). Reprinted by permission of the author.

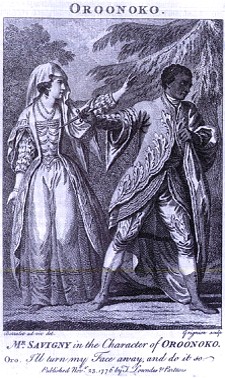

A 1776 illustration of the climactic scene in a dramatization of Oroonoko. |

|

The “New Negro,” of course, was only a metaphor. . . . [T]he trope itself . . . [combines] . . . a concern with time, antecedents, and heritage, on the one hand, with a concern for a cleared space, the public face of the race, on the other. . . . [It asserts a] . . . self-willed beginning [whose] . . . “success” depends fundamentally upon self-negation, a turning away from the “Old Negro” and the labyrinthine memory of black enslavement . . . toward the . . . “New Negro,” an irresistible, spontaneously generated black and sufficient self. . . . It is a bold and audacious act of language, signifying the will to power, to dare to recreate a race by renaming it, despite the dubiousness of the venture.

The New Negro and the Quest for Respectability: 1895 to World War I

Let us trace the history of the idea of the New Negro from 1895. An editorial in the Cleveland Gazette, celebrating the passing of the New York Civil Rights Law, spoke of “a class of colored people, the ‘New Negro,’ . . . who have arisen since the war, with education, refinement, and money.” In marked contrast with their enslaved or disenfranchised ancestors, these New Negroes demanded that their rights as citizens be vouchsafed by law. Significantly, these New Negroes were to be recognized by their “education, refinement, and money,” with property rights strongly implied as the hallmark of those who may demand their political rights. “Property,” in this sense, is only one of a list of “properties” demanded of this New Negro. “Education” and “refinement”—to speak properly was to be proper—would ensure one’s rights, along with the security of property. These terms come to bear, curiously, upon subsequent definitions. J. W. E. Bowen, in “An Appeal to the King” later that same year, again defined the New Negro, but here in terms only of racial “consciousness” and its relation to “civilization”: “the consciousness of a racial personality under the blaze of a new civilization.” Bowen’s “New Negro” leads directly to the [Harlem or New Negro] Renaissance, for it was above all through literature that both “a racial personality” and “the blaze of a new civilization” would manifest themselves. Bowen’s “New Negro” would create a universal racial art.

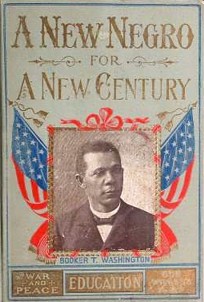

[The New Negro was also on the mind of Booker T. Washington. In 1900 he set out to define just who and what the New Negro was in] an elaborately constructed compendium of excerpted black histories, slave narratives, journalism, biographical sketches, and extended defenses of the combat performances of black soldiers from the American Revolution . . . to the Spanish-American War. [Titled A New Negro for a New Century: An Accurate and Up-to-Date Record of the Upward Struggles of the Negro Race, it]

|

|

And craft it Washington and his fellow editors attempted to do. The whole of A New Negro, some 428 pages and 60 portraits, reads now as a complex, if bulky, sign of both the individual achievements of black men and women as abolitionists, soldiers, and artists, and of the twentieth century’s “New Negroes,” the “progressive” classes of the race, who were forming numerous self-help institutions, such as “Colored Women’s Clubs,” key indicators of the race’s ”capacity” for “elevation.” . . . “Capacity” designated physical cranial measurements, but it quickly became the metaphor for the measure of the potential of human intelligence. The following lines from Frances Allen Watkins Harper, quoted in Mrs. Booker T. Washington’s essay on the “Club Movement Among Negro Women” in J. L. Nichols and William H. Crogman’s 1920 edition of The New Progress of a Race, indicate these origins clearly:

There is light beyond the darkness,

Joy beyond the present pain;

There is hope in God’s great justice

And the Negro’s rising brain.

A New Negro’s use of the keyword progressive dozens of times relates directly to an idea of progress through perfectibility. Booker T. Washington’s New Negro . . . stood . . . head and shoulders above the ex-slave black person, freed now for only thirty-five years. As the introduction postures:

This book has been rightly named A New Negro for a New Century. The negro of today is in every phase of life far advanced over the negro of thirty years ago. In the following pages the progressive life of the Afro-American people has been written in the light of achievements that will be surprising to people who are ignorant of the enlarging life of these remarkable people.

Of this anthology’s eighteen chapters, no less than seven are histories of black involvement in American wars, while six chapters “unmask” slavery. . . . Two chapters treat the “Club Movement Among Colored Women,” and one charts the educational progress of the race. Booker T. Washington’s portrait forms the frontispiece of the volume, while Mrs. Washington’s portrait concludes the book, thus standing as framing symbols of the idea of progress. Between this handsome pair are portraits of military figures . . . creative writers such as Paul Laurence Dunbar, T. Thomas Fortune, Charles Chesnutt, and Frederick Douglass; scholars, including . . . ; W. E. B. Du Bois and notable women such as . . . Mary Church Terrell . . . all of whom appear to be very “progressive” indeed.

Charles E. Young. From A New Negro for a New Century, 1900. |

Mary Church Terrell. From A New Negro for a New Century, 1900. |

The anthology’s apparent militaristic emphasis seems intent upon refuting claims made by Theodore Roosevelt in Scribner’s Magazine

in 1899 of the inherent racial weaknesses that would prevent black officers from commanding effectively, thus making mandatory, in subsequent wars, their command by white officers. Almost the whole of Sgt. Presley Holliday’s rebuttal, printed initially in the New York Age in 1899, appears in A New Negro, along with the histories of black valor in every American war. The tone of these essays is fairly represented by Holliday’s claim that black soldiers in the Civil War “turned the tide of war against slavery and the Rebellion, in favor of freedom and the Union.” To have fought nobly, clearly, was held to be a legitimate argument for full citizenship rights.

Despite an unprecedented emphasis upon black histories written by black historians, however, the New Negro’s relation to the past of the Old Negro is a problematical one. “Let us smother all the wrongs we have endured,” urges one essayist; “Let us forget the past.” This aspect of “the past” is not only forgotten in A New Negro, it is buried beneath all of the faintly smiling bourgeois countenances of the New Negroes awaiting only the new century to escape the recollection of enslavement. Fannie Barrier Williams’s essay on the “Club Movement Among Colored Women” is pertinent evidence here of an urge to displace racial heritage with an ideal of sexual bonding. “To feel that you are something better than a slave, or a descendant of an ex-slave,” she writes, “to feel that you are a unit in the womanhood of a great nation and a great civilization, is the beginning of self-respect and the respect of your race.” It is this direct relationship between the self and the race, between the part and the whole that is the unspoken premise of A New Negro. As much as transforming a white racist image of the black, then, A New Negro’s intention was to restructure the race’s image of itself. As Williams puts this necessity, “The consciousness of being fully free has not yet come to the great mass of the colored women in this country,” in part because ”the emancipation of the mind and spirit of the race could not be accomplished by legislation.” This call to “progress” and “respectability,” therefore, was meant to marshal the masses of the race into the regiments of the New Negroes who, of course, would command them. And if “Zip Coon,” “Sambo,” and “Mammy” were thought to be the stereotyped figments of racist minds, there was just enough lingering doubt about their capacities for progress for Washington and his cohorts to structure a manifesto directed as much at them as at sensitive, intelligent, and wealthy whites.

| |||||||||||

". . . a home making girl, is Gussie." |

|

Fannie Williams, writing . . . in 1902 . . . places the black woman at the center of the New Negro’s philosophy of self-respect. “The Negro woman’s club of today,” she maintains, “represents the New Negro with new powers of self-help.” Two years later, John H. Adams, Jr. in a Voice of the Negro essay called “A Study of the Features of the New Negro Woman,” concurred with Williams’s assessment of the central role of the Afro-American woman in the New Negro movement, and even went so far as to reproduce images of seven ideal New Negro women so that other women might pattern themselves after the prototype. One such photograph bears the following caption:

An admirer of Fine Art, a performer on the violin and the piano, a sweet singer, a writer mostly given to essays, a lover of good books, and a home making girl, is Gussie.

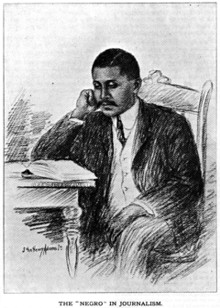

[T]wo months later Adams published the male response to his earlier essay. “The New Negro Man” appeared in the October 1904 number of the Voice of the Negro. Again, Adams is eager to chart the unpainted features of this New Negro. How does he describe him?

A new Negro man. From Voice of the Negro. |

|

Here is the real new Negro man. Tall, erect, commanding, with a face as strong and expressive as Angelo’s Moses and yet every whit as pleasing and handsome as Reuben’s favorite model. There is that penetrative eye about which Charles Lamb wrote with such deep admiration, that broad forehead and firm chin. . . . Such is the new Negro man, and he who finds the real man in the hope of deriving all the benefits to be got by acquaintance and contact does not run upon him by mere chance, but must go over the paths of some kind of biograph, until he gets a reasonable understanding of what it actually costs of human effort to be a man and at the same time a Negro.

As he had done in his essay on the New Negro woman, Adams prints seven portraits of the New Negro man, so that all might be able to recognize him.

What is of importance here is Adams’s stress upon the ”features” of this “new” Negro, drawing a correlation between the specific characteristics of the individuals depicted and the larger character of the race. Why is this so important? Precisely because the features of the race—its collective mouth shape and lip size, the shape of its head (which especially concerned phrenologists at the turn of the century), its black skin color, its kinky hair—had been caricatured and stereotyped so severely in popular American art that black intellectuals seemed to feel that nothing less than a full facelift and a complete break with the enslaved past could ameliorate the social conditions of the modern black person. While this concern with features would imply a visual or facial priority of concern, it was, rather, the precise structure and resonance of the black voice by which the very face of the race would be known and fundamentally reconstructed. Both to contain and to develop this black voice, a virtual literary renaissance was called for.

We see this impulse clearly in an essay printed in the A.M.E. [African Methodist Episcopal] Church Review in 1904. Incredibly, it is entitled “The New Negro Literary Movement,” which many have long assumed to be a phrase first introduced into black letters in the twenties. Citing the minutes of a literary club meeting of 1892, W. H. A. Moore quotes Anna J. Cooper (author of A Voice from the South, 1892) as demanding that “we must begin to give the character of beauty and power to the literary utterance of the race.” This urge, Moore continues, finally assumed a form in the writings of Dunbar, Chesnutt, Du Bois, and others, which taken together constitute a literary movement, a movement of New Negro voices that could recreate the received stereotypic figure of the black as Sambo. The metaphor of voice appears in Moore’s first sentences:

The New Negro Literary Movement is not the note of a reawakening, it is a halting, stammering voice touched with sadness and the pathos of yearning. Unlike the Celtic revival it is not a potent influence in the literature of to-day; neither is it the spirit of an endeavor to recover the song that is lost or the motive of an aspiration to reclaim the soul-love that is dead. Somehow it can not be measured by the standard of great achievement; and yet it possesses an air of distinction and speaks in the language of promise. It is the culminating expression of a heart growth the most strange and attractive in American life. To most of us it is as oddly familiar as though it breathed and spoke in the jungle of its forebearers.

In this new Negro voice, Moore concludes, a voice epitomized by Du Bois’s Souls of Black Folk, “We are going a long way in the direction of reaching a true understanding of the highest precept and purpose of the final democracy.”

What a curious phrase, ”the final democracy”! The final democracy could be realized only with the registering of the cadences of the black literary voice. This idea has such a long and intricate history in black letters that one could write a book about it. Suffice it to say here that W. H. A. Moore received it from writers such as E. Fortune, Jr., who in 1883 published an essay on ”The Importance of Literature: Its Influence on the Progress of Nations,” and found these ideas

echoed in essays such as a 1905 New York Age editorial entitled “Dearth of Afro-American Writers,” in which T. Thomas Fortune argued that “the capacity of a race is largely measured by the achievements of its writers, in whom its natural vigor and perspicuity of intellect, its highest moral revelations and its most delicate and beautiful emotions should reach consummation.” These statements are only two of many more. A New Negro would signify his presence in the arts, and it was this impulse that lead, of course, to the New Negro Renaissance of the twenties.

From Politics to Art: The New Negro from 1919 to 1925

[The New Negro], this black and racial self, as we define it here, does not exist as an entity or group of entities but ”only” as a coded system of signs, complete with masks and mythology. At least since its usages after 1895, the name has implied a tension between strictly political concerns and strictly artistic concerns. Alain Locke’s appropriation of the name in 1925 for his literary movement represents a measured co-opting of the term from its fairly radical political connotations, as defined in [African American publications like] the Messenger, the Crusader, the Kansas City Call, and the Chicago Whip, in bold essays and editorials printed during the post-World War I race riots in which Afro-Americans rather ably defended themselves from fascist mob aggression. Indeed, this tension between definitions is readily gleaned in the drastic difference between the “Old Crowd Negro-New Crowd Negro” cartoon, printed in the Messenger of 1919, and that drawing of “The New Negro,” done by Allan R. Freelon, which serves as the frontispiece to the 1928 number of the Carolina Magazine, heavily influenced by Alain Locke, that was devoted to the ”New Negro” and his writings.

|

[+] |

[+] |

|

"Following the Advice of the 'Old Crowd' Negro." Messenger, 1919. |

"The 'New Crowd Negro' Making America Safe for Himself." Messenger, 1919. |

|

[+] |

The New Negro by Allan R. Freelon. |

Locke’s antecedents are most certainly the “Old Crowd Negroes.” By 1928, the apparent, radical self-defense of the Messenger’s “New Crowd Negroes” has turned in upon itself in Freelon’s drawing: the two lynched figures in the lower left of the drawing are the ironic echoes of the “New Crowd Negroes.” The white mob fleeing the “New Negro’s” firing guns are also echoed ironically in the three white crosses on the hill, perhaps too ambiguously connotative of Calvary and the Klan, especially in such proximity to the lynched black bodies. In Freelon’s drawing, the nude and supple black female, in a posture of arrested motion, is silhouetted against what is meant to be a ritual mask of African descent, complete with cowrie shells. The whole is framed by a transcending rainbow, against the midnight background of the cosmos. In less than ten years, the figure of the “New Negro” has undergone changes of the profoundest sort. The two poles of this apparently drastic transformation, however, are present in even the earliest uses of the phrase, and its sheer resonating . . . force can be gleaned somewhat from the fact that Alain Locke’s and others’ postwar literatures saw fit to graft, onto its postwar connotations of aggressive self-defense, the mythological and primitivistic defense of the racial self that was the basis of the literary movement which we call the New Negro, or Harlem, Renaissance.

We have come a remarkably long way from Booker T. Washington’s image of the New Negro at the turn of the century. . . . [T]he militancy of the . . . [post World War I] figure of the New Negro was both too potent and too problematical to predominate within the black intelligentsia. In 1925, Alain Locke edited a special number of Survey Graphic entitled “Harlem: Mecca of the New Negro,” which served both to codify and to launch a second New Negro literary movement. But Locke’s New Negro served even more than this: it transformed the militancy associated with the trope and translated this into an apolitical movement of the arts. Locke’s New Negro was a poet, and it would be in the sublimity of the fine arts, and not in the political sphere of action or protest poetry, that white America (they thought) would at last embrace the Negro of 1925, a Negro ahistorical, a Negro who was “just like” every other American, a Negro more deserving than the Old Negro because he had been reconstructed as an entity somehow “new.”

In response to a seemingly rigid and fixed set of racist representations of the black as the ultimate negated ”Other”—as all that white culture feared about its “nether” side—black writers attempted to rewrite the received text of themselves. Blacks, well before 1925, were an “already read text,” as [critic] Barbara Johnson has defined a stereotype. Locke and his followers, by appropriating the trope of the New Negro from the radical black socialists then supplanting that content with their own, not only sought to rewrite the black term, they also sought to rewrite the (white) texts of themselves. If the New Negroes of the Harlem Renaissances sought to erase their received racist image in the Western imagination, they also erased their racial selves, imitating those they least resembled in demonstrating the full intellectual potential of the black mind.

Despite its stated premises, the New Negro movement was indeed quite polemical and propagandistic, both within the black community and outside of it. Claiming to be above and beyond protest and politics, it sought nothing less than to reconstruct the very idea of who and what a Negro was or could be. Claiming that the isolated, cultured, upper-class part stood for the potential of the larger black whole, it sought to imitate forms of Western poetry, “translating,” as it was put, the art of the untutored folk into a “higher,” standard English mode of expression, more compatible with the Western tradition. Claiming that it had realized an unprecedented level of Negro self-expression, it created a body of literature that even the most optimistic among us find wanting when compared to the blues and jazz compositions epitomized by Bessie Smith and the young Duke Ellington, two brilliant artists who were not often invited to the New Negro salons. It was not the literature of this period that realized a profound contribution to art; rather, it was the black creators of the classic blues and jazz whose creative works, subsidized by the black working class, defined a new era in the history of Western music. . . .

Guiding Student Discussion

Tracing the evolution of the trope of the New Negro from 1895 to 1925 gives teachers the opportunity to do at least two important things: first, to introduce students to the long tradition of African American efforts to recast the black image, and second, to explore the modulated political tenor of the Harlem Renaissance.

As we have seen, African American intellectuals have sought to reconstruct the black image for two reasons: first, to refute racist stereotypes and second, to instruct blacks themselves on what they—the intellectual leaders—took to be the proper way for blacks to advance, individually and collectively, when they found themselves in new circumstances. In 1895 the new circumstance was freedom; in 1925 it was the escape from the South and the aggregation of blacks in the cities of the North.

In the classroom you can begin your discussion of the New Negro and the remaking of the black image by considering Booker T. Washington in a new light. Students probably know him chiefly as an educator through his work with the Tuskegee Institute and as an advocate for black economic advancement and racial accommodation by virtue of his Atlanta Exposition Address. Presenting him as the editor of A New Negro for a New Century introduces him in a different role, that of image maker. To prepare your students to see him in this role, ask them to describe the image of the black worker he creates in his famous Atlanta address. What stereotype is he combating there? Then have your students analyze a selection of portraits from A New Negro. Once you have pointed out that they reflect the standard portrait style of the day, ask why it was significant for both blacks and whites that African Americans be depicted that way at that time. For what audiences were the portraits intended—black, white, rural, urban, Northern, Southern? What would they say to different viewers? What values do the portraits illustrate? What goals were Washington and his fellow editors seeking to achieve with the publication of A New Negro?

Washington was not the only African American to use visual images to combat racist stereotypes in late nineteenth-century America. In 1893 artist Henry Ossawa Tanner painted The Banjo Player. Displayed at the Cotton States Exposition in 1895, the same event at which Booker T. Washington delivered his Atlanta Compromise speech, it transforms the stereotype of the banjo-playing Sambo into an image of dignity, antecedents, and heritage. The Banjo Player and some examples of its racist antecedents are available in the National Humanities Center’s online anthology "The Making of African American Identity: Vol. II, 1865-1917." (To facilitate discussion about this painting or any visual image, you might want to use the analytical method provided by the National Humanities Center in its online anthologies.) Ask your students to compare Tanner’s approach to combating stereotypes with Washington’s. Which is more effective? Why? How, if at all, does The Banjo Player embody the values of Washington’s New Negro of 1900, of Locke’s New Negro of 1925?

In 1900, the same year in which A New Negro appeared, W. E. B. Du Bois compiled two albums of photographs entitled “Types of American Negroes, Georgia, U.S.A.” for the American Negro Pavilion at the Paris Exposition. These albums are available "The Making of African America Identity: Vol. II, 1865-1917." Like A New Negro, the Du Bois albums feature many portraits of members of the black elite, but they also include images of working people and group photos plus images of buildings, towns, and landscapes. Select a representative sample of images from Washington and Du Bois, and ask your students to compare and contrast them. What difference, if any, does it make that the Du Bois albums were intended for a foreign audience? How do Washington’s portraits depict black life in late nineteenth century America? How do the Du Bois albums? Which collection offers the most accurate portrayal? To what extent, if at all, do the Du Bois images capture the spirit of Washington’s “New Negro” of 1900? How does history figure into each collection? Which collection is more effective in refuting racist stereotypes? Which makes the better case for racial progress?

Of course, the deployment of black-created visual images to combat racist stereotypes continued through the twentieth century, as is evidenced by the work of African American artists Joe Overstreet and Betye Saar. Both took on the image of the mammy, specifically her incarnation as Aunt Jemima. You can introduce your students to their powerfully witty work and compare it profitably to Tanner’s The Banjo Player through the National Humanities Center’s online anthology "The Making of African American Identity: Vol. III, 1917-1968."

As noted above, in its usage after 1895, the trope of the New Negro existed within a continuum defined by the political on one side and the artistic on the other. Immediately after World War I, it gravitated toward the political, but by 1925 Alain Locke had pulled it in the direction of the artistic. The political-artistic tension exhibited in the evolution of the New Negro trope reflects a larger debate about the role of African American literature in general. Thus exploring the development of the trope allows you to introduce this issue to your students. In the antebellum era black writing was driven by abolitionist zeal, and in the years after the Civil War it served what the writer Charles Chesnutt called ”the high holy purpose” of advancing the recognition and equality of the race. With the advent of the New Negro Movement of the 1920s critics asserted that black writing should be free to abandon its explicit social and political purposes in favor of more aesthetic goals. This debate was conducted mainly by W. E. B. Du Bois, who argued that ”All art is propaganda,” and Alain Locke, who argued that ”propaganda perpetuates the position of group inferiority.” You will find the pertinent texts with discussion question in "The Making of African American Identity, Vol. III, 1917-1968."

To explore the modulated politics of the New Negro movement of the 1920s, you might discuss with your students the Old Negro-New Negro cartoons and the Alan Freelon illustration presented above. How do political concerns enter the Freelon drawing? What does the illustration say about political action? According to Freelon, what is the proper role of black self-expression?

You might also examine protest poetry written by Harlem Renaissance writers. "The Making of African American Identity, Vol. III, 1917-1968" offers examples by Claude McKay, Gwendolyn B. Bennett, Sterling A. Brown, Countee Cullen, and Langston Hughes. How does the spirit of their poetry compare with the spirit of the Old Negro-New Negro cartoons of 1919? To what extent do their poems confirm or refute the assertion that the New Negro movement of the 1920s sought the acceptance of white America in the sublimity of the fine arts and not in the political sphere of action or protest poetry?

NHC Home | TeacherServe | Divining America | Nature Transformed | Freedom’s Story

About Us | Site Guide | Contact | Search